Hosted in Las Vegas last month, Autodesk University brought with it all the cutting-edge hardware and innovative software you would expect, and more. Industrial-scale 3D printing, robotic design, virtual and augmented reality and intelligent BIM advancements were in the spotlight, giving a tantalizing glimpse of how architecture and technology will be integrated further still in the coming years.

The biggest star of this year’s show, though, was not a single piece of hardware, an updated version of CAD software or a more efficient workflow tool. In fact, it was a fundamental concept: generative design. Taking cues from the evolutionary design structures found within nature, generative design has the potential to change the built environment beyond recognition — and the leaders of tech are more excited about its potential than ever before.

Viewing on mobile? Click here.

“Generative design involves finding high-level goals and constraints and using the power of computation to explore thousands and thousands of design options,” explains research scientist David Benjamin. Such a system can quickly generate optimal structural solutions, with computers being utilized to answer questions such as “What shape of structure would engender the most efficient bridge between two columns?” or “What is the most slender floor slab possible to achieve this cantilever?”

However, displays at Autodesk University illustrated that more complex problems can now be explored, moving beyond structural efficiency to tackle architectural challenges pertaining to comfort conditions and program. For example, one of the exhibits showed a scale model of a hospital, where different parameters for the desired flow of people, light conditions, temperature and even atmosphere could be input, producing thousands of possible layouts for each ward. This kind of software illuminates the potential for generative design to help solve issues far beyond the concerns of form and structure.

Generative design display at Autodesk University Las Vegas; via YouTube

Combining this technology with advancements in additive manufacturing — 3D printing on an industrial, architectural scale — has the potential to fundamentally change how we think about architecture. Instead of designing building envelopes made up of separate layers for heating, ventilation, passive solar gain and other necessities, these needs could be accounted for within a single, complex “skin” that possesses qualities that mimic biological organisms.

The possibilities are startling. Water and gas could flow through man-made “veins” integrated into walls, rendering pipework a thing of the past. Solar data could generate transformable windows that allow light to enter interiors at precisely the right times of day for the needs of inhabitants, meaning that louvers and blinds are banished from buildings for good. The internal structure of metal and carbon fiber elements will be optimized like animal bones, allowing even larger column-free spaces, wafer-thin staircases and the most dramatic cantilevers yet.

The Museum of Contemporary Art & Planning Exhibition (MOCAPE) by Coop Himmelb(l)au, Shenzhen, China

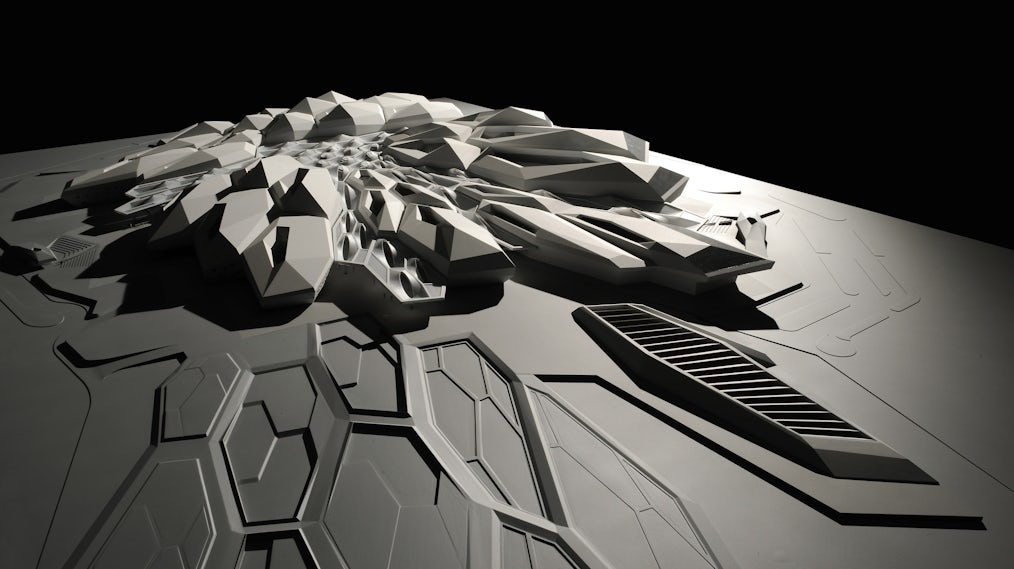

Architects have long been preoccupied with the aesthetic qualities of parametric design. Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher, pioneers of the genre, have been both praised and criticized for implementing fluid, amorphous forms across every typology, while firms such as Coop Himmelb(l)au have investigated robotic construction that would theoretically harness data in a similar fashion, maximizing structural efficiency and radically speeding up the building process.

But Autodesk’s generative design display shows that the work of these experimental practices is the tip of the proverbial iceberg when it comes to data-driven design. It remains to be seen how software and hardware develop in light of these advancements, but one thing is for sure — both architectural design and the construction process will begin to look very different as computation plays an ever-greater role in the industry.

Top image: King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center by Zaha Hadid, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; via designboom