In 2012, Phaidon released Concrete, a stunning photo book put together by William Hall that looked at 180 concrete buildings. The book spanned millennia, covering the best of concrete architecture from the time of Ancient Romans to the present day, and earned praise from writers like Architizer’s Paul Keskeys, who called it a “veritable treasure trove.” The publication also earned a place of pride on the coffee tables of architects around the world.

The original version of this book was quite massive, which may have fit its subject matter but presented a challenge to architecture fans with limited space in their apartments. Luckily, Phaidon reissued the book as a special mini edition. While some of the selections have changed — the authors chose to focus on structures from the past century for this edition — the book remains an inexhaustible source of information and a delight for anyone interested in the most flexible of all building materials.

Concrete opens with a captivating introduction by the artist and writer Leonard Koren, in which he examines concrete from all angles, detailing both the pleasure of concrete and the environmental challenges it presents. Cement production, we learn, accounts for five to seven percent of global CO2 production each year. Moreover, quarrying rocks generates a great deal of air pollution. Are these drawbacks offset by concrete’s extraordinary energy efficiency and durability? On these points, Koren is inconclusive.

“All materials have issues, obvious or latent, relating to their environmental sustainability,” he writes. “In the unlikely event that our civilization one day reaches a consensus that concrete manufacturing and use is an unsustainable practice, so be it. But I suspect this will happen around the same time capitalism is dethroned, consumerism is banished and seeking comfort in material things is perceived as criminal behavior.”

In other words, concrete is here to stay, which is good news for architects looking for a flexible material that can be adapted to their most inventive designs. The following buildings, selected from Phaidon’s book reveal the myriad effects that can only be achieved with concrete.

Images via ArchDaily

1. Jagged Stone

Ibere Carmago Foundation by Alvaro Siza, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2003

Alvaro Siza’s building for the Ibere Carmago Foundation in Porto Alegre, Brazil speaks to concrete’s origins in limestone. The structure — which features ramped circulation that emanates from the façade — looks like a rock that has been carved into, an effect that is enhanced by the building’s pleasing off-white hue.

Images via ArchDaily

2. Solid Mass

Casa da Música by OMA, Porto, Portugal, 2005

Rem Koolhaas’s Casa de Musica in Porto, Portugal is described as resembling a “spaceship.” The architects describe the form of their building as an attempt to embrace the conventional “shoebox” form of concert halls that architects have tried frantically to escape for the past 30 years. Rather than disguising the building’s boxiness, OMA focused on making it appear approachable to pedestrians in the public square outside. They add that the white concrete material “remains solid and believable in an age of too many icons.” Architects throughout the centuries have valued concrete for its ability to stand on its own without much adornment.

Images via RibaJ

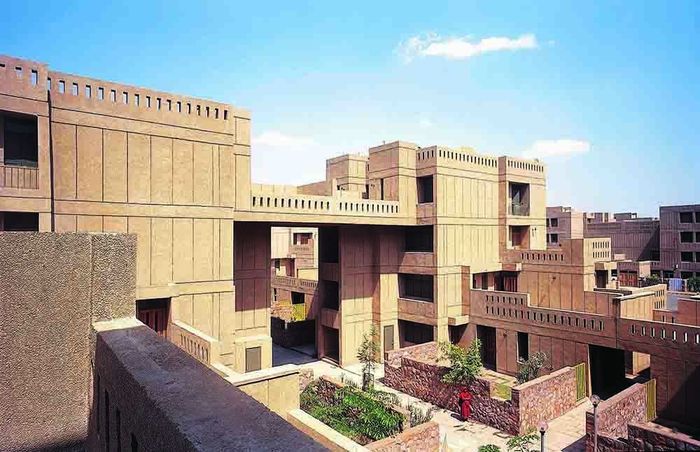

3. Terraced Village

Asian Games Village by Raj Rewal, New Dehli, India, 1982

The village Raj Rewal created for the 1982 Asian Games is a massive, integrative terraced structure that was designed to resemble traditional Indian villages. In doing this, writes William Hull, Rewal rejected the “Modernist approach of open park and high-rise structure.” Games were played in the numerous courtyard spaces that were nestled into the overall scheme.

4. Delicate Folds

Vodafone Headquarters Building by Barbosa & Guimarães, Porto, Portugal, 2008

Barbosa & Guimarães’s Vodafone Headquarters in Porto, Portugal resembles a Japanese paper lantern. It shows how, with the right contouring, a concrete building that produce an effect that is anything but “heavy.”

5. Subtle Curves

Guangzhou Opera House by Zaha Hadid Architects, Guangzhao, China, 2010

The Guangzhou Opera House, like many of Zaha Hadid’s later buildings, is a computer generated fantasy come to life. The complex consists of two “boulders” that, with their softly contoured edges, resemble the ornamental rocks shaped by natural erosion that have inspired Chinese artists for centuries. The tessellated concrete, glass and steel skin of the structure frames a freestanding concrete auditorium. Nothing about this masterpiece — from its complex program to its flowing lines — would be possible without the pliability of concrete.

Image via Wikipedia

6. Tiered Cubes

Hyakudenen by Tadao Ando, Awaji, Japan, 1995

Tadao Ando’s Hyakudanen, or “hundred stepped gardens,” consists of one hundred square flower plots that ascend in the manner of an Aztec temple. The simplicity and durability of the raw concrete surfaces allow the gardens to take center stage.

Images via ArcDog

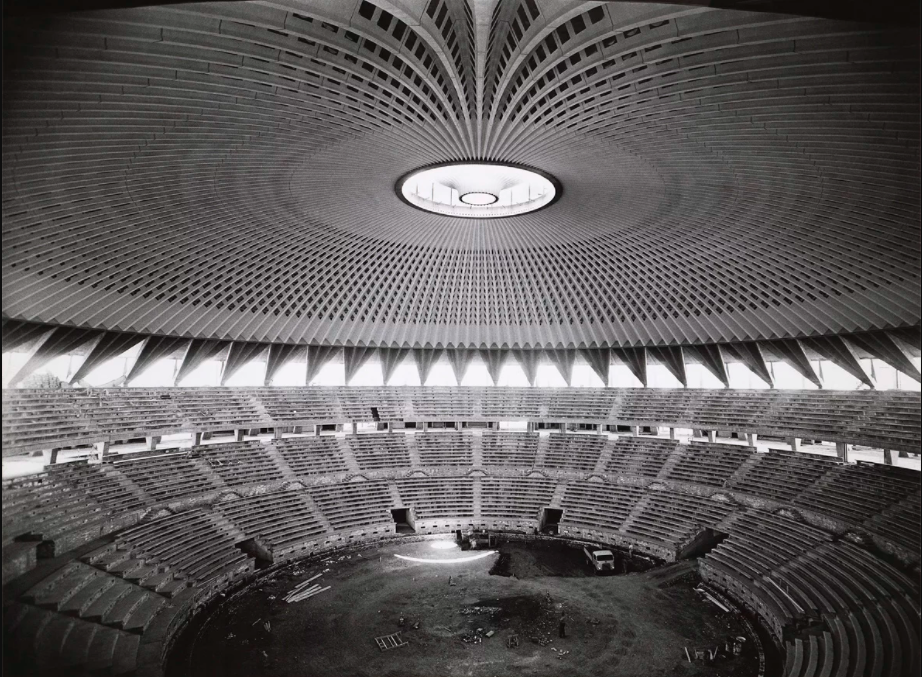

7. Radiant Buttressing

Palazetto dello Sport by Annibale Vitellozzi with engineering by Pier Luigi Nervi, Rome, Italy, 1957

Pier Luigi Nervi was sometimes called the “Great Italian God of Concrete.” The appellation is fitting: there is something of the divinity in the ceiling he engineered for the Palazetto dello Sport, a Roman basketball stadium created for the 1960 Olympics. He even drew on church architecture, utilizing concrete flying buttresses to brace the stunning ribbed concrete dome, which consists of 1,620 prefabricated components.

Want see more outstanding concrete forms? Check out Phaidon’s mini format edition of Concrete.

Casa Da Musica

Casa Da Musica  Guangzhou Opera House

Guangzhou Opera House