Enter the 8th Annual A+Awards for a shot at international publication and global recognition. Submit your projects before March 27th to be in the running.

Speaking to The New York Times in 2016, architect Yen Ha revealed an uncomfortable truth for the profession: Women are still discriminated against in the workplace, facing a daily battle for respect in the studio, on the construction site and everywhere in between.

“We absolutely face obstacles. Every single day,” said Ha. “It’s still largely a white, male-dominated field, and seeing a woman at the job site or in a big meeting with developers is not that common. Every single day, I have to remind someone that I am, in fact, an architect. And sometimes not just an architect, but the architect.”

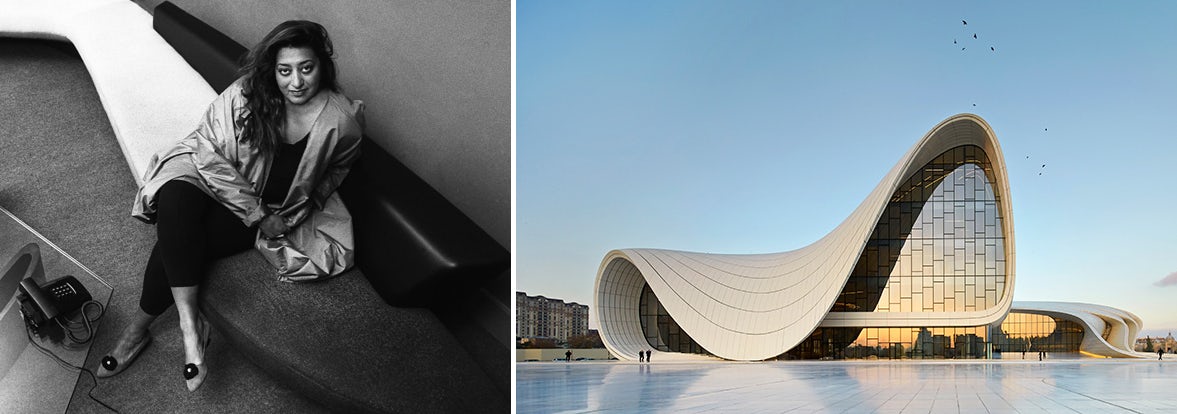

These sentiments were shared among many other female architects interviewed by the Times, their comments coming just a few days after the unexpected death of the ultimate flag-bearer for women in the profession: Dame Zaha Hadid. Hadid herself was well known for lamenting the lack of gender equality within architecture, asserting that, despite campaigns against discrimination in the workplace, “it’s still a man’s world.”

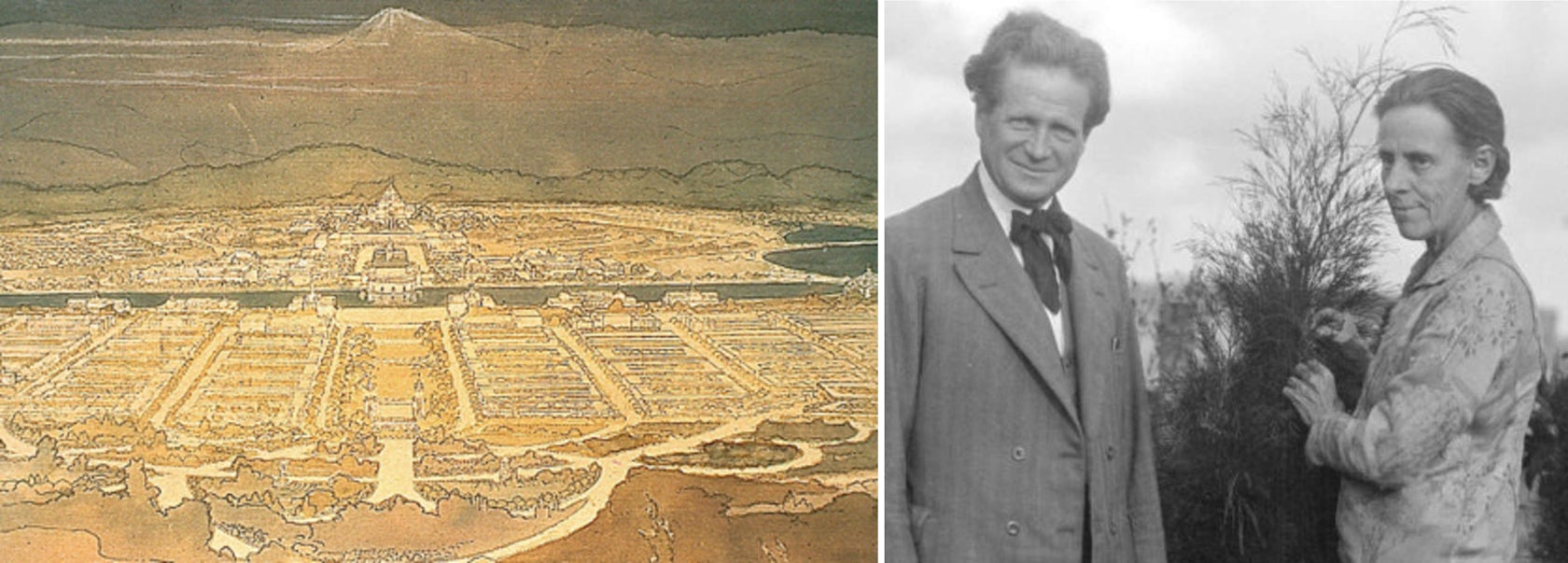

Exactly 50 years apart, these two photographs depict two key women recognized by the A+Awards: Denise Scott Brown in Las Vegas (left); Jeanne Gang picking up the A+Awards Firm of the Year Award (right).

The following month, Architizer’s A+Awards Gala provided a timely reminder not only of Zaha’s extraordinary legacy, but also of a compelling future for female architects. At the forefront of a talented new generation of designers forging new works across the United States and beyond, Jeanne Gang — founder of Chicago and New York–based firm Studio Gang — picked up the coveted Firm of the Year Award.

Two years earlier, Denise Scott Brown received Architizer’s Lifetime Achievement Award, given jointly to her and husband Robert Venturi. It was a significant moment given Scott Brown’s Pritzker Prize snub back in 1991, a scandal that failed to be addressed by the 2014 Pritzker Prize jury despite a petition signed by hundreds of prominent architects including Zaha Hadid and Robert Venturi himself.

Despite steps in the right direction, Ha’s reflections on the state of the profession are proof that more must be done to fight for equality within architecture and the wider construction industry, and the A+Awards aims to be a powerful platform for change in this regard. As we look forward to another significant year for innovative females within the profession, we’ve highlighted 26 women from the present and the past who have changed how we think about the built environment in a myriad of ways.

If you feel we have missed a key name from our list, please don’t hesitate to reach out, and make sure to enter your very best project in the 2020 A+Awards — the final deadline for submissions is March 27th.

Right: Public Farm 1, a 2008 installation on the grounds of Long Island City’s MoMA PS1 by Amale Andraos’s firm, WORKac; the museum described the installation as “a living structure made from inexpensive and sustainable materials recyclable after its use at PS1”; images via MoMA PS1 and Archinect.

Amale Andraos

Over the past two decades, Amale Andraos has distinguished herself as an architect, educator and urban theorist. The dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Andraos is also a founding partner of WORKac, a firm dedicated to “positing architecture at the intersection of the urban, the rural and the natural.” Her publications include the books 49 Cities and Above the Pavement—the Farm!, both of which seek to redefine the relationship between cities, farms and nature.

Left: The Smile, a temporary installation at the 2016 London Design Festival by Alison Brooks Architects in collaboration with The American Hardwood Export Council (AHEC); this minimalist pavilion showcased the structural potential of cross-laminated timber; images via Alison Brooks Architects and Audi Urban Future Initiative.

Alison Brooks

A London-based architect with a sculptor’s approach to shape and proportion, Alison Brooks is one of Britain’s most original architects. In 2013, she received the AJ Woman Architect of the Year Award. One of the judges, Paul Monaghan, applauded the panel’s choice, explaining that “her mixture of sculpture, architecture and detail is what has made her such a powerful force in British architecture.”

Right: affordable modular housing designed by Tatiana Bilbao, Mexico; images via Dezeen and Paperhouses

Tatiana Bilbao

Tatiana Bilbao is well known for designing elegant, geometric residences, but the Mexico City–based architect’s lasting legacy may be the creative solutions she has proposed for sustainable, affordable housing. In 2015, Bilbao sat down for an interview with Architizer to discuss her plan to create a series of highly customizable modular houses that could be assembled for as little as $8,000. “Our idea was to show that there are many possibilities for this house, that you can add volumes, and that you can really continue growing, changing and extending the house the way you want to,” said Bilbao of the project.

Left: SESC Pompeia, Sao Paulo, Brazil; images via ArchDaily

Lina Bo Bardi

Lina Bo Bardi (1914 – 1992) was an Italian-born, Brazilian architect best known for her expressive use of materials and her lifelong exploration of the social possibilities of design. Her one-of-a-kind sensibility found its fullest expression in her 1982 masterwork SESC Pompeia, a converted factory featuring aerial walkways and asymmetrical portholes in place of windows. There is no other building quite like this “factory leisure center,” which is reason enough to plan a trip to Sao Paulo this winter.

Right: VSBA’s Provincial Capitol Building, Toulouse, France, photo by Matt Wargo; images via designboom and Architizer

Denise Scott Brown

Innovative architect, groundbreaking theorist and spouse of Robert Venturi — with whom she founded the firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates — Denise Scott Brown is a true American icon. In 2015, Scott Brown and her husband were the dual recipients of Architizer’s A+Lifetime Achievement Award. A fitting choice, too, as this pair did more to shape what we know as “Postmodernism” than virtually any other creative team. “There is no immaculate conception of ideas,” Scott Brown told Architizer in an interview conducted in conjunction with the award. “Collaboration is the truth of architecture.”

Left: Privacy and Publicity, one of Beatriz Colomina’s best-known critical works, and Sexuality and Space,an anthology of writings on architecture edited by Colomina; images via Princeton University and Archinect

Beatriz Colomina

One of the world’s foremost architectural historians, Colomina’s research focuses on the relationship between architecture and the media. Her interest in linking architecture to other disciplines has been truly transformative for the Princeton University School of Architecture, where she founded the school’s “Media and Modernity” graduate program. “Modern architecture,” she once wrote, “only becomes modern with its engagement with the media.” Her work is a must read for anyone interested in the relevance of architecture to broader questions of modernity.

Right: The Women’s Opportunity Center in Kayonza, Rwanda; images via Architizer and Pinterest

Sharon Davis

Architecture is a second career for Sharon Davis, who switched gears after many years working in finance. However, once her degree was in hand, Davis wasted no time making a name for herself. Her first major project was the widely acclaimed Women’s Opportunity Center in Rwanda. As Architizer reporter Emily Nonko explained, this project “had to address more than the lack of a safe gathering place for Rwandan women — it also had to create economic opportunity and a solid social infrastructure.”

The scheme Davis developed is functional and comfortable: a campus that includes a farmer’s market, gardens, guest residences and community space, all arranged in a circular formation. It certainly lives up to the transformational vision outlined by Davis on her website, which asserts the firm’s aim to “design extraordinary buildings that alter the future of communities.”

Left: “Phantom Restaurant, Opera Garnier,” Paris, France; images via Studio Odile Decq and dezeen

Odile Decq

Odile Decq is an architect whose work speaks to the imagination. Her “Phantom Restaurant” in Paris’s celebrated Opera Garnier is a study in colliding temporalities, with red and white biomorphic forms challenging the opera house’s vaulted beaux arts ceiling. As any good opera fan knows, however, a conflict can be made harmonious. At the “Phantom Restaurant,” old and new styles partake in a kind of dance that heightens the drama of each. Indeed, boldness is a cornerstone of Decq’s entire body of work, which offers a sharp rebuke to the idea that elegance is defined by restraint.

Right: The Institute of Contemporary Art overlooking Boston Harbor; images via designboom

Liz Diller

A founding partner of the celebrated firm DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO, Liz Diller has been on the cutting edge of art and design since the late ’70s. With conceptual projects like the Blur Building — an inhabitable, man-made cloud that served as a media pavilion during Swiss EXPO 2002 — and functional landmarks like Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art to its credit, Diller’s firm has certainly earned its reputation for innovation.

Diller credits her background as an artist for her ability to remain free from established architectural conventions. “The early years gave me an opportunity to take a critical stand and challenge what architecture is and how it can interact with other cultural disciplines,” she explained. “I couldn’t have started by building buildings right away.”

Left: University of Ibadan in Nigeria; images via Architecture.com and the Transnational Architecture Group

Jane Drew

Jane Drew (1911 – 1996) was an English architect who made waves not just for being a prominent woman architect — which was notable enough in mid-century Britain — but as an outspoken proponent of Modernism. An architect with social and international interests, Drew’s extraordinary career saw her take on major projects in West Africa, India and Iran in addition to her native England. In her phrase, she designed “everything from kitchens upward,” and always with an eye toward combining form and function.

Right: the Eames House, Pacific Palisades, Calif.; images via Daniella On Design and Living Edge

Ray Eames

Along with her husband, Charles Eames (1907 – 1978), Ray Eames (1912 – 1988) defined modernist cool for a generation of Americans. In addition to the iconic molded-plywood Eames lounge chair, the duo is known for building the Eames House in Los Angeles entirely out of prefabricated steel parts intended for industrial construction. The building, which would serve as the couple’s home and studio for decades, was completed in a manner of days, upending longstanding ideas about efficiency and quality.

Left: Aqua Tower, Chicago, Ill.; images via Architizer and the Wall Street Journal

Jeanne Gang

MacArthur fellow and founder of Studio Gang in Chicago, Gang is one of America’s foremost architects. Her 82-story skyscraper, Aqua, is right at home in the Windy City, a metropolis known for its iconic towers. Although she is as much of a visionary as any other architect to make their mark on Chicago, Gang’s philosophy of creativity stresses humility and open-mindedness. “Good ideas come from everywhere,” she once said. “It’s more important to recognize a good idea than to author it.”

Right: House on a Cliff, Stockholm, Sweden; images via ArchDaily and Petra Gipp arkitektur

Petra Gipp

Sweden is a cold place, a fact that is reflected in the nation’s literature as well as its architecture. Petra Gipp’s work, with its clean lines and preference for raw surfaces, is certainly part of this tradition. Her work shows us how, when done right, coldness can be comforting.

Left: e.1027, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France; images via Architect Magazine and Wikipedia

Eileen Gray

A pioneer in both her personal life and in her career, Eileen Gray (1878 – 1976) is one of the most significant designers to ever come out of Ireland. While she was renowned for her furniture designs, Gray was also an architect, living for years in e.1027, a home she designed for herself in the south of France. The property was famously vandalized by a certain Le Corbusier, but Gray’s midcentury icon — and her creative legacy — survives today. “To create,” she once said, “you must first question everything.”

Right: split level residence in Tokyo by Atelier Bow-Wow; images via designboom

Momoyo Kaijima

A founding partner of Atelier Bow-Wow, Momoyo Kaijima is among a handful of elite architects who is as capable a theorist as she is a designer. Readers interested in learning more about her firm’s sensibility should check out Made in Tokyo, a guidebook for Kaijima’s native city that focuses on, as Amazon puts it, “the architecture that architects would like to forget.”

In this and other projects, Kaijima and the rest of her team at Atelier Bow-Wow are unflagging in their attempt to understand how spaces are actually utilized in the trenches of daily life. Indeed, the firm’s empirical ethos can be summed up by Kaijima’s personal motto: “Passion without knowledge is a runaway horse.”

Left: Marion Mahony Griffin’s proposal for the planned city of Canberra, the Australian capital; right: Mahony Griffin with her husband and collaborator, Walter Burley Griffin; images via Australian Design Review and The Canberra Times

Marion Mahony Griffin

There are pioneers, and then there is Marion Mahony Griffin (1871 – 1961), one of the first licensed female architects in the world. As a founding member of the prairie school, Mahony Griffin worked with Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Burley Griffin, who she would later marry. With Burley Griffin, she helped plan the city of Canberra, capital of Australia, according to prairie school design principles.

Right: The Death and Life of Great American Cities; images via Wikipedia and textosa

Jane Jacobs

If a library contains only one book on urban planning, chances are it is Jane Jacobs’s 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs resisted the trend toward “urban renewal” and celebrated the functionality of neighborhoods that were allowed to develop spontaneously. “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody,” she wrote. Ms. Jacobs passed away in 2006.

© Eric Staudenmaier

Left: Vault House, Oxnard, Calif.; images via ArchDaily and @slj_lee on Twitter

Sharon Johnston

One of the chief joys of reading architecture blogs like this one is imagining yourself inhabiting fantastical, otherworldly houses. Sharon Johnston and her firm, Johnston Marklee, are keenly aware of this relationship between architecture and fantasy. Time and again, they create structures such as Vault House in Oxnard, California: buildings that are playful, elegant and seem to belong more to the future than the present.

Right: Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington, D.C.; images via Makers and Blackbutterfly7

Maya Lin

An architect, sculptor and land artist, Maya Lin’s career has been marked by achievement in diverse fields. However, she is best known for a project she conceived while still a student: the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. A two-acre plot framed by a wall displaying the names of all the American soldiers lost in the conflict, this monument was considered controversial at the time due to its minimalism.

Today it is widely seen as a masterpiece, an unsentimental, clear-eyed tribute to a conflict that left a deep and lasting scar on the nation. “The definition of a modern approach to war,” she said, “is the acknowledgment of individual lives lost.”

Left: Neri Oxman’s silk pavilion, constructed by letting silkworms loose on a carefully designed steel frame; images via Wikipedia and Architizer

Neri Oxman

Some architects strive to speak to the present moment; others keep their eyes fixed on the future. Neri Oxman is this latter type. An Israeli-American architect, designer and academic, Oxman is well known for her interest in applying findings from biology and computer science to architecture, a field that she believes will be radically upturned in the coming years. “I believe in the near future, we will 3D-print our buildings and houses,” she once said.

Right: The Barcelona Chair; images via Knoll and Lilly Reich

Lilly Reich

Lilly Reich (1885 – 1947) was a German modernist designer best known for her collaborations with Mies van der Rohe. Many people don’t know that she was a full co-creator — not just a collaborator — in the design of the Barcelona Chair, a piece of furniture that remains a symbol of elegance and sophistication. “It became more than a coincidence that Mies’s involvement and success in exhibition design began at the same time as his personal relationship with Reich,” said Albert Pfeiffer, Vice President of Design and Management at Knoll.

Left: The New Museum by SANAA, New York; images via Encyclopædia Britannica and IncredibleWorld.net

Kazuyo Sejima

Kazuyo Sejima of SANAA is an architect who understands how much can be done with simple geometric elements. Take her design for the New Museum in New York: While the scheme is quite minimal — a series of stacked cubes — their offset arrangement ensures that it is one of the most striking buildings on the Bowery.

Right: 200 Eleventh Avenue, a new residential project in New York City; images via Selldorf Architects

Annabelle Selldorf

With Annabelle Selldorf, it’s all in the details. Paul Goldberger, former architecture critic for the New Yorker, described her style as “ … a kind of gentle modernism of utter precision, with perfect proportions.” For her part, Selldorf describes her praxis as follows: “I seek a certain kind of logic that allows you to move in space and perceive it as beautiful and rational.”

Left: Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles, Calif.; images via VieDesign and Women in Architecture

Norma Merrick Sklarek

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926 – 2012) was the first major African-American woman architect, a true trailblazer. Her best-known projects, including Terminal One at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and the Pacific Design Center, reveal an idiosyncratic sense of line and color. Sklarek once illuminated the challenges she faced entering the profession, saying: “The schools had a quota and it was obvious, a quota against women and a quota against blacks. In architecture, I absolutely had no role model. I am happy today to be a role model for others that follow.”

Right: August Wilson Center for African American Culture, Pittsburgh, Pa.; images via Cultural District and The Khooll

Allison Williams

Over the course of her decades-long career, Allison Williams has worked on many major projects at some of the world’s most high-profile firms, including San Francisco’s Perkins+Will and AECOM, where she currently serves as the Design Director.

Her best-known buildings, including the August Wilson Center for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, illustrate her commitment to maximizing the potential of the site. The August Wilson Center, for instance, is spacious, open and luminous despite the fact that it is situated on a tight street corner.

Left: Heydar Aliyev Center, Baku, Azerbaijan; images via designboom and Wired

Zaha Hadid

When Zaha Hadid passed away in March 2016, she was one of the world’s best-known and most-loved architects. Her work, with its daring lines and sculptural expressiveness, is powerful enough to turn anyone into an architecture fan. Hadid’s unique vision allowed her to push digital and visual technologies to their full potentials, creating buildings that can only be described as transformative. “I don’t think you can teach architecture,” she once said. “You can only inspire people.”

Introduction by Paul Keskeys. Make sure your firm submits its best work for the 8th Annual A+Awards, the world’s largest awards program for architecture and building-products.