Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Stucco is a funny material. On one extreme, it’s the stuff of pure material abstraction. When finished at its smoothest and whitest, it’s the face of modernist simplicity. It’s barely there. On the other extreme, it’s intensely tactile. Rough and grainy, it calls to mind the windblasted deserts of the American Southwest. It’s physical; elemental, even. And it can be a lot of stuff in between.

Le Corbusier’s Ville Savoye has a white stucco exterior; image via Medium.

One of the major appeals of stucco is its versatility. It can take any color and adapt to any shape, from flat boxes to doubly curved fantasias.

What makes stucco a little tricky is that it is mixed and installed on-site. It’s not produced in a factory under carefully controlled settings; it’s made in the field where anything can happen, and architects have to rely on trusted contractors. Contractors will have their own preferences and experience working with various mixes and finishes that depend on local conditions and availability.

© Diego Opazo

Casa Balint designed by Fran Silvestre Arquitectos

We talked to Mark Fowler, Executive Director of the Stucco Manufacturers Association (SMA), about what architects need to know when specifying stucco.

His advice was to “stay with established standards. Many architects make the mistake to add items that are either not appropriate or incompatible, which adds costs by wasting time on RFIs or worse, systems that fail.” Contractors and manufacturers can talk you through what is necessary for the specific approach you are taking.

Fowler’s advice was clear: “Listen to the pros and find someone you can trust. Stucco has more variables than almost any other assembly.”

Maggie’s West London Centre by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners; image via ArchDaily

So what is stucco, anyway? Historically, it was the same material as plaster. In some languages, there is still only one word that covers both materials. Today, plaster is mainly used inside, and stucco out.

Stucco siding is a mixture of Portland cement, sand and water. It’s not radically different from concrete. It is applied in a combination of layers with a standard base coat and a refined finish coat. Finish coats can include small pebbles to add texture or be made with acrylic for more color options. Additional coatings can be added to protect or restore the surface.

We’re going to break down the basics below, but Fowler advised reaching out to the SMA or an experienced contractor for more information on what would be appropriate for your area and installation. “The SMA is here to help architects,” he said. “Specifying an SMA-registered contractor is a good start to a quality stucco job.” Although stucco can be used anywhere, its installation can be a specialty skill, and it is best to get someone who knows what they’re doing.

Contractors will be used to working with certain mixtures and products, so if you are tied to a certain finish or appearance, make sure that your contractor is experienced with it. If you are flexible, follow an experienced contractor’s lead. Fowler put it this way:

“I always tell architects to think of a race car driver. If a driver has won many races with a Porsche, why would you force him to drive the next race with a Ferrari? He does not know or understand this car. The best chance to win is let him drive what he knows. Of course, it must be ASTM- or ICC-approved. Do not let them make their car.”

VitraHaus by Herzog & de Meuron

Read on to get a good base:

One, Two or Three Coats?

Stucco can be applied in one, two or three coats. Which one you choose largely depends on your wall construction, but one- and three-coat systems are the most common.

One Coat

One of the main trade-offs to one-coat assemblies is that one-coat stucco systems are proprietary. Special products must be used, and installation must follow the manufacturers’ instructions. Two- and three-coat stucco systems are generic assemblies, meaning that contractors and designers can use, mix and apply their own products how they like.

One-coat stucco has been applied over rigid foam backing for decades, but this is not exactly the same as EIFS (Exterior Insulation and Finish System), a product that is popular and will be discussed in another article.

Two Coats

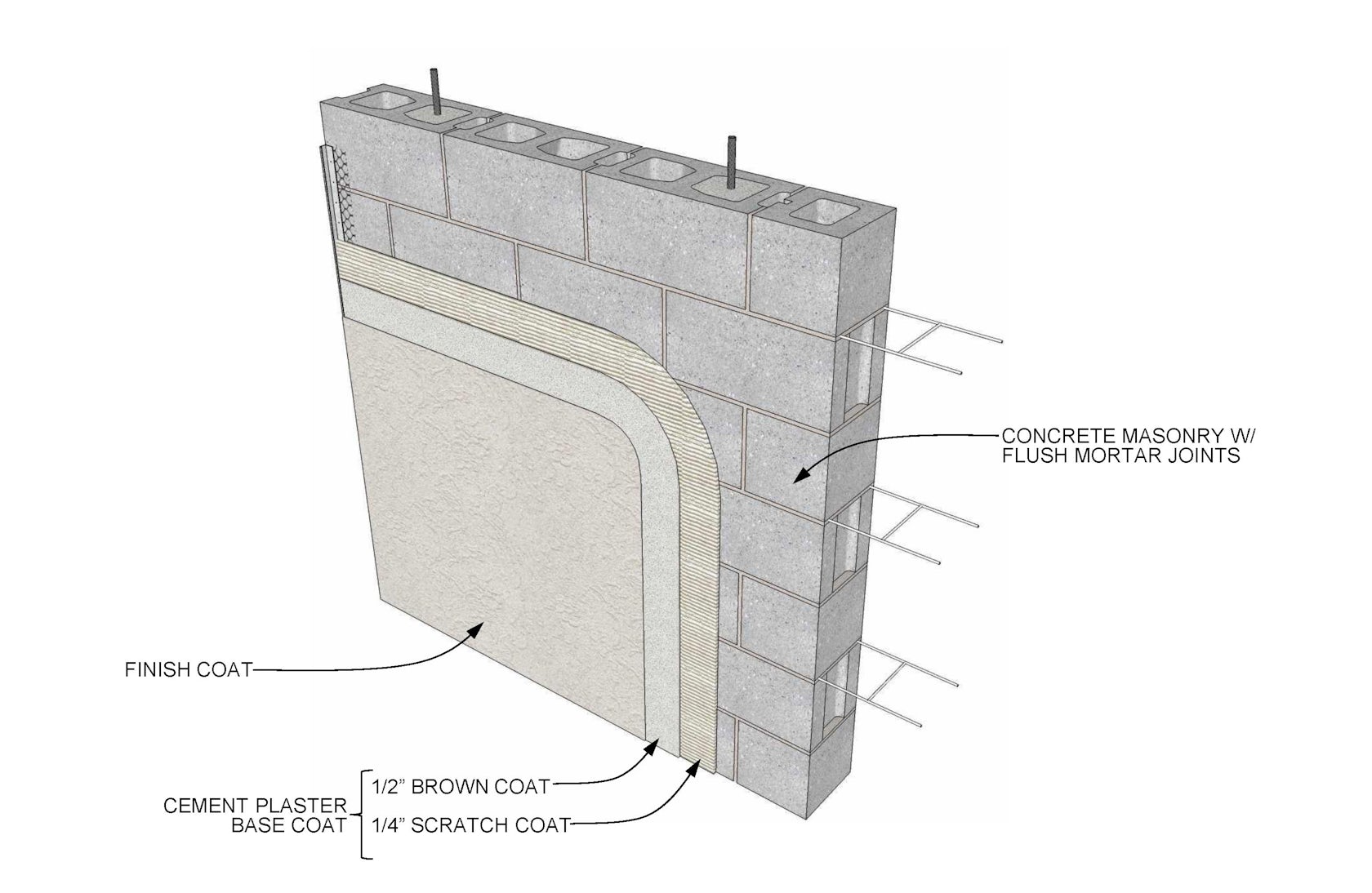

Two-coat assemblies are applied on masonry or concrete walls. This application is most common in Europe, where it has been used for centuries. The stucco should be applied directly to the masonry surface without any vapor barrier in between. “Today, too many think we need to add a building paper between masonry and stucco. It generally turns out a disaster,” Fowler said.

The two coats are the base coat that adheres to the masonry wall and the finish coat that faces the exterior.

Two-coat assembly diagram; image via International Masonry Institute

Hairline cracks will generally develop at some point over the lifetime of a two-coat stucco system, but because of excess calcium and hydroxide in the mixture, these cracks can self-heal. Water mixes with those chemicals to patch minor flaws. Even with the threat of small cracks, the water that could pass through is not enough to threaten the concrete base.

The thickness of two-coat assemblies can vary. According to the SMA:

“The thickness of the cement depends greatly on the substrate’s porosity and flatness. Thickness of application can range from an 1/8-inch skim coat to a 5/8-inch-thick cement base. Any applications exceeding 5/8 inch would generally require a lath be installed to carrier the weight.”

A lath is a wood or metal mesh backing that adds support to stucco.

The SMA added the following tips:

- It is generally recommended that concrete substrates only have skim coats.

- Joints of masonry substrates should be struck-flush.

- Bonding agents made for concrete may be used to ensure adequate bond.

- Expansion/control joints in the substrate shall be honored.

- Control joints may exceed the 144-square-feet rule used for frame construction stucco.

- Weep screeds are not required.

Three Coats

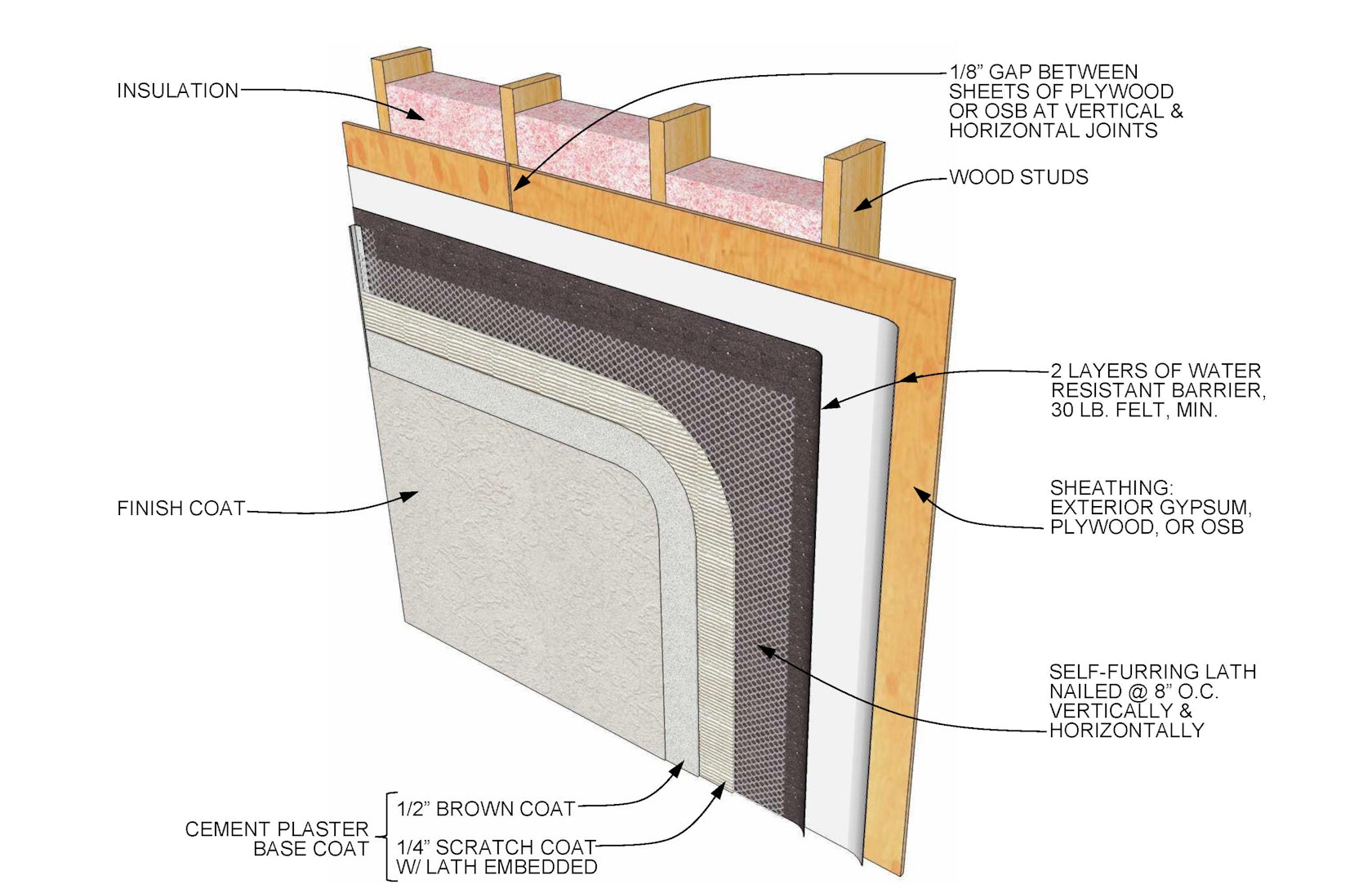

Three-coat assemblies are recommended for timber-framed walls. The three-coat process was developed when stucco came to North America, where timber frame construction is common.

American builders realized that the small amount of moisture that can pass through a two-coat system is enough to damage the extremely water-sensitive wood beneath. According to the SMA, “Cement plaster is absorptive. While it should not be considered waterproof, it equally should not be considered porous.” They add: “Countless tests have verified cement plaster is highly water-resistant.” Fowler said, “Stucco over framing is a weep or concealed barrier assembly. This means a building paper or house wrap [should be used] under the stucco on all framed walls.” Because the stucco will absorb water, it can also drain water at its base and needs to be separated from damp soil. The SMA says that “a weep screed is required over framed walls to allow incidental moisture to escape.”

Three-coat assembly diagram; image via International Masonry Institute

The third coat comes from the addition of a rigid backing layer that two-coat assemblies don’t need because they are a solid masonry substrate. All three-coat systems require a lath backing over a water-resistant barrier (WRB). The layer applied to the lath is called the scratch coat, which is covered by the brown coat, with the finish coat on top.

The SMA added the following tips:

- Two-layers WRB are to be used over wood-based sheathings.

- A lamina over the base coat can reduce or eliminate the need for control joints.

- A 7/8-inch cement plaster provides a one-hour fire-rated membrane on walls with framing spaced no more than 24 inches on center and ceilings with joists spaced no more than 16 inches on center.

Texture

Stucco can be finished in a variety of textures. While the choice is a matter of taste, some of them are more labor intensive for your contractors and have trade-offs.

Smooth

Smooth finish; image via The Stucco Guy

“This is a popular trend, and traditionally stucco contractors hate this,” Fowler said. “Smooth finish tends to crack a little more, and [the cracks] show up a lot more due to the smooth texture.” If you are interested in a smooth finish, make sure you find an experienced contractor who is comfortable doing it. Fowler said that new techniques are making a smooth finish easier to achieve and maintain. “Fortunately, we have a new method that really works well. It is a crack suppression system. After the brown coat, a fiber-reinforced lamina is applied, then a smooth cement or acrylic finish.”

Cat Face, Dash/Pebble-Dash/Roughcast, Lace

Cat Face finish; image via The Stucco Guy; dash/pebble-dash/roughcast finish; image via Wikipedia (rjp); lace finish; image via The Stucco Guy

There are many varieties of more textured stucco finishes. Cat Face stucco is smooth with periodic inclusions; dash stucco has exposed aggregate on its surface; lace is somewhat smoothed for a varied finish.

Float/Sand, Worm, Mission

Float/Sand finish; image via Hughen Plastering; worm finish; image via Cross Country Supply; mission finish; image via Hughen Plastering

“Sand” finish is common and popular for its forgiving camouflage; “worm” is stylized with longer marks; “mission” imitates rougher adobe construction of the American Southwest.

Color

Blue Cube by StudioMilani; photos by Paola De Pietri courtesy StudioMilani

Stucco finish coats can be produced in almost any color that you have in mind. Acrylic finish coats have more color options than cement finish coats, and both can be used on top of any cementitious base coat. Acrylic finish coats tend to be more expensive than cement finish coats.

Joints

Large walls of stucco will require control and expansion joints. “Control joints and one piece trim accessories are used for minor movement. Generally, [they are] 1/4 inch or less and in one direction only,” Fowler said. “Expansion joints are two-piece accessories the allow for greater movement and function in more than one direction.”

Rain Screen

It is possible to use stucco as a rain screen, which technically means that there is “a measurable cavity for air and water to move freely behind the stucco,” Fowler said. “This is challenging and costly to add. It is really only recommended for regions in very wet climates with few drying days. Most of the country does not need it.” To put it another way, he said, “It is like buying a HumVee; unless you live in an area where you need it … why pay for it?”

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Casa Balint

Casa Balint