Browse the Architizer Jobs Board and apply for architecture and design positions at some of the world’s best firms. Click here to sign up for our Jobs Newsletter.

Frank Lloyd Wright is the most exhibited architect in the history of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The most recent blockbuster exhibition focusing on the famed American architect, “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” was a 400-object showcase unveiling the detailed drawings, models and plans of the great 20th-century architect. The show attracted thousands of visitors from the architecture profession and far beyond. So, why is this particular architect still so relevant? Why are so many people still fascinated by his work over half a century since his death?

The fact that many of his buildings have perpetual waitlists to visit them indicates the level of admiration and cultural curiosity his work has continued to receive since his passing. This, in turn, poses another question: If everyone knows him so well, and MoMA itself has exhibited his work so much in the past (Wright was even part of the museum’s inaugural architectural exhibition in 1932), what is there new to say about the world-renowned architect?

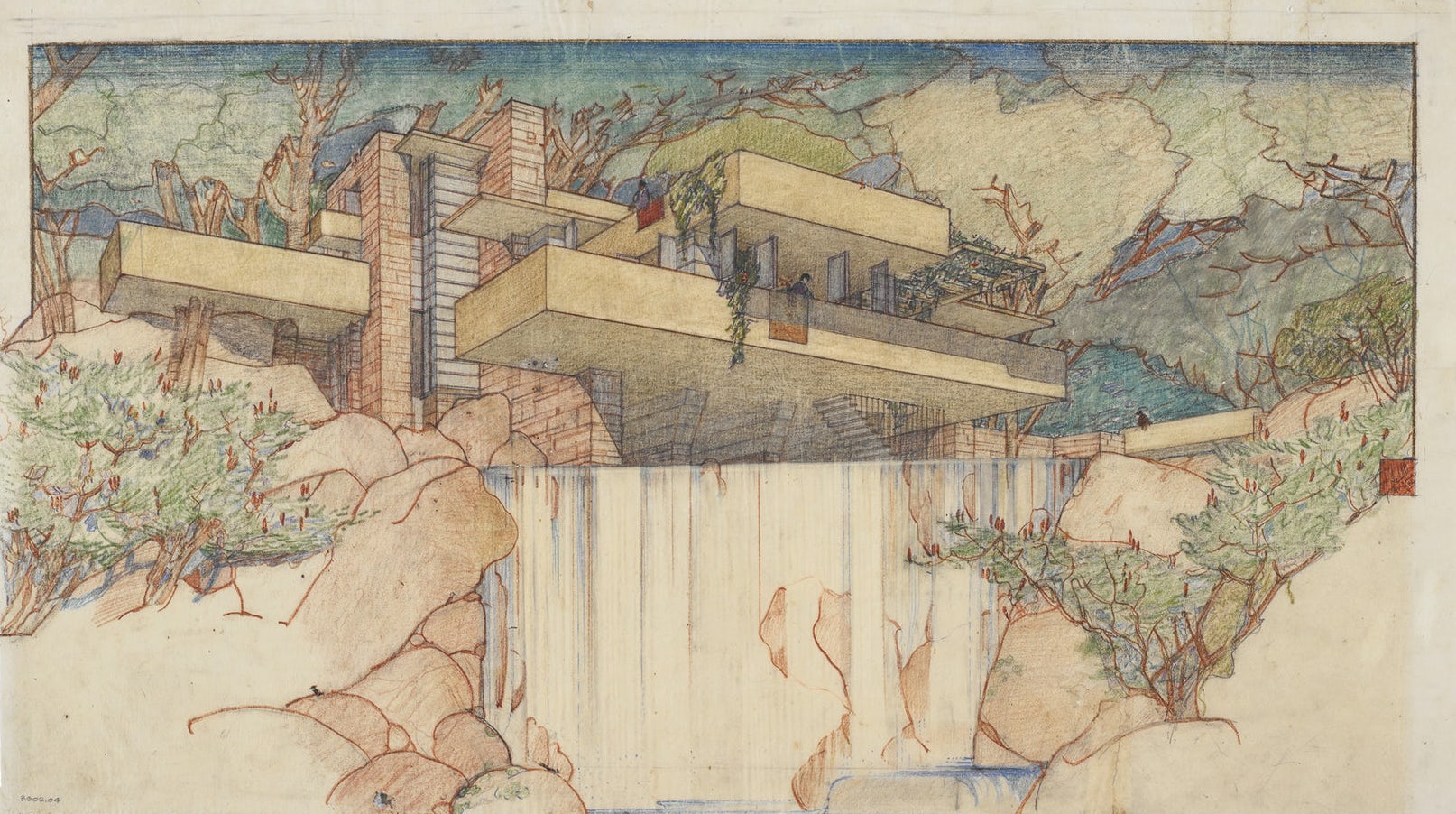

Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania. 1934 – 37. Perspective from the south. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 15 3/8 × 25 1/4” (39.1 × 64.1 cm). Image courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

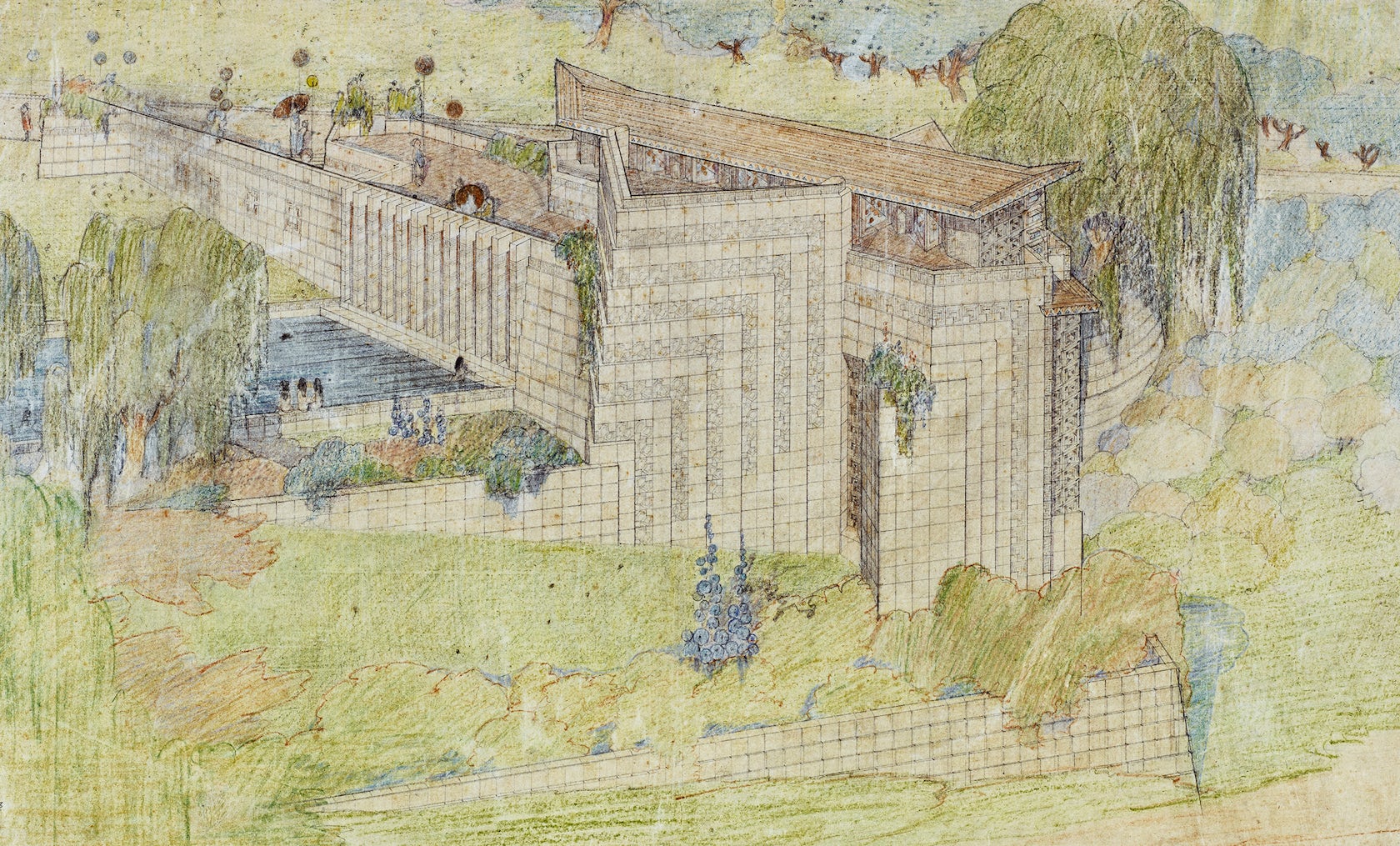

Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois. 1905 – 08. Perspective from the west. Watercolor and ink on paper, 12 × 25 1/8” (30.5 × 63.8 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

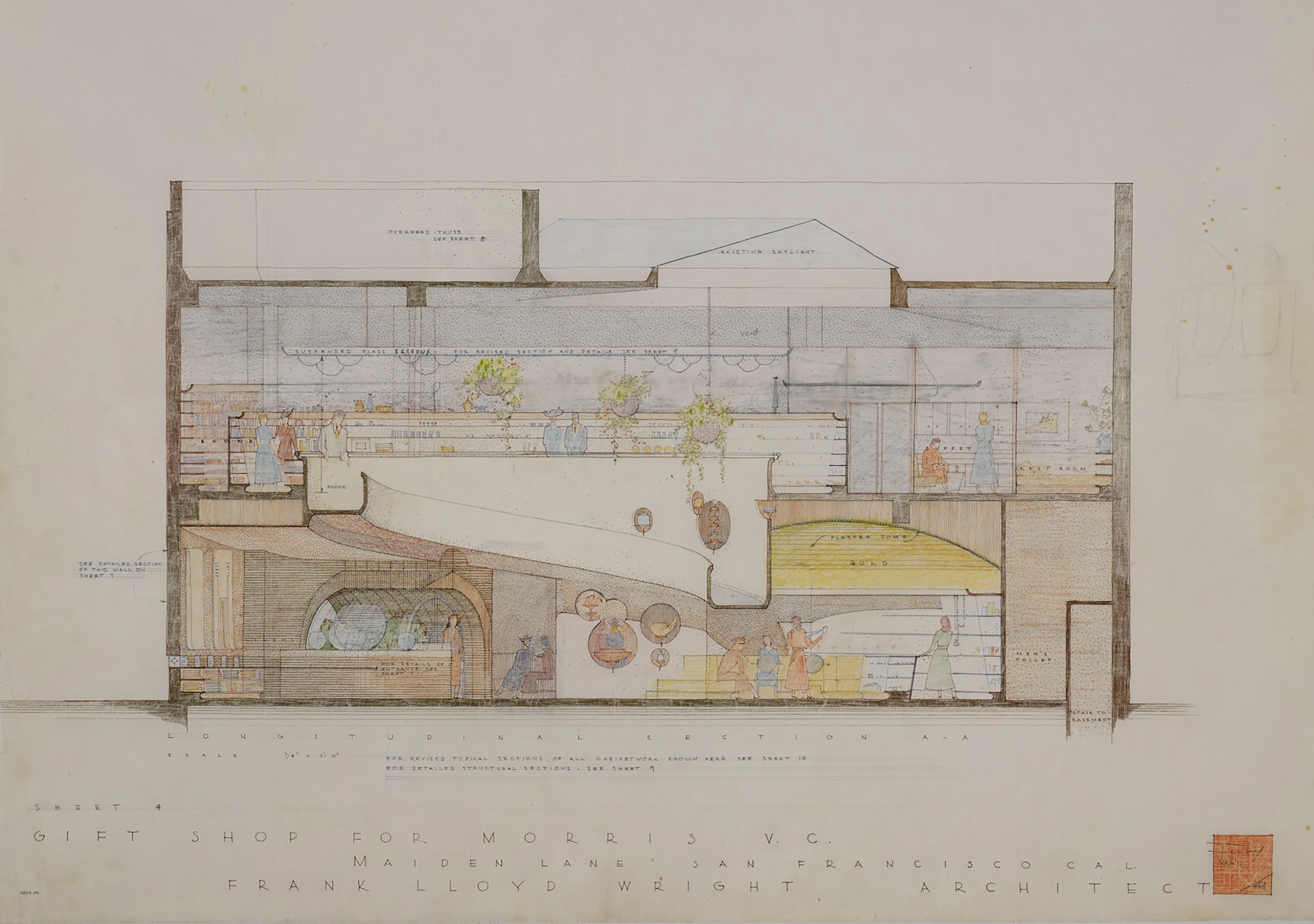

V. C. Morris Shop, San Francisco. 1948 – 49. Longitudinal section. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 29 1/2 × 36” (74.9 × 91.4 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

“Every generation has new questions and new views, even on well-known material,” said Barry Bergdoll, Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design in conversation with MoMA’s director Glenn D. Lowery at a press event last week. “But inevitably an archive of this hugeness is going to have some revelations and new documents.”

The enormous archive, holding 72 years’ worth of Wright’s work, was jointly acquired by MoMA and Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University in 2012. For this summer’s exhibition, the curators had the monumental task of sorting through 55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of correspondence, 125,000 photographs and 2,700 manuscripts as well as models, film and even building fragments from that archive.

MoMA conservator Ellen Moody prepares a wood-and-paperboard model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie Towers for restoration. The tower is one of many featured in the exhibition.

Model of St. Mark’s Tower. Unbuilt project. New York, New York. 1927 – 31. Painted wood. 53 x 16 x 16” (134.6 x 40.6 x 40.6 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. 1943 – 59. Model. Painted wood, plastic, glass beads, ink and watercolor on paper, 28 x 62 x 44” (71.1 x 157.5 x 111.8 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

The exhibition, while extremely detailed, only unveils a sliver of Wright’s work, of which he kept extensive records for posterity. The show is divided into 12 subsections that highlight Wright’s most prominent projects. Each of these mini exhibitions was curated individually by invited scholars, historians, architects and art conservators.

“It’s also key that in this exhibition we’re announcing the much greater accessibility of this archive — that it is here and open to new questions and new people,” said Bergdoll. “That’s why it was important that we invited younger scholars and different voices, people who didn’t necessarily already have their Frank Lloyd Wright credentials and authored three books on the man.”

Galesburg Country Homes, Galesburg, Michigan. 1946 – 49. Site plan. Ink and colored pencil on tracing paper, 46 5/8 x 37 1/8” (118.4 x 94.3 cm). Image courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Rosenwald Foundation School, Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Virginia. Project, 1928. Perspective. Pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper, 12 3/4 x 25 7/8” (32.4 x 65.7 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Little Dipper School and Community Playhouse, Los Angeles. 1923. Perspective from the west. Pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper, 15 3/4 x 26 7/8” (40 x 68.3 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

An essential element to understanding the exhibition are the short films on display in each section where viewers can watch behind-the-scenes footage of the curators sifting through various materials. Each film gives viewers a point of entry into the adjacent drawings. While Wright’s work may be meticulously clear and thorough, it can still be fairly difficult to interpret via the untrained eye.

“We hope that the films are a little bit of an owner’s manual to each room,” said Bergdoll. “You see how a historian confronts an architectural drawing and asks questions about it. Now you think, how do I as a viewer work with these drawings?”

Plan for Greater Baghdad, Baghdad. Project, 1957. Aerial perspective of the cultural center and University from the north. Ink, pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper, 34 7/8 x 52” (88.6 x 132.1 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Jacobs House, Madison, Wisconsin. 1936 – 37. Exterior perspectives. Colored pencil on paper, 21 × 31 3/4” (53.3 × 80.6 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

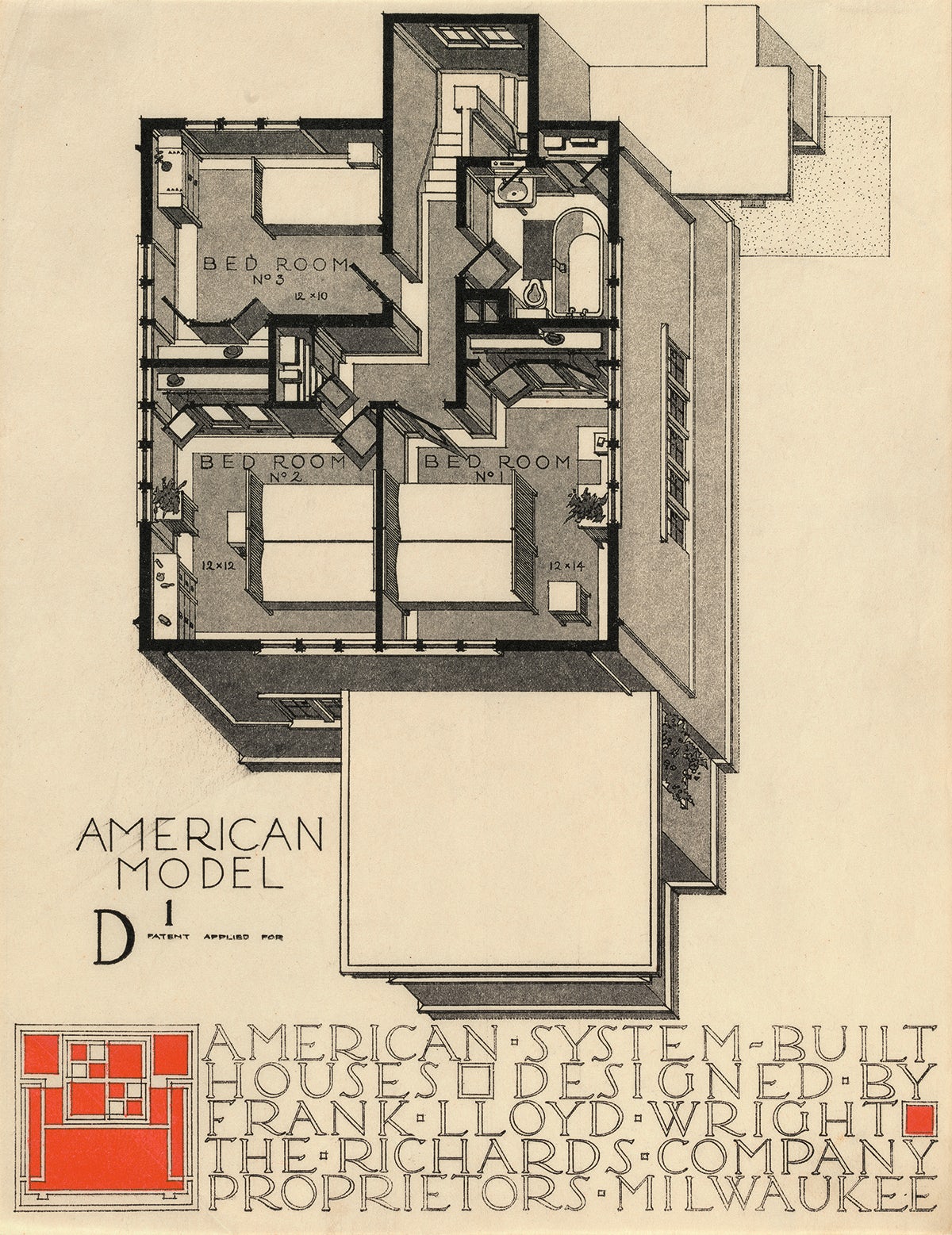

American System-Built (Ready-Cut) Houses. Project, 1915 – 17. Model options. Lithographs, each: 11 x 8 1/2” (27.9 x 21.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gifts of David Rockefeller, Jr,. Fund, Ira Howard Levy Fund and Jeffrey P. Klein Purchase Fund

Now that Wright’s archives are permanently located in New York City, both Bergdoll and Lowery see the potential for his work to be cross-sectionally displayed throughout the museum adjacent to that of other iconic architects such as Mies van der Rohe. Wright has only previously been monographically showcased at MoMA, but with his ever-enduring popularity, there is room for him and his work archive to live on in new and exciting ways.

“As much as the tension and contradictions in Wright’s personality could be explained simply biographically,” said Bergdoll, “I think the vantage point of 150 also allows us to see him at the crosscurrents of culture both nationally and internationally, at any given moment. Now, with that greater distance, as eccentric and highly personal as Wright was, he’s also an intriguing mirror for many big issues.”

Ennis House, Los Angeles. 1924 – 25. Perspective from the southwest. Pencil, colored pencil and ink on tracing paper, 20 1/8 x 39 1/8” (51.1 x 99.4 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Left: The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago. Project, 1956. Perspective with the Golden Beacon Apartment Building project (1956–57). Pencil, colored pencil and gold ink on tracing paper, 8 ft. 9 in. x 30 in. (266.7 x 76.2 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Right: Unveiling the 22-foot-high (6.7-meter-high) visualization of The Mile-High Illinois at the October 16, 1956, press conference in Chicago. Image courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Raul Bailleres House, Acapulco, Mexico. Project, 1951 – 52. Perspective from the patio. Ink, pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper, 31 3/4 x 52 7/8” (80.6 x 134.3 cm). The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Inside “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” even the most non-design-minded viewers will see that Wright was an architect, intellect and character well ahead of his time. He was also a man who was distinctly aware that how he presented himself had an impact on how the public would understand his architecture. The impressive image he cultivated still influences the world today.

From his thoughts on agriculture — as seen in Davidson Little Farms Unit — to his goals in vertical engineering with MileHigh and his desire for nature-based living shown in Fallingwater and Taliesin, Wright appeared to preempt architectural and societal trends and sought out ways to consistently shake up the world of architecture and urban planning throughout his lifetime.

Top: Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland. Project, 1924 – 25. Perspective. Pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper, 19 3/4 × 30 3/4” (50.2 × 78.1 cm). Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)