David Staczek is a principal at ZGF. Staczek’s 26 years of design experience have focused on healthcare facilities while being informed by a broad portfolio of work, from office buildings and financial institutions, to pedestrian bridges and multimodal centers.

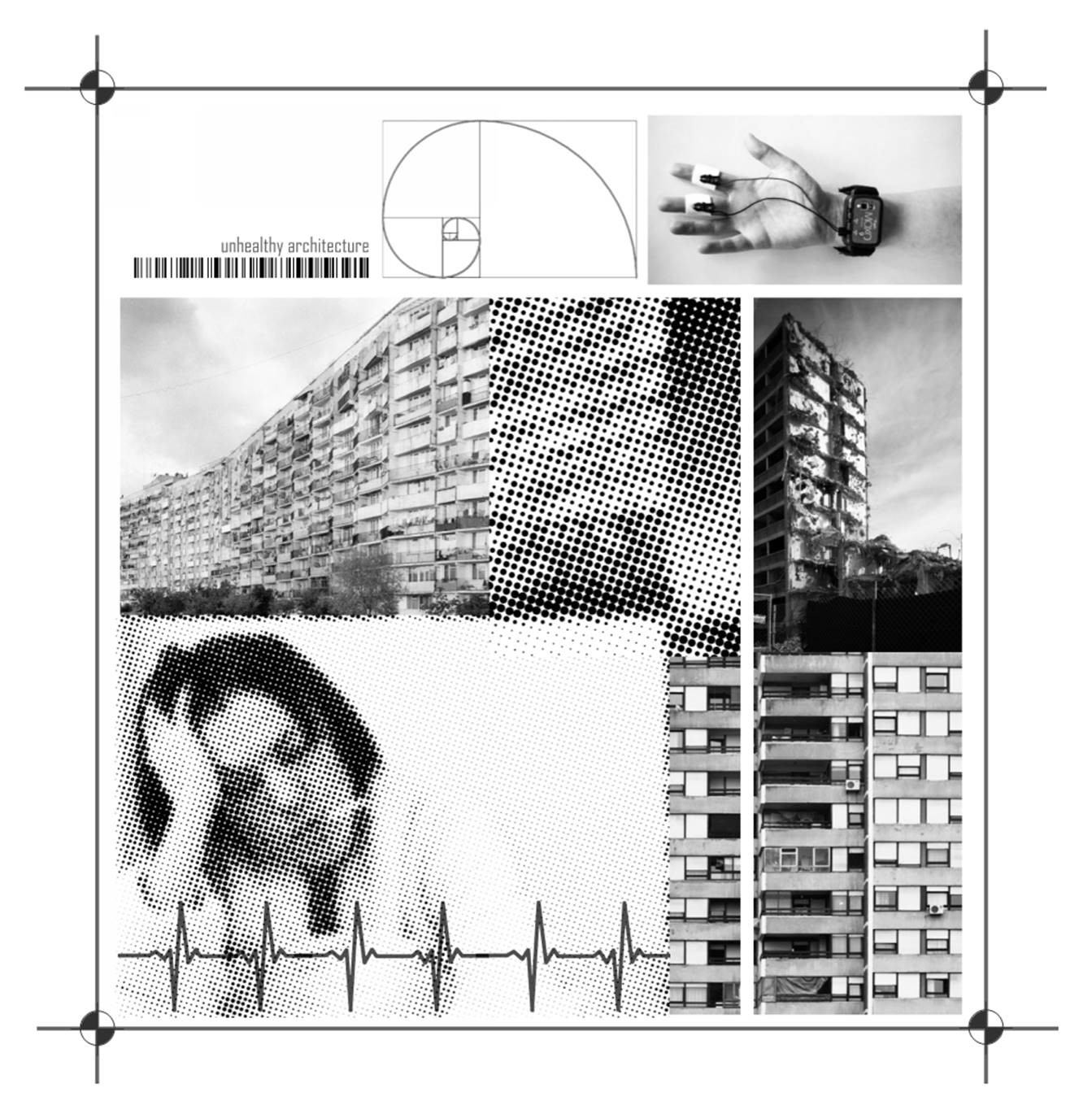

Is bad architecture harmful to our health?

This is a rather big and bold question. In order to answer, we first need to agree that architecture, planning and design have power.

Architecture, planning and design have the power to impact our mood, affect patient outcomes in medical facilities, enhance or detract from our performance and focus, and move the needle on the bottom line.

Now that we all agree that design and architecture can impact how we live, let’s dive deeper into the ways – good and bad – that it affects our health.

Let’s begin with a quick primer of what qualifies as good architecture and good design. Good architecture or design successfully incorporates elements of urban planning, landscape design, sustainable design, interior design and environmental graphics. Good architecture and design give us positive distractions. Roman architect Vitruvius, in his treatise on architecture, told us that buildings “should delight people and raise their spirits.” Recall where you were when you first experienced a space that moved you, whether it was Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Fallingwater House or the Eiffel Tower. You likely experienced a moment of discovery and surprise. That is good design.

Without positive distraction, variety, and a harmonious blending of the elements of good architecture, buildings and structures will start slipping into the “bad architecture zone.” The “bad architecture zone” is not a place we want anyone to go to, yet we see and experience examples all around us.

Here, we need to define what constitutes “bad architecture.” Is a space doing harm? If so, we should determine if the design is directly or indirectly causing the harm. Directly harmful architecture is a category of its own with examples scattered across the globe, from buildings that melt cars with a “death ray” caused by reflective glass to unsound planning that collapses on occupants.

London’s Walkie Talkie building, left; AP Photo/Frank Augstein

I want to focus on architecture and design that causes harm indirectly. The indirect effects of poor design are by far the most common. We can all probably recall a building that evokes feelings of discomfort or disorientation, even if we can’t put our finger on why. There are spaces that force procrastination and outright contempt. Think about how you avoid certain paths when driving through town because of traffic or potholes. We tend to do the same things to avoid poorly designed spaces – think dark alleys, basement offices or our least favorite conference rooms.

Bad architecture can cause literal and figurative headaches. One way is through the introduction of stressful visual landscapes. Dead-end corridors, low ceilings, lack of windows and restricted access to views can lead to disorientation. These design elements can leave occupants asking stress-inducing questions like, ‘where is the front door?’ and ‘how do I get out of here?’

Blind corners and poor lighting conditions (both too bright or too dark) can throw off the body’s natural circadian rhythms, impacting everything from healing in a healthcare environment to productivity in the workplace. When spaces, places and buildings are unpleasant and we dread, or even avoid going there, it can cause our health to deteriorate. We may abandon trips to the doctor, dentist, therapist, gym or other health-related visits if they are an in an unpleasant environment.

Arizona Cancer Center by ZGF Architects: Scale, proportion balance, natural materials, contrast and balance. Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing Photographers

As designers and architects, how can we fix this? How can we change the conversation to explore how good architecture make us healthier?

I’d like to suggest a Hippocratic oath for design, where one of the first design criteria for every project would be to do no harm to the existing context and surrounding area. If our clients or the brief don’t specifically mention these aspirations, then as designers it is our role to adhere to the oath and aspire for every project to impact the surrounding context in a positive way by responding to the sites scale, materiality, texture and orientation.

Some key characteristics of this oath include:

- Aesthetics: Seek balanced compositions of natural patterns and geometrical proportions. Combine with elements of surprise and delight that can reduce stress and lower heart rate and blood pressure.

- Planning: Consider how the functional layout of spaces can have a positive effect on our health. Design visible and inviting stairs, plan for windows and daylight at the end of corridors for orientation and connection to the rhythms of the day and seasons. Plan buildings and campuses to have safe and inviting pedestrian circulation paths to and from parking areas or mass transit stations to promote more walking.

- Interior Design: Design spaces with a balance of calming simple surfaces and areas of visual interest. Introduce positive distractions including connections to nature, art and comforting materials.

- Discovery and Delight: Ensure design and planning that leads users through the building with spatial clues and architectural wayfinding, not signs.

- Technology: Consider how multi-media display walls, VR, AR and sound controls play a role in personalizing spaces to create a sense of ownership and control. This can lead to a calm and happy occupant.

- Construction: Practice good detailing and smart material selection can eliminate leaks, mold growth, drafts and off gassing resulting in healthier buildings. Following through with these details during construction is just as important.

The best and most promising aspect of these oaths is that we can apply them to all design, everywhere, at any scale. Whether we are leading adaptive reuse projects for suburban shopping malls, transforming car factories, or redesigning a local restaurant, every space matters. Good design practices can increase our quality of life.

Federal Center South by ZGF Architects Fed center south: Natural materials, visible stairs, natural daylight, contrast and balance. © Benjamin Benschneider

We know intuitively (and through plenty of research) that bad architecture and bad design can negatively affect us mentally and physically. That’s why we need to focus our collective talents on the opposite equation – good design that make us healthier! We must design buildings and spaces with connections to nature, balanced compositions, natural proportions and thoughtful planning that promotes a healthy lifestyle.

We must provide views, access to outdoor spaces, visible and open stairs, and environments and materials that clean and filter the air. Further, we need to design comfortable environments with the ability to flex and adapt to lighting conditions, weather and the changing of the seasons. It’s through this approach – to do no harm – that we can raise the collective design bar.