Deadline extended! The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Extended Entry Deadline on February 27th!

Architects have been involved in set design for all kinds of performance since the time of Palladio, and opera is no exception. One of Mozart’s most popular operas, “The Magic Flute,” is visually synonymous with Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s rapturously mystical stage designs from 1816. More recently, as opera has continued to reinvent itself for new audiences, it has tapped into big-name architects to draw in fresh crowds and creative ideas.

Schinkel’s design for “The Magic Flute.” Image courtesy Wikipedia

Architects get something out of it, too. Besides being an opportunity for them to show off in front of a theater full of well-heeled potential clients, the opera stage offers them a chance to try out some of their most dramatic concepts on an open platform with no programmatic constraints.

Because opera stages are so intensely mechanical, architects can also use them to do things that would not be possible in a conventional project. As Rafael Viñoly puts it: “Designing sets is an interesting field because you’re dealing with ideas that are only suggested; you’re not dealing with the requirements needed for an architectural space.” Floors can move, projections can be used to disorient or obscure and platforms can be stacked, rearranged or replaced with giant clouds of paper.

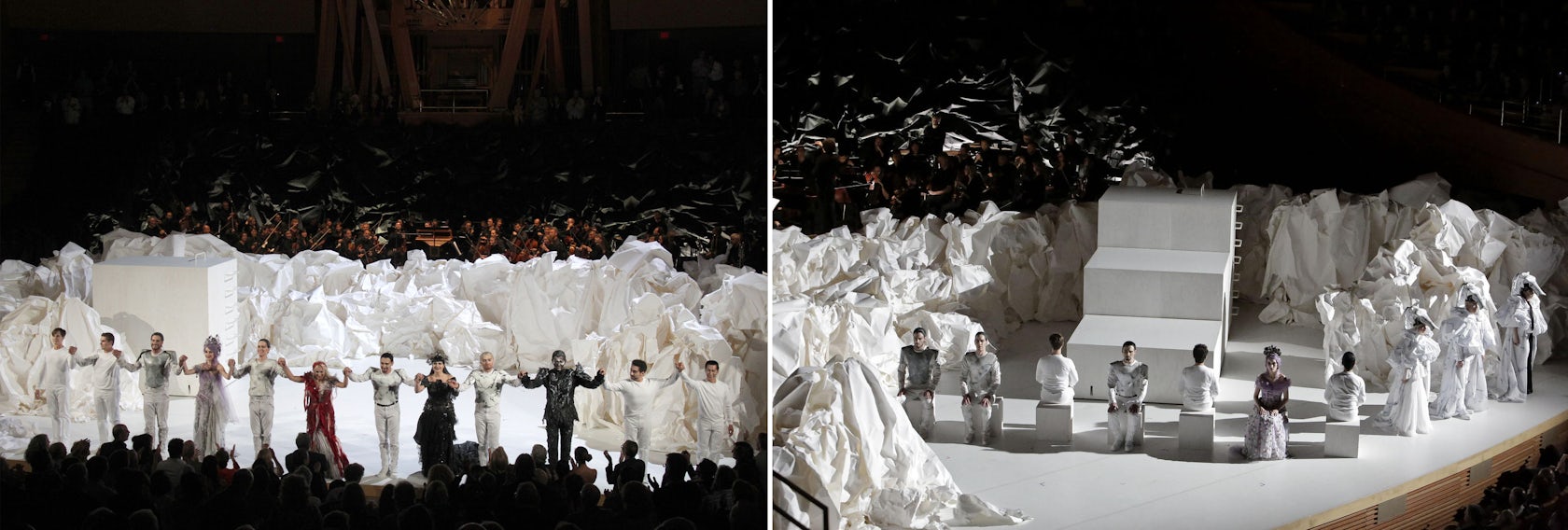

Frank Gehry’s “Don Giovanni” set design. Photos courtesy the Los Angeles Times

Frank Gehry

In 2012, the LA Philharmonic invited three architects to design sets for three of Mozart’s most popular comic operas over three successive seasons. Prominent fashion designers were paired with each architect to design the costumes for each performance, creating a star-studded cultural extravaganza. The performances highlighted their then-new celebrity conductor, Gustavo Dudamel, in the Frank Gehry–designed Walt Disney Opera House. Gehry opened the series with a set for “Don Giovanni” with costumes by LA designers Rodarte. The design featured a movable series of blocks adrift in a sea of sculptural white and black paper puffs.

Jean Nouvel’s set for “The Marriage of Figaro.” (Left) photo courtesy Domus. (Right) photo courtesy 10 Corso Como

Jean Nouvel

Nouvel took his turn in 2013 when he designed the sets for “The Marriage of Figaro” with couturier Azzedine Alaïa on costumes. The set was built around a grand central staircase and was washed in electric reds and greens. A grand armchair sat atop the stairs, and it was variously occupied by characters who cycled through positions of power throughout the show.

Zaha Hadid’s set for “Così fan Tutte.” (Left) photo courtesy the New York Times. (Right) photo courtesy Domus

Zaha Hadid

In 2014, Hadid designed the set for “Così fan Tutte” with costumes by designer Hussein Chalayan. The white whorl that sat on the stage undulated with the twists and turns of plot, rippled by internal machinery that would bend and distort the white surface. The design referenced the sandy beaches where the opera is set and the convoluted relationships that are the source of the drama and comedy of the show.

“Attila”stage design by Herzog & de Meuron. Images courtesy Herzog & de Meuron

Herzog & de Meuron

In 2010, the Swiss duo designed sets for Verdi’s opera “Attila” staged at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Costumes were created by fashion designer Miuccia Prada. The show, set during the downfall of the Roman Empire and the invasion by Attila the Hun, began with a stage full of broken chunks of concrete that gave way to a lush jungle in the second act, evoking the same sense of physical chaos and natural overgrowth at work in their buildings like the Perez Art Museum or CaixaForum.

Libeskind’s design for “St Francis of Assisi.” Images courtesy Studio Libeskind

Daniel Libeskind

Daniel Libeskind has had a musical life. He was a young prodigy on the accordion and piano who performed at Carnegie Hall. He has said that the unfinished Arnold Schoenberg opera “Moses and Aaron” inspired much of his breakthrough design, the Jewish Museum of Berlin. In 2002, Libeskind designed a set for the Deutsche Opera’s “St Francis of Assisi,” a 1983 show by composer Olivier Messiaen. The set was composed of a rotating field of cubes engineered by Cecil Balmond.

Libeskind’s design for “Intolleranza.” Images courtesy Studio Libeskind

This was not his first foray into opera. He had previously designed both the set and costumes for “Tristan and Isolde,” an opera by Richard Wagner, and the set for “Intolleranza” by Luigi Nono.

Viñoly’s design for “The Nose.” Images courtesy Rafael Viñoly Architects

Rafael Viñoly

Rafael Viñoly was born into the opera. His father was a director of the National Opera in Uruguay, and he has gone on to design multiple productions, including two stages for productions at Bard College’s SummerScape festival in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. The first was for Shostakovich’s “The Nose” in 2004, which featured angular screens that opened and closed to frame the action of the Modernist opera, at one point forming a triangle subtly evocative of the work’s namesake.

Viñoly’s design for “Die Liebe der Danae.” Images courtesy Rafael Viñoly Architects

In 2011, Viñoly returned to Bard to design the stage for Richard Strauss’ rarely performed “Die Liebe der Danae,” which had the stage dripping in gold for the tale of King Midas.

Viñoly’s design for “The Return of Ulysses.” Images courtesy Rafael Viñoly Architects

In between, he worked on the sets for the Chicago Opera Theater’s 2007 production of Claudio Monteverdi’s “The Return of Ulysses.” This set featured a blocky staircase that the heroes and villains of the classically themed opera would ascend and conquer. At various points, characters would erupt from the inside of the stair while the stage was washed with light.

These transformations and spectacular effects are part of what makes opera so alluring to architects. They are the freedoms that static buildings don’t allow. As Viñoly says: “Working on an opera is so different from the work we do as architects, which is limited by various requirements and a complex set of restrictions. Working in the theater gives you the freedom for the creation of magic. It is really quite extraordinary.”

Deadline extended! The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Extended Entry Deadline on February 27th!