Sign up to be informed when the next One Drawing Challenge competition opens for submissions. Be sure to check out the rest of this year’s extraordinary Winners and Commended Entries.

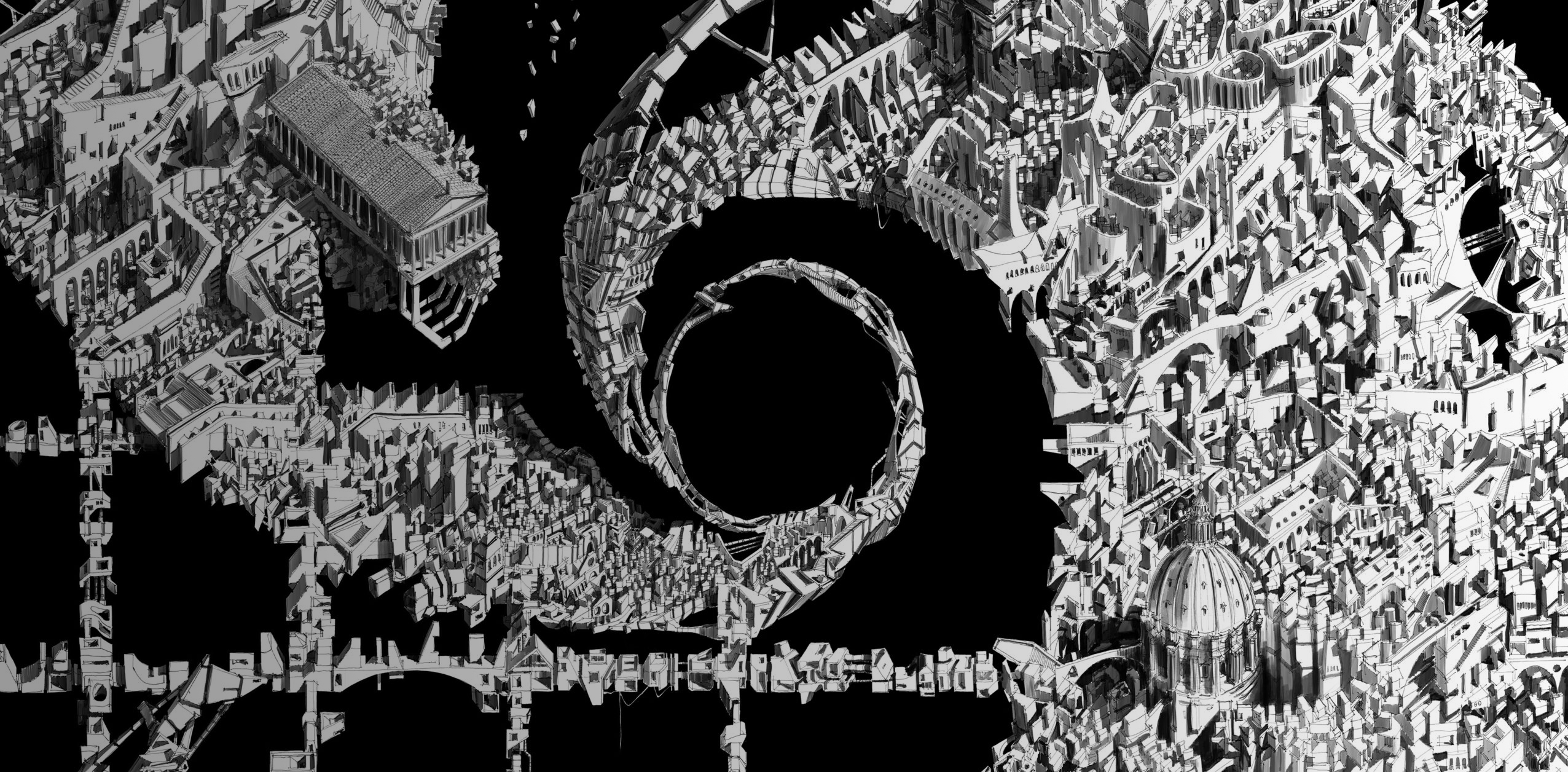

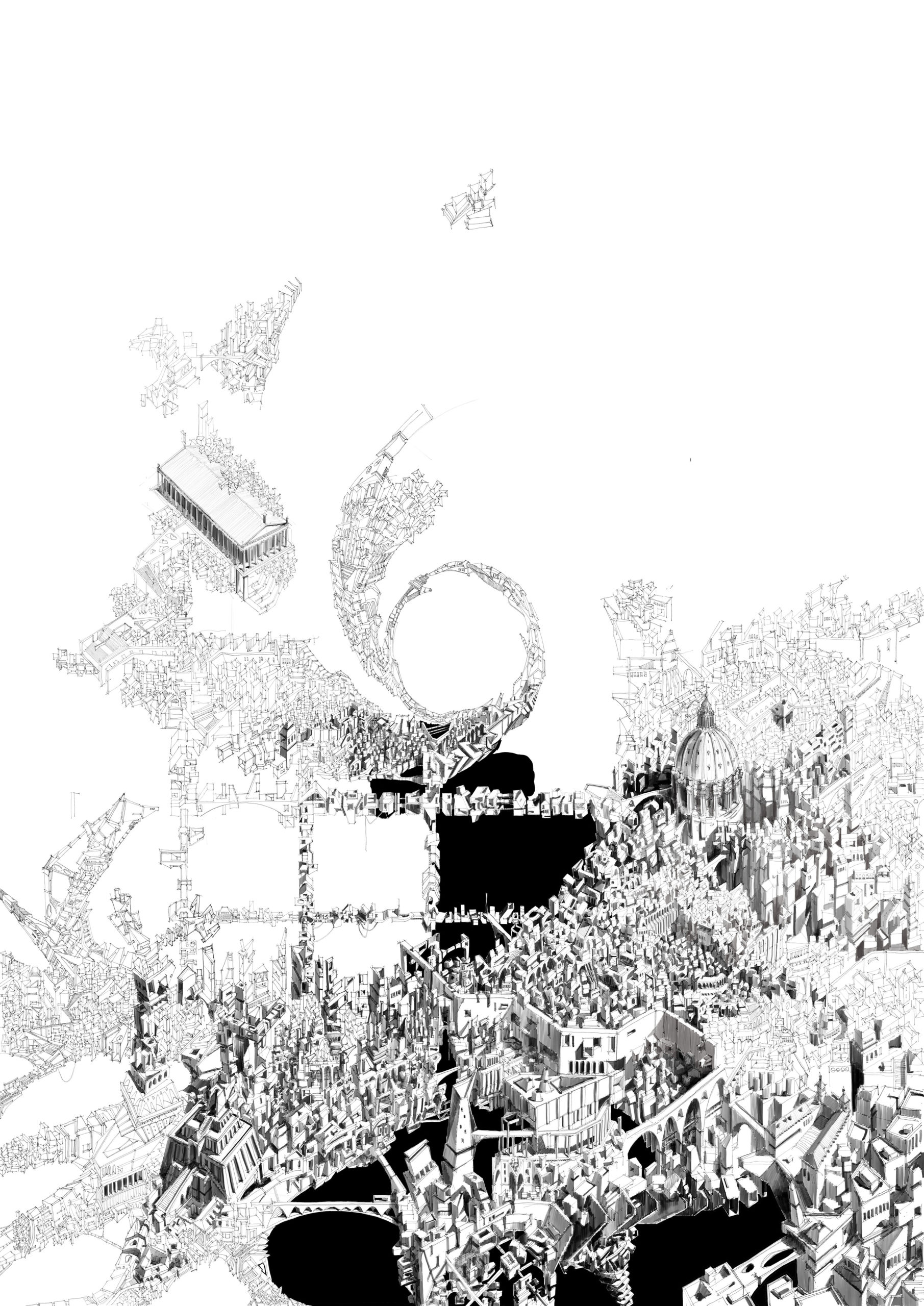

The Non-Student Grand Prize Winner of the 3rd Annual One Drawing Challenge was Endrit Marku, a Lecturer at Polis University in Albania, for his frenetic, surreal drawing, entitled Vortex. Marku’s seemingly never-ending sketch depicts the dizzying dissolution of civilization. Ny representing our inherited buildings as part of a larger, spiraling urban continuum, his drawing reveals the false illusion of permanence that architecture impresses upon the lived present; the impossibility of prolonged stability and the inevitable, entropic fate that befalls the material world.

After a summer of seemingly relentless natural catastrophe, as the climate emergency grows increasingly dire, and at a time where social inequities are being exacerbated, the alarming fragility of our world and the present has never felt more palpable. Endrit’s drawing uses architecture as an allegory, perfectly capturing this sensation in a terrifying beautiful way.

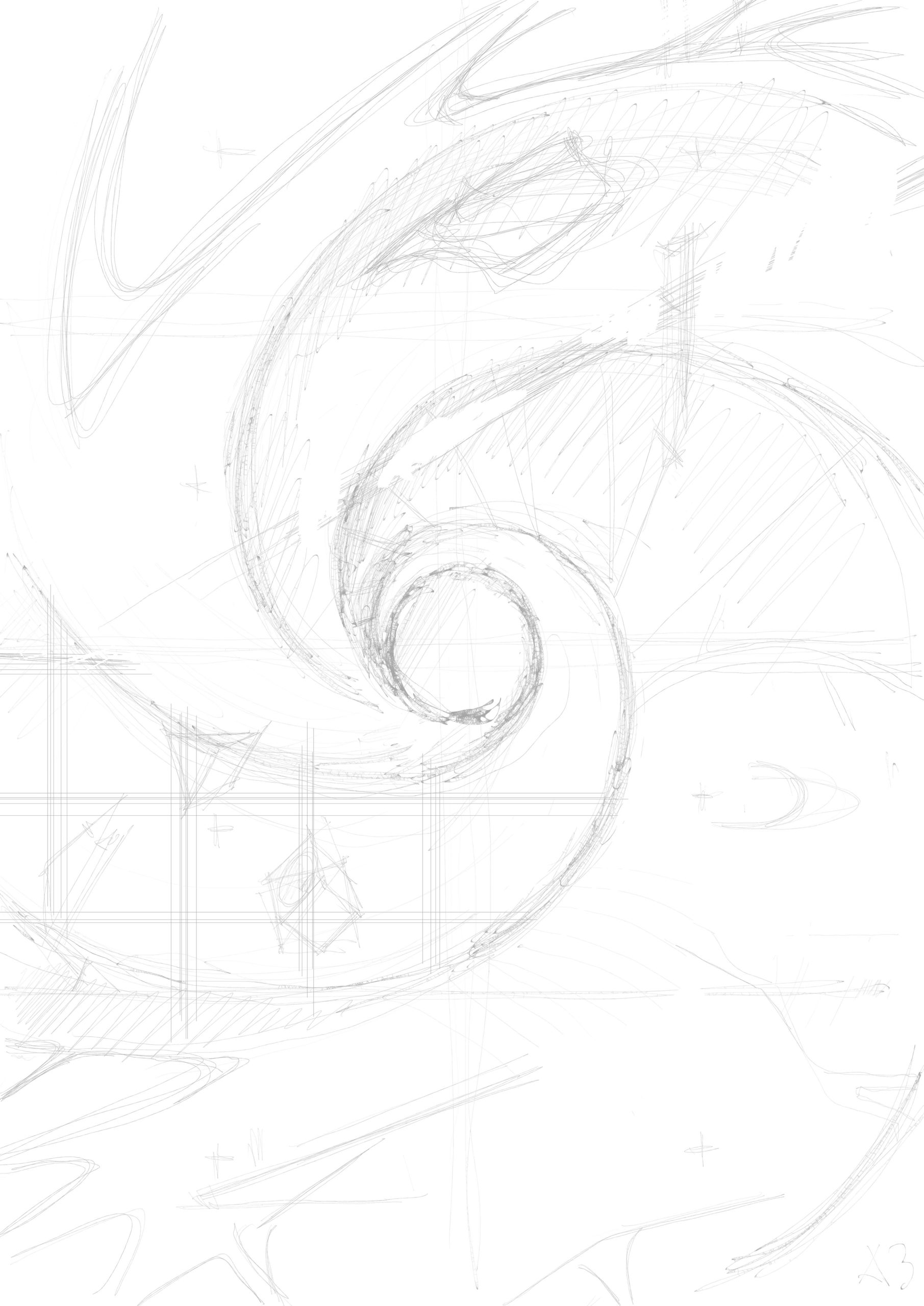

Process image of the structure (scaled).

How did his extraordinary image come into be, and what exactly inspired it? We spoke to Endrit about the creative process — illustrated here with incredible images that reveal the evolution of the award-winning piece — and asked him to reflect on the role architectural drawing in practice and as a practice,

Hannah Feniak: Congratulations on your success with the One Drawing Challenge! What sparked your interest in entering the competition and what does this accolade means to you?

Endrit Marku: Thanks a lot, these last days have been special. Well, architects and competition have quite an intense relationship. Building an important piece of architecture and winning a competition are desires that are injected to us since the initial academic years in the competitive environments of design studios. As an architect who loves drawing, it came naturally to search for a competition rather than, let’s say, finding an art gallery to exhibit my work. In this search it is impossible to miss the Architizer’s event. Winning was beautiful and unexpected. It is highly motivational having your work acknowledged internationally by reputable experts.

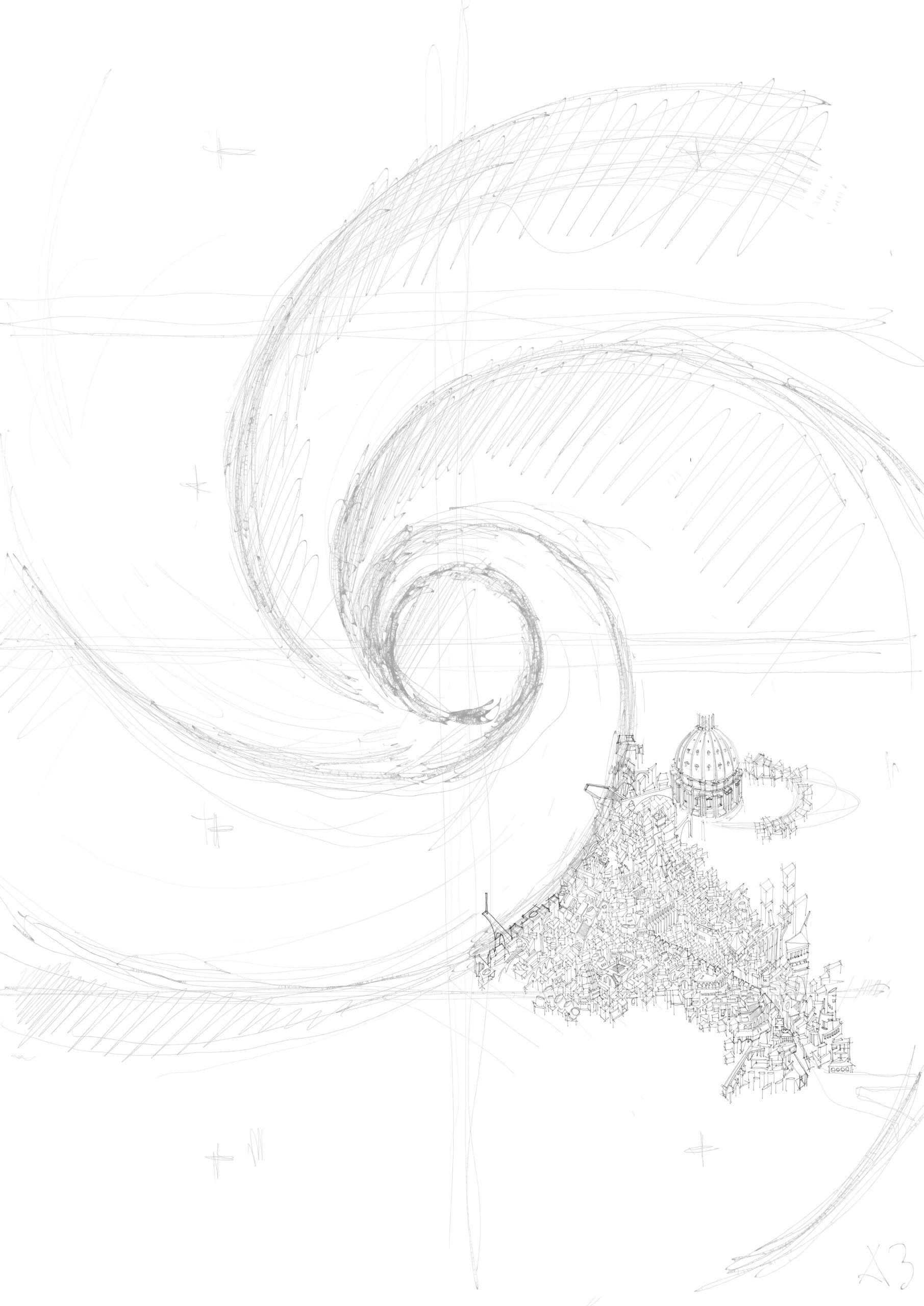

Process image of the filling and detailing.

What were the primary challenges of conceiving your work, from forming the idea to the physical process of drawing?

The idea is only a moment an inspiration, while turning it into a work of art is a way longer process. I enjoy it so I don’t charge it with too many expectations. I mean it is a drawing; if it wasn’t turning out as it expected, I could just decide to put it aside, and start on a new subject. One of my main challenges is time — especially in this series I’m working on, to which Vortex belongs.

I appreciated how my work was defined in the official announcement on your website, as a never-ending sketch, and indeed the process of filling and detailing and finally completing the work is long. It takes days and weeks and requires much patience. Finding time isn’t easy, I have to cut it out from my afterwork hours and weekends. Another challenge is the non-linearity of the process, so I have to stop often to search for the elements I decide to add, how the lantern of the San Peter’s basilica is made or how many columns has the Parthenon’s peristyle. A last challenge is trying not to repeat myself, so I have to combine different types of urban patterns and building typologies.

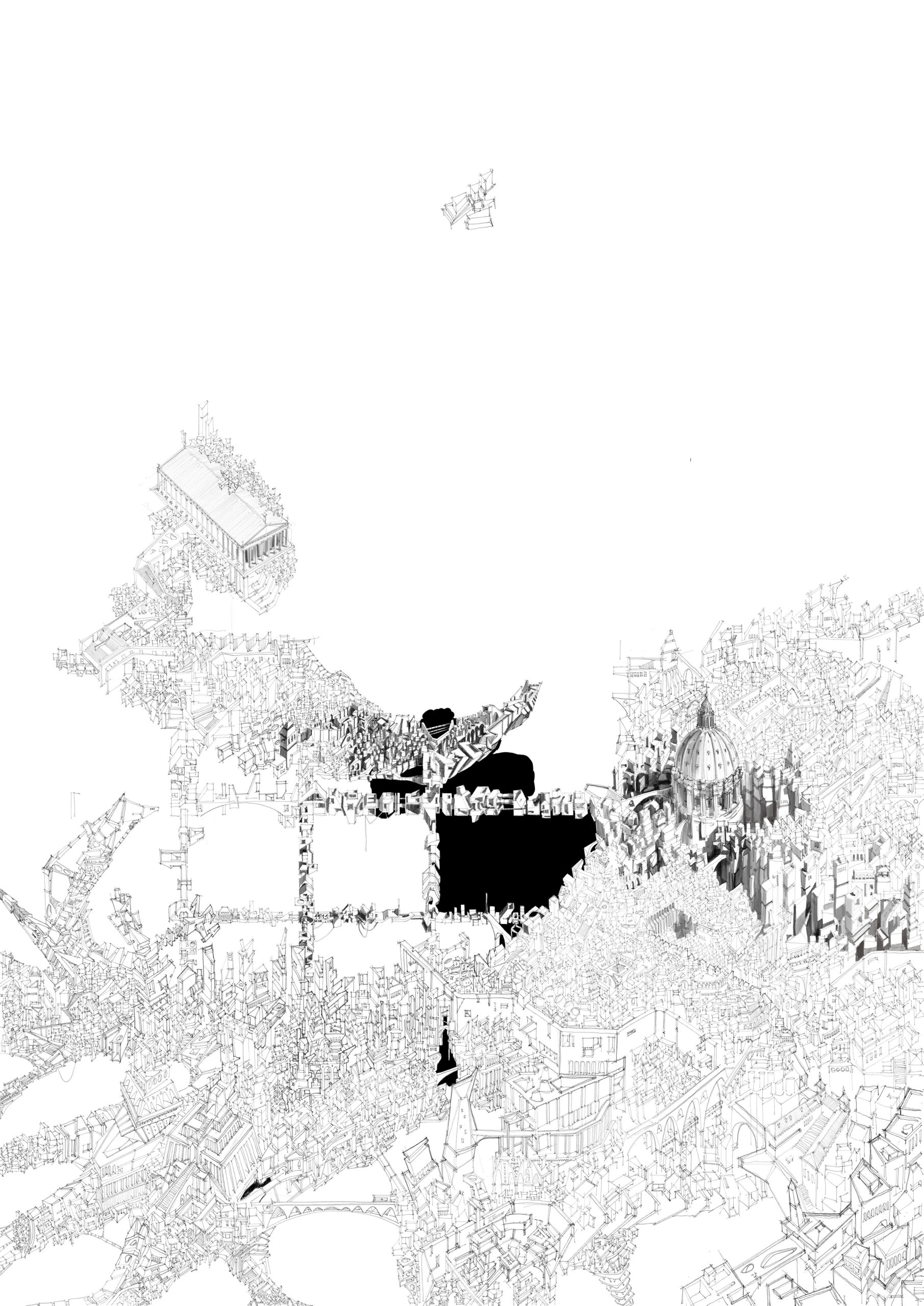

Process image testing the figure ground relationship.

For your piece, why did you choose that specific illustration technique and format?

The original format is an A0, I prefer to stick to the standard formats we use in projects, A0, A1 and so on. I am used to their proportions as I am confident with their scale and the level of detail that’s more suitable to their dimensions. It might be cliché to quote Le Corbusier but nevertheless I will: “Architecture is the learned game, correct and magnificent, of forms assembled in the light”. If Architecture could be paraphrased as such, why not my drawings?

I wanted my drawing to have strong impact and a presence — similar to a medieval monastery laying on the rocks and under the mediterranean sun of Mount Atos or the enormous Imperial Space ships from Star Wars or the breathtaking atmospheres of the urban sceneries drawn by Katsuhiro Otomo in Akira. So, black and white, light and shadows, clearly defined masses are the means used. I am very used to drawing with technical pens and markers, so when I switch to a tablet — as in this case — I stick almost entirely to these tools.

By the way, I think that architecture and even a drawing are more than the above definition, but for that we need to go beyond technique and enter the domain of the subject and narrative.

HF: Do you have any other architectural drawings as conceptual as this?

All of them are in a way. I like to categorize my drawings into two types: first, there are the more abstract works, more detached to the sensorial reality materialized through a creative process coming from within, similar to the process named by the surrealist automatisms. “Vortex” falls into this category.

Then, my other sketches are fast and quite rough. They are representations of captured moments of places, mostly unusual urban situations. Even these drawings aren’t just a simple mimesis of the reality, they divert from it depending on my personal perception and intention. So, a building might be taller and an alley narrower in my sketch; their perspective may be distorted, but despite their ambiguity those sketches might look more real than the actual reality. This second series of drawings are also a sort of mental data recollection of hundreds of elements and signs related to architecture and the city. These will become the vocabulary for the more complex and abstract works.

Process image of adding the shadows (scaled).

How did the process and workflow of creating your drawing compare to traditional architectural drafting?

When I work on an actual project — as most architects do, I guess — I start with a very first sketch outlining the main idea. This usually comes to me after visiting the site, or even before after initially hearing about it and a bit of research. Then, afterwards, in the following days and weeks, other sketches follow defining the main volumetric and spatial features of the piece of architecture to be. This is actually very similar to the way I work on my drawings.

Normally, I “see” my work after I have an interesting discussion; after looking at a news in the media; after reading a certain text; or, after happening to come across a certain place. I would have never created Vortex without reading Derrida reflections on structure and the Center, Foucault’s definition of Panopticism, or without having a discussion few days before starting with a colleague about Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of Smooth and Striated space.

The above cultural environment is the site — the context on which I draft the very first outline, a first level, of the drawing. Then the detailing process starts. It’s like designing a city: you have to draft the streets, squares, buildings and main landmarks that will become the second level of vectors and center of my images. This detailing process is actually more important from the perspective of the viewer. This is because while the general outline (which, in the case of Vortex, is the spiral) catches the attention, the second layer, made of a multitude of details, invites them into the drawing. There they might get lost in those spaces and driven to explore them further. At this point they may even fall in love with it.

What one tip would you give the other participants looking to win next year’s One Drawing Challenge?

Try to learn from the work of others that you value. Understand their content and technical peculiarities, and try to master and remaster them in your own work. Understand what characteristics are yours only and improve and refine them.

The competition-winning final work.

Any further thoughts?

Maybe I could spend some more thoughts on the subject of Vortex. It is about crises that are no longer hypothetically imminent but actually happening. Crises that are local and global. Being an Albanian, I am familiar with crises that are beyond personal. Albania is this small former communist country that during the 90s went through the dramatic passage from socialism to market economy, from dictatorship to a democracy of some sort; that went through severe economic collapses, popular rebellions and several massive emigrations. Despite this, for the last 20 years — similar to the so-called developed countries — we have been living a relatively carefree normality. The troubled recent past seemed distant.

Historiography and fiction alike have accustomed us to believe that between the normality of, let’s say, Friends, and the “normality” of Mad Max Fury there is always an in-between event, a zombie apocalypse or a global nuclear conflict. The pandemic was seen as one of these global-rupture events — a sort of ritual toward another normality, that woke us up and made us aware that reality can be as frightening as fiction, and that history is still being made.

Time flows, things change, present becomes past. One of the things I tried to do with my work is the demystification of this sequential perception of time. We are now consuming the oxygen we are breathing, we are now polluting the water we drink, we are now building over the land that is supposed to feed us. Likely all these things won’t neither last forever or finish suddenly in one event. We are making our future, and if we will get lost in the comfortable and illusory sense of stability of the present, tomorrow won’t be a very bright one. The next Crisis is already unfolding.

Sign up to be informed when the next One Drawing Challenge competition opens for submissions. Be sure to check out the rest of this year’s extraordinary Winners and Commended Entries.