While humans have created shelter out of fabric for millennia, the material is uniquely associated with more recent innovation. At the turn of the 20th century, Vladimir Shukhov applied tensile architecture to the modern city, and by the century’s midway point, the likes of Frei Otto and BuroHappold proved textiles’ creative and functional potential as a construction element.

Yet today’s architects still do not employ fabric as widely as they could. “That fabric appears to be living — that it responds to the wind, that it creates an emotional connection with forces beyond a brick-and-mortar building — can be very inspiring. But that also makes it unpredictable,” reasons Seattle-based landscape architect Daniel Winterbottom. For all of tensile architecture’s allure, practitioners remain unsure of its code-compliant performance and, perhaps, in their own ability to incorporate its waving, billowing, pooling forms into a contemporary design vocabulary.

Building Shade Honorable Mention “The Stripe” by Dimitri Chaava, Stelios Psaltis, Ivane Ksnelashvili, Soso Eliava and Basil Argylopoulos

Winterbottom, along with Miami-based architect Chad Oppenheim and Ennead Architects founding partner Susan Rodriguez, helped expand the design community’s acceptance of tensile architecture as jurors of the fourth annual The Future of Shade, whose winners were revealed last week at the co-working space and event venue LMHQ in New York City. The competition is a partnership between Sunbrella and Architizer promoting imaginative approaches to shading.

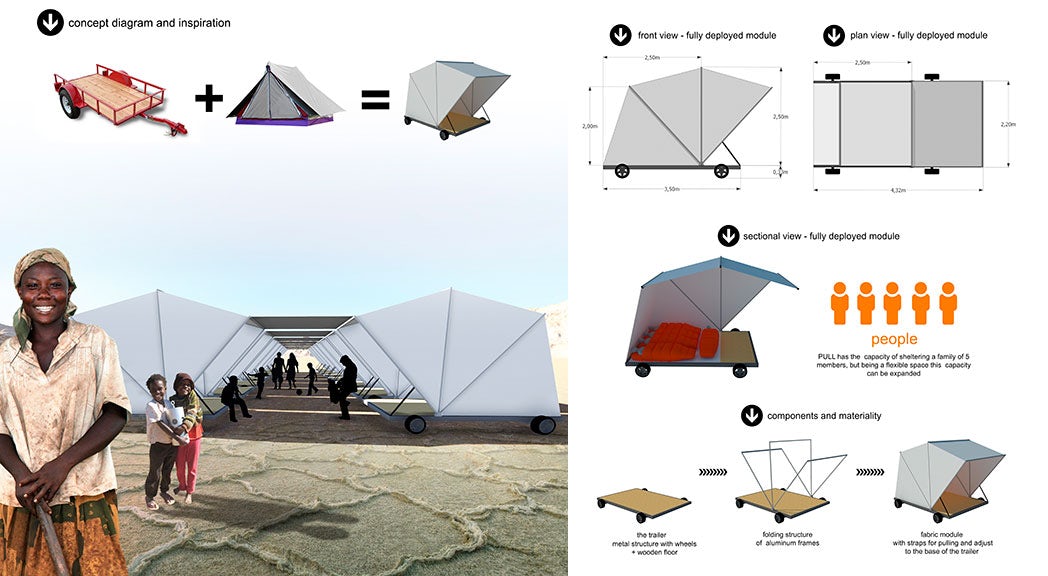

Humanitarian Grand Prize Winner “Pull” by Jonathan Balderrama

The Future of Shade welcomed submissions in three categories: Humanitarian Challenge, focusing on deployable and portable temporary shelter for use in warm climates; Wellness Garden Challenge, which specified a restorative outdoor space for a cancer treatment center; and Building Shade Challenge, in which proposals would mitigate peak daytime sun for Paradise Plaza and the adjoining Paseo Ponti in the Miami Design District.

“Our expectations have once again been exceeded by the enthusiastic and diverse field of entrants to this fourth Future of Shade competition,” says Vince Hankins, industrial business manager at Glen Raven Custom Fabrics. “I believe our decision to expand the scope of the competition into three distinct and relevant categories attracts and appeals to an increasingly global community of architectural professionals who see this event as an opportunity to integrate shade solutions into their design concepts that positively impact humanity. We at Sunbrella are very passionate about enhancing the beauty, enjoyment, and sense of well being in continuously increasing exterior and interior applications, and providing materials that inspire innovation.”

Entries outnumbered last year’s submissions by 30 percent, and prospective solutions were all informed by the various performance criteria and applications of the Sunbrella catalog. Echoing the company’s farther-reaching goal of popularizing fabric as a building block of the constructed world, Rodriguez observes, “It seems the opportunities to capitalize on fabric’s suppleness, changeability and ability to make [a] place with very modest means are really yet to be explored. This future is not unlike the way glass technology has emerged, intensely, over the last 20 years to handle thermal comfort and transparency.”

Jurors underscored this interest by throwing support behind design proposals that could become reality. “Executability was important to us,” Oppenheim says. Humanitarian Challenge–winner Pull, by Cochabamba, Bolivia–based artist and designer Jonathan Balderrama, captured that value best among the category’s entries.

“Pull” by Jonathan Balderrama

Pull envisions durable fabric telescoping into a hatchback-like volume on a metal frame mounted to a wheeled wooden platform. These portable shelters, which ship relatively flat and whose assembled modules can be moved by means ranging from bicycle to harnessed animal, were designed with relief situations in mind. They may also relocate according to the conditional realities that follow a natural disaster or other crisis.

Rodriguez, who likens Pull to a 21st-century Conestoga wagon, also praises the scalability of the solution. Integrated awnings permit a single module to protect more users or at more points in the daily cycle of living. Multiple units can be arranged in face-to-face or circular configurations, the largest of which can support socializing or communal activities like cooking in their protected centers.

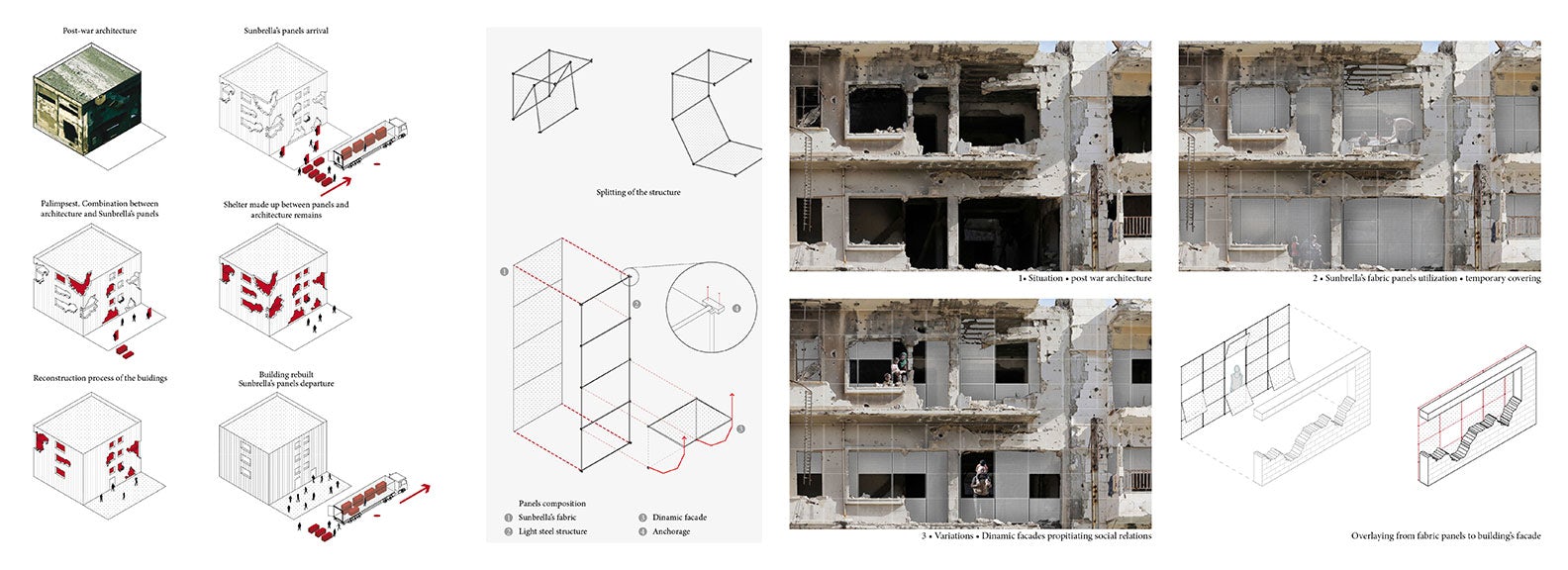

Humanitarian Honorable Mention “Occupying War” by Daniel Zuluaga Giraldo, Iojann Restrepo Garcia and Alejandro Vargas Marulanda

“Occupying War” by Daniel Zuluaga Giraldo, Iojann Restrepo Garcia and Alejandro Vargas Marulanda

Jurors praised both Pull and Wellness Garden Challenge–winner Drapery Scenery for its economy of means. Whereas the former could come to life via a small Kickstarter campaign, the latter, by Berlin-based student Hyunjeong Kim, embodied material efficiency. Drapery Scenery ostensibly uses only fabric, metal frames and foundations.

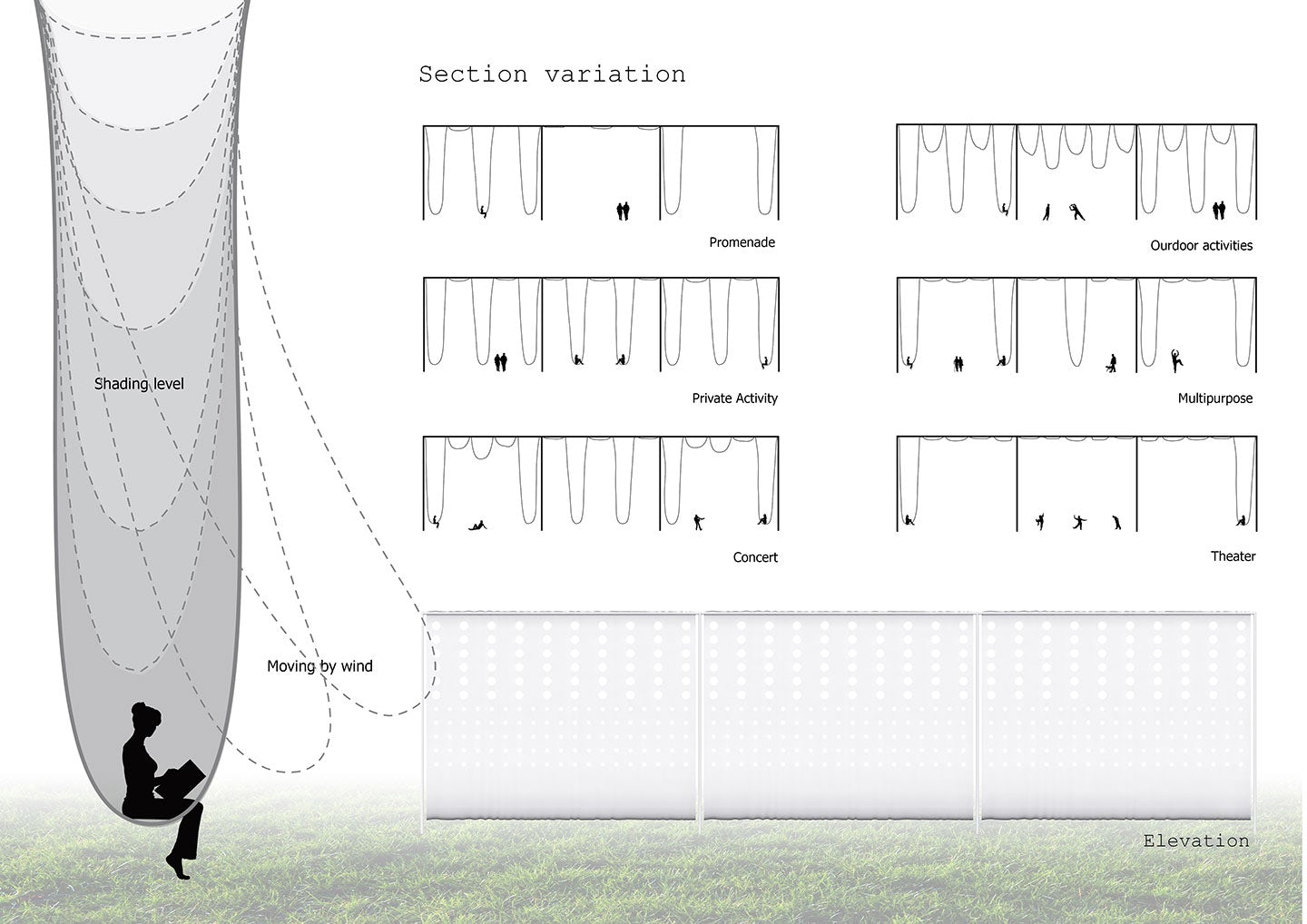

Wellness Garden Grand Prize Winner “Draping Scenery” by Hyunjeong Kim

Considering that the fabric embodies both strength and flexibility, Kim’s submission proposed weaving a continuous sheet of Sunbrella around and over a row of frames spaced asymmetrically. The move produces a series of swags that almost reaches the ground “for relaxing or meditation and functions as [furniture] without any additional elements,” the proposal states. Bench swings alternate with roof planes, opening to the sky and shielding direct sun, respectively, and a pattern of negative spaces laser-cut into the fabric enhance this dialogue with the atmosphere.

“Draping Scenery” by Hyunjeong Kim

By bringing the shading device so close to users, Oppenheim says, Drapery Scenery is able to perform beyond its given function “and become a spatial organization device.” Winterbottom, meanwhile, says the project illustrates his point about tensile architecture’s special relationship to nature. It sways in the wind, frames exterior views and permits various exposures to the sun.

“Draping Scenery” by Hyunjeong Kim

The landscape architect also enthuses about the scheme’s appropriateness to a healthcare environment: After they are admitted into a center for cancer or other treatment, patients are typically stripped of their autonomy — told where to sleep, when to take pills and so forth. Drapery Scenery reinserts choice into the patient’s life, and its geometry changes according to those choices as Kim’s submission explains. “The basic module helps us to make diverse compositions … and this leads to various actions, such as relaxing, promenading, outdoor activities, concerts” or even stretching and pulling the form by grabbing one of its laser-cut holes. “In reacting with users’ gestures, the whole appearance of the structure is changed dramatically, adopting and supporting their poses with tension.”

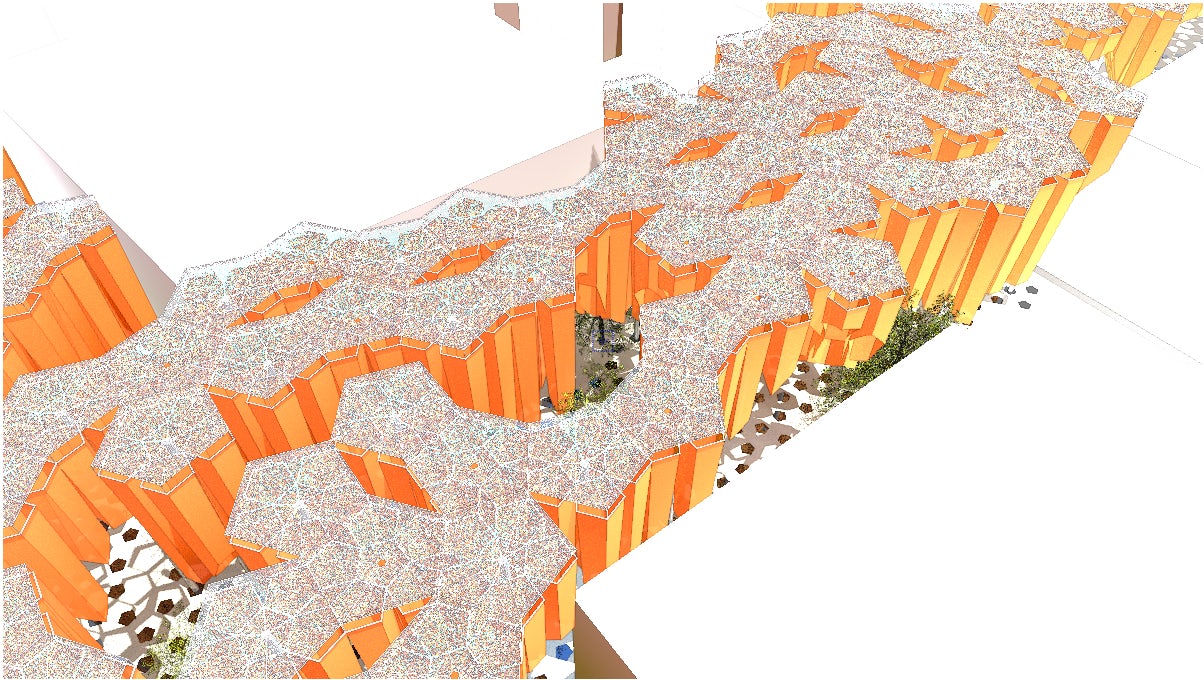

Building Shade Grand Prize Winner “Quasicrystals for Design” by Alberto Adolfo, Fernandez Gonzalez and Carlos Benjamin

Building Shade Challenge–winner Quasicrystals by Santiago, Chile–based architects Alberto Adolfo, Fernandez Gonzalez and Carlos Benjamin reacts to a reality of the commercial realm. In the Miami Design District, luxury consumer brands have invested significant resources in architecture. And while shoppers certainly need protection from the subtropical weather, a shading device cannot necessarily block these stores’ impressive, soaring facades — or their signage.

“Quasicrystals for Design” by Alberto Adolfo, Fernandez Gonzalez and Carlos Benjamin

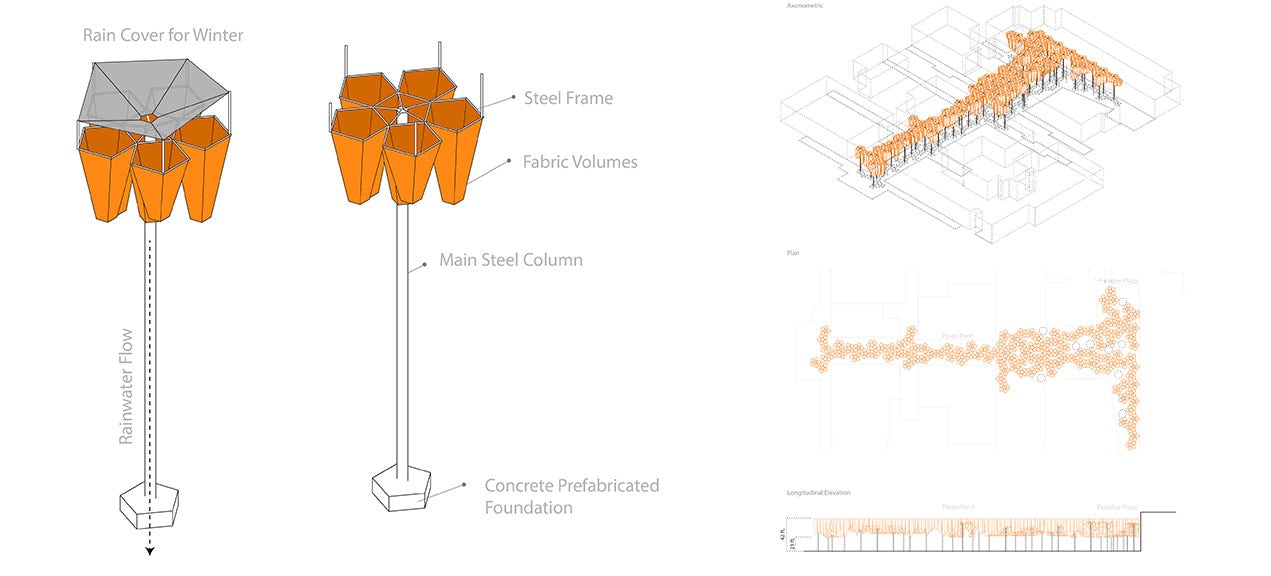

Quasicrystals’ namesake form appears, in plan, as a series of tessellations outlined in steel. In section, each of these shapes is actually extruded in Sunbrella fabric to form volumes that Oppenheim calls lantern-like. The lanterns suspend from steel columns, which may be mounted in precast concrete foundations for uniform coverage or in clusters for visual interest and better sightlines to specific retail elevations.

“Quasicrystals for Design” by Alberto Adolfo, Fernandez Gonzalez and Carlos Benjamin

The competition entry additionally proposes installing a cover over Quasicrystals during Miami’s wet season, with incisions in the cover that allow the steel columns to function as rain chains. Jurors, however, were most impressed with the proposal on its own: By creating shade not through mere coverage, but in their height, the lanterns produce biophilic light patterns on the ground; and by remaining open to the sky, each lantern acts as a thermal chimney that siphons convective heat away from pedestrians. They also imagined layering a lighting design into the concept, to create an event atmosphere for Paradise Plaza and Paseo Ponti at night.

“Quasicrystals for Design” by Alberto Adolfo, Fernandez Gonzalez and Carlos Benjamin

Quasicrystals may also exemplify the executability criterion, as this year, members of the Miami Design District will review all Building Shade Challenge submissions for possible erection in the newly renovated Paradise Plaza and adjoining Paseo Ponti. (Previously, Sunbrella constructed Twisty, a 2013 Future of Shade–winner, as a pavilion.) That designer will receive a $25,000 commission, on top of the $10,000 prizes being distributed to the winners in this year’s three categories.

Building Shade Honorable Mention “The Stripe” by Dimitri Chaava, Stelios Psaltis, Ivane Ksnelashvili, Soso Eliava and Basil Argylopoulos

Perhaps more important, construction will give an extra boost to tensile architecture and, more generally, shift professionals’ notions that “there’s a building with a shading device attached to it,” as Architizer CEO Marc Kushner observed in conversation with the jurors. “Somehow shade tends to be one of those things us architects deal with later. The amazing part of this conversation is the principle that shade can be an initial and leading provocation of a building design.”

“The Stripe” by Dimitri Chaava, Stelios Psaltis, Ivane Ksnelashvili, Soso Eliava and Basil Argylopoulos