Named after “segja,” the Icelandic word for “tale,” Saga is a collective of five young architects: Pierre Y. Guérin, Camille Sablé, Anastasia Rohaut, Simon Galland and Sylvain Guitard. The initiative started in 2014, guided by the mission to instill new dynamics within environments and communities through precise actions, experiments and architectural interventions. In the following interview, Saga opens up to Architizer and tells the story of architecture as a strong transformative act for communities that are often overlooked. In the wake of Alejandro Aravena winning the 2016 Pritzker Prize, Collectif Saga demonstrates a very simple, yet heartfelt, drive toward humanitarian architecture, highlighting the power of collaborative work and what it can achieve for communities around the world.

Architizer: Collectif Saga describes itself as wanting “to work in places that usually aren’t predilection fields for architects.” How do you select those places that you want to work in, physical and theoretical?

Collectif Saga: The ideology behind Saga is based on a different approach to the practice of architecture. Our primary objective is to operate in locations that are not considered a priority within traditional development plans and architecture orders, such as townships in South Africa or the suburban residential areas of France. However, these are important sites of transformation in which we can develop different ways of building, of living. Saga bases its interventions on local initiatives as a means to facilitate the growth and development of communities. We use our expertise as architects to serve the needs of the local populations and contribute to the revivals of areas that are often viewed as underdeveloped and stagnant. We are committed to active engagement in terms of identifying and funding projects instead of passively waiting for third parties to initiate the development process.

As individuals, we strive to expand our horizons by exposing ourselves to cultures outside the boundaries of our hometown or country, attempting to understand the distinct norms and values that shape these communities. Our experience working in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, demonstrated how our inherent naivete as foreigners became an asset in order to dismantle existing local prejudices and achieve our construction projects.

The project at Silindokuhle Preschool is a great demonstration of working with locally sourced and upcycled materials. What was the process for identifying and sourcing the materials you wanted for this project?

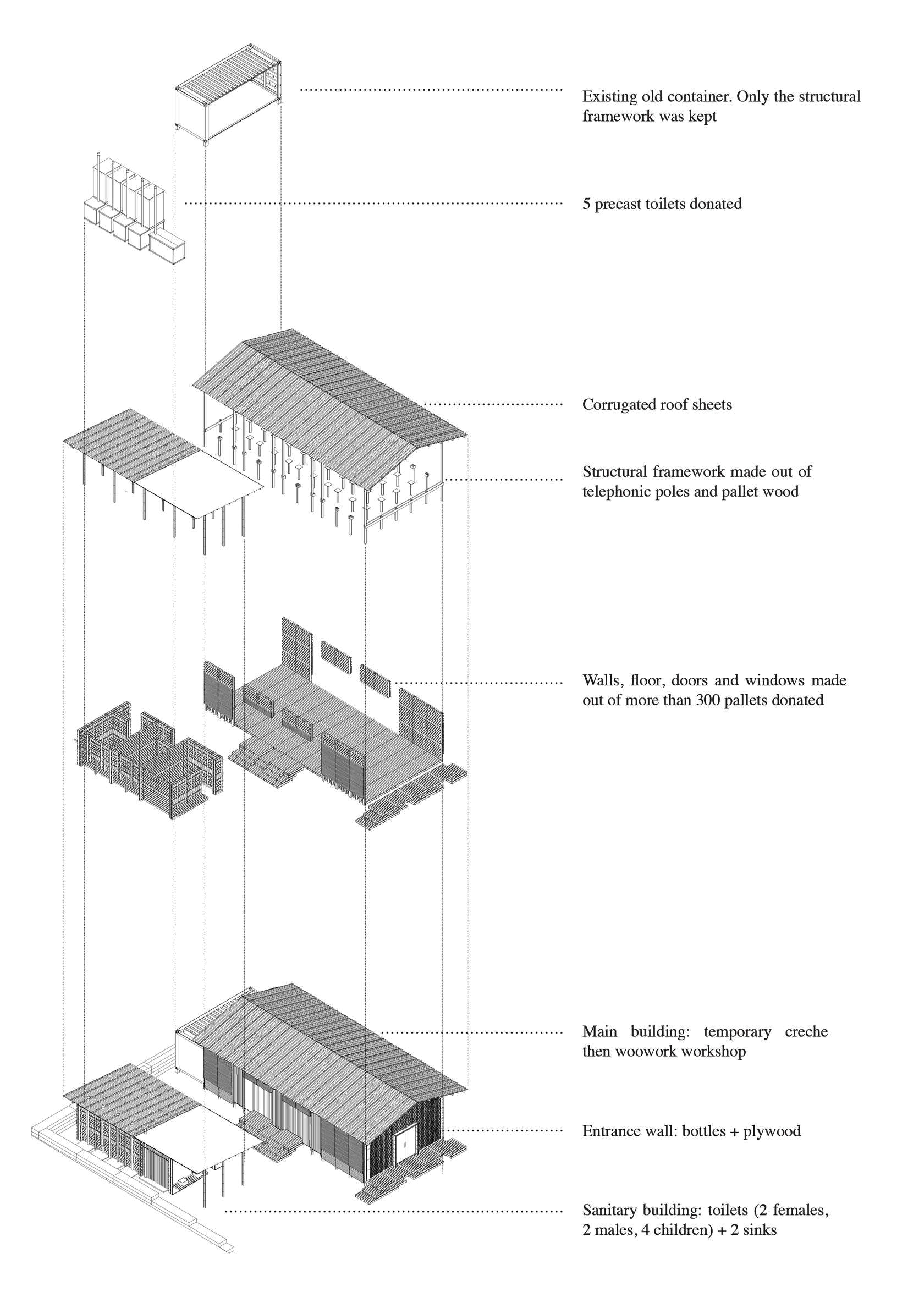

When we initially assessed the informal settlement of Joe Slovo township (where the Silindokuhle Preschool is situated), we noted that all the surrounding structures were built from locally sourced and secondhand materials. The feasibility of these structures was reinforced by the use of recycled waste materials during the construction process. Over time, the inhabitants of Joe Slovo township have been able to build churches, furniture, houses, bars and shops through the use of a few corrugated sheets and pallet planks, and, while these structures are extremely fragile and often need to be rebuilt yearly, this construction system allows for a sense of flexibility within the community. For example, for each significant family event (birth, wedding, death, etc.) the house is remodeled in order to satisfy the family’s changing needs.

The primary challenge of the project was to design a building that could fit in this environment while being durable in the long-term. It was essential that the inhabitants could oversee the maintenance of the building themselves, so it was absolutely necessary to source materials that the community could easily obtain with their limited resources.

We spent a significant amount of time scouring the city in order to search for materials. Port Elizabeth is the perfect city to conduct a project of this kind because it is near massive industrial areas, so materials like bottles, pallets, crushed glass and tires are relatively easy to obtain, as they are often considered waste. The neighboring industrial companies were happy to provide us with their “waste materials” as it saved them from having to utilize alternative methods of disposal. The next challenge came up when we had to think of a way to formulate techniques whereby these waste materials could be transformed into effective building components. For example, we wanted to fit sliding doors on the side of the building, but our restricted budget could not allow this. After analyzing the sliding door system, we discovered that its function could be replicated by using two skateboards on a metallic rail.

In what ways do you consider contextual trends and traditions when developing a project concept or activity for the community?

Our approach depends on the active participation of community members throughout the construction and development process. The execution of a project involves meeting with members of the community and determining the best design and construction program for the proposed building. Working with local architects and craftsmen, we identify local construction techniques to implement them during the building process.

When you first arrived in Port Elizabeth and proposed your projects, what was the reaction of the community?

In Port Elizabeth, we joined local community member Patricia N. Piyani, who had built a small crèche using funds from her own pocket in order to overcome the lack of services within her community. Piyani’s project started a few years back and gained momentum with the help of Love Story, a local NGO. Later, a partnership was established between Love Story and Indalo World, the NPO founded by local architect and academic researcher Kevin Kimwelle, and the two organizations aimed to expand on Piyani’s original idea. Saga joined these two organizations in realizing the first phase, completed last year. Phase 2 is planned for 2016 and phase 3 for 2017.

Because the project originated from a local initiative, it boded well for its overall appropriation by the community. An enthusiastic group of residents offered their assistance to us on a regular basis and the construction site remained open to the public, contributing to an avid welcoming of the new facility. The construction site quickly became an interactive area for the locals due to the lack of alternative public facilities to meet together, and we embraced this opportunity by organizing public events throughout the construction process as a means of strengthening our relationship with the community.

How is your organization funded and operated? Do you have a long-term vision of growth?

Currently, Saga is predominantly funded via public and private grants and sponsorships. We launched a successful crowdfunding platform last year and are looking to generate funding from a wider range of sources in the long term. To do so, we are involved in external activities that generate income, like smaller scale architecture projects as well as graphic design projects and a published book about our experience in Port Elizabeth.

In what ways do you stay in touch with completed projects and measure their impacts?

Since the Silindokuhle Preschool project is planned over four phases, we are returning to Port Elizabeth in a few months to begin the second phase. This project has facilitated a collaborative effort between the various organizations involved (both local and international), so that each institution has a clearly defined role. Indalo World, the local NPO, is tasked with overseeing the evolution of the project, and they update us through weekly reports. Community-based projects cannot be executed without establishing a strong partnership with local organizations that are already entrenched within the domestic context and the community.

The appropriation process that was initiated during the construction process served as the primary measure of its impact. By creating an open construction site and organizing various public events during the construction period, a strong sense of ownership was established within the community. The construction site was utilized both day and night as a meeting place and recreational space for community members. The pragmatic use of the incomplete building by the local residents therefore indicated that the project would have a positive social impact.

What advice would you give to architecture students today? What led you to go in this unique direction after architecture school?

What really pushed us in the direction of Saga was the desire to physically act in this world that is ours. We refuse to passively accept the current state of the world, the current state of global architectural production, which often satisfies purely economic objectives. We long to create — to form ideas in our minds and build them with our hands and with the people they concern.

During the course of our studies, we were lucky to gain practical experience at various studios where we were introduced to both sociological and constructive approaches to architecture. Once graduated, we tried and combined both approaches to see where it would lead. When we were offered the opportunity to work in Port Elizabeth, we took a chance. Curiosity, but also the idea of making a difference — however small — was something we had all been harboring for the duration of our studies.

While we only left school a year ago, we can say that current architecture students should dare to act — either in their local surroundings or beyond. The response when one gets out of their comfort zone is certain to exceed their expectations. Passivity is maybe the primary reason why our cities become dysfunctional. As architects, we must address this issue and use our combined skills and knowledge to harness the existing dynamics of the urban environment, making new and better connections between its individual components. Architecture is in fact a game, a beautiful game, in which the result can be a strong transformative social act.