The Main Entry Deadline for Architizer's 13th A+Awards is Friday December 6th! This season we're spotlighting the talent of architects who expertly balance global challenges with local needs. Start your entry.

Antoni Gaudí and Zaha Hadid worked in distinct periods of architectural history, each leaving a lasting impact on the field. Despite their different eras, they shared a connection in their embrace of organic, fluid forms, challenging the rigidity and linearity of conventional architecture.

Gaudí, who worked during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was influenced by nature’s geometries. He shaped his extraordinary buildings using catenary arches, hyperbolic paraboloids and fractal patterns. Constructions, such as La Sagrada Família and Casa Batlló, mimic natural forms, creating harmonious spaces that challenged the architectural norms of his time.

Zaha Hadid, a pioneering architect of the 21st century, also sought to break free from conventional architectural forms. Her use of parametric design tools allowed her to create dynamic structures that echo the fluidity and complexity of nature. Buildings like the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan, demonstrate her ability to use parametric design to push the boundaries of architecture.

Gaudí used nature-inspired geometries and craftsmanship, while Hadid used advanced computational algorithms and AI-driven design methods. Their innovative approaches revolutionized how we understand form and space in architecture while showcasing the creative potential of the tools and techniques available in their respective times, inspiring generations of architects.

Challenging Norms

Rooftop of La Pedrera or Casa Milà (1906-1912) by Antoni Gaudí. Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. | Photo by Photo by Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz via Pexels.

Antoni Gaudí’s desire to find a different path in architecture was primarily encouraged by his vision of nature as the ultimate foundation for all creation coupled with his deep spirituality; secondly, his departure from conventional architectural norms was influenced by the evolving cultural landscape at the end of the 19th century and early 20th.

Gaudí was considered a prominent figure of Modernisme — the regional Catalan variant of Art Nouveau, not to be mistaken for Modernism, the broader international movement. Also, during Gaudí’s time, architectural trends such as Neoclassicism, Gothic Revival and Arts and Crafts dominated the cultural and aesthetic landscape. The Industrial Revolution also played a significant role, introducing new materials and building methods that influenced architecture. Gaudí, however, rejected the architectural norms that emphasized classical forms, symmetry and proportions. He viewed them as movements that lacked creativity and didn’t reflect the changing character of society and technological progress.

Unable to find inspiration and motivation in these movements, Gaudí turned to nature. His fascination with nature’s forms and structures, which he studied passionately, led him to develop biomimetic designs, which became his distinctive signature. His connection to nature, rejection of traditional styles and strong spiritual beliefs set him on a path that distinguished him from many of his contemporaries.

en:User:Sandstein, a.k.a. User:TheBernFiles, Vitra fire station (1993), full view, Zaha Hadid, CC BY-SA 3.0

Similarly, Zaha Hadid rejected the rigid, orthogonal forms that shaped much of the 20th-century architectural landscape. She also challenged modernist functionalism and the “form follows function” principle, arguing that this design approach limited aesthetic freedom. Instead, she embraced dynamic and sinuous forms. Hadid demonstrated that architecture could be expressive and functional with her sculptural designs. Her iconic wavy and sharply angular forms are a beacon of creative freedom, challenging the conventions of how buildings can be seen and used.

Hadid has cited natural landscapes, such as rivers, dunes, and geological formations, as a major influence on her work. However, she also drew from avant-garde art movements like Russian Suprematism and Deconstructivism (as anyone familiar with her conceptual design for the Irish Prime Minister’s residence in Dublin can attest). The Vitra Fire Station exemplifies her interest in these movements, with abstract, irregular and fragmented geometries as key design elements showcasing her departure from conventional architecture.

Architectural Organicism: Gaudí and Hadid’s Biomimetic Design Approaches

La Pedrera or Casa Milà by Antoni Gaudí. Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. | Photo by Manuel Torres Garcia via Unsplash.

Gaudí and Hadid explored the creative possibilities of organic shapes and complex geometries through organicism, designing structures that seemingly grew with their environment and evoking organic forms.

Biomimicry or biomimetics, central to Gaudí’s aesthetic and deeply rooted in the natural world, served as both an aesthetic and structural guide. Gaudí saw the curves of plants, the branching of trees, the skeletal structures of animals and shells not just as beautiful but also structurally efficient.

He developed building technology for hyperboloid structures that curve as they extend upwards, mimicking trees or caves, structures that felt as if they had emerged organically from the earth. In the Sagrada Família, Gaudí incorporated tree-like columns and branching structures that reflected natural elements’ structural efficiency and aesthetic qualities. Buildings like Casa Batlló and La Pedrera— also known as Casa Milà — showcase his commitment to natural shapes, where fluid lines and textured surfaces evoke the forms of waves, plants and bones.

Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre by Zaha Hadid Architects. Changsha, China. | Photo by Virgile Simon Bertrand via Architizer.

Hadid’s exploration of biomimicry and organicism differed from Gaudí’s in its reliance on AI-driven design tools, but it is precisely this technology that enabled her to refine her works. Even after her untimely death, the fluidity and dynamism of the architecture constructed by the firm she left behind is distinct; they often resemble natural topographies and flowing waters. Their buildings are deeply organic and at the same time, futuristic. For instance, the wavy forms of the Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre, where fluidity is a defining design element, exemplify her commitment to nature-inspired architecture.

Organicism was, however, not the only focus of Hadid’s designs, but part of a broader architectural vision. Hadid also embraced parametricism to explore movement and dynamism, taking design to a more abstract level.

Organic Architecture: Gaudí’s Handcrafted Models vs. Hadid’s Digital Tools

Antoni Gaudí’s plumb line model for La Sagrada Família. | Photo by Stuart Madeley via Flickr.

While Gaudí relied on manual methods and handcrafted models to explore nature’s organic geometries, Hadid used advanced computational tools to achieve similar results. They both created buildings that evoke a sense of movement and natural growth. Their work demonstrates how organicism and biomimicry can be adapted to different times and technologies, each using nature as a guide to optimize both beauty and functionality in architecture.

Gaudí did not rely exclusively on two-dimensional drafting unlike most of his contemporaries. He experimented with clay, rock, rope and paper to build hanging chain models. This technique allowed him to explore catenary curves to determine the most structurally efficient form without the benefit of digital computation. Through these manual processes, Gaudí created extraordinary structures and his pioneering use of materials like reinforced concrete and iron enabled him to produce structurally groundbreaking forms.

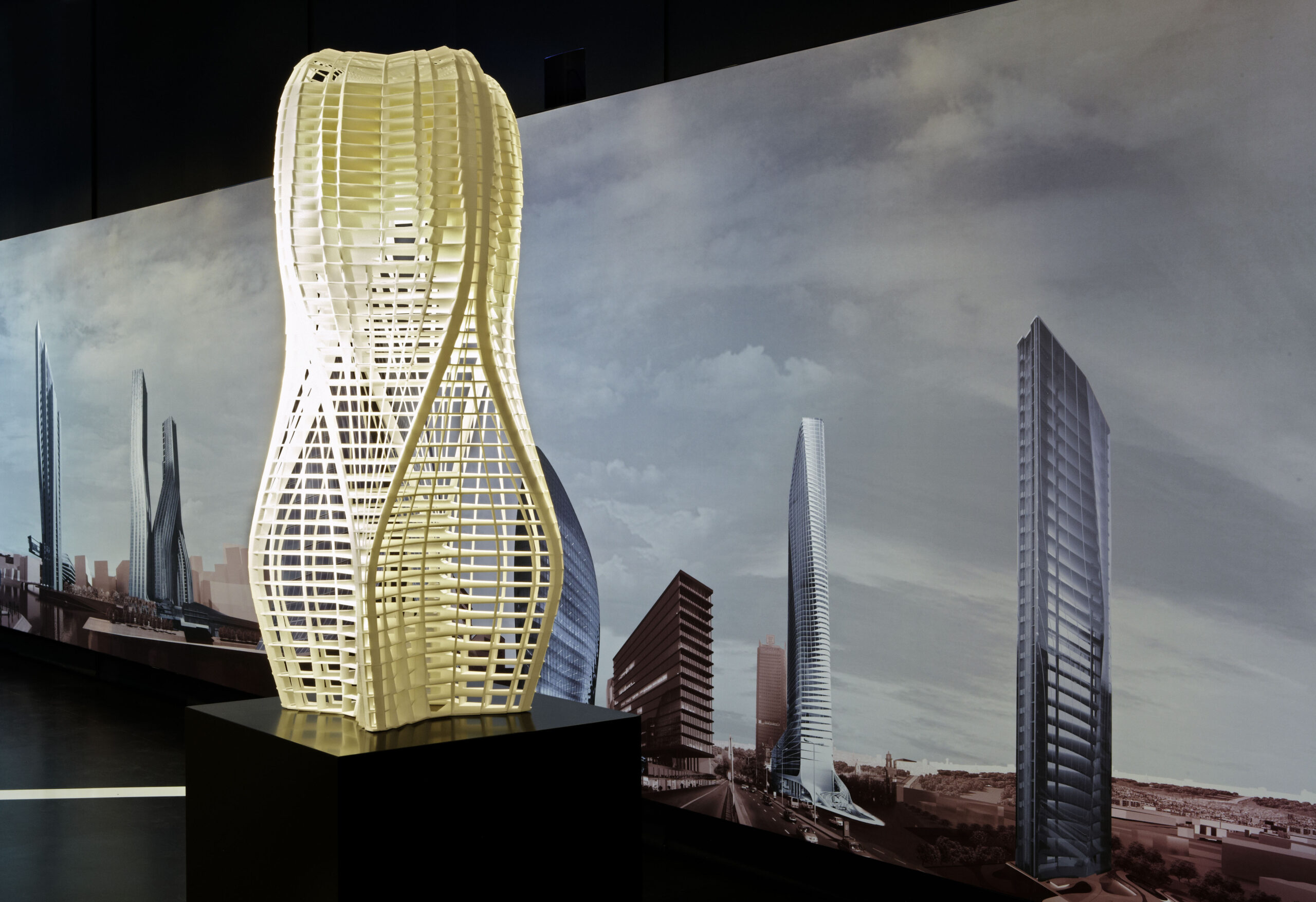

Model by Zaha Hadid Architects for the “Parametric Tower Research” exhibition at The AIT ArchitekturSalon, Cologne, Germany, 2012 | Photo by Forgemind ArchiMedia via Flickr.

Zaha Hadid, by contrast, worked in the digital era, where she leveraged parametric design tools to infuse her architecture with a level of fluidity and dynamism unimaginable in Gaudí’s time. Her sculptural designs relied on optimization algorithms and 3D modeling software. Where Gaudí built physical models to experiment with complex geometries, Hadid used computational software like Rhino and Maya to simulate and iterate on fluid, organic shapes. Her exploration of parametricism, a design approach that allows for the manipulation of multiple variables to optimize form, enabled her to create sharply angular and wave-like structures that dynamically respond to their environment. Hadid’s digital optimization ensured that her forms were visually striking and structurally efficient, much like Gaudí’s gravity-driven catenary curves, but taken to a more abstract and technologically advanced level.

AI-driven Design Tools to Extend Gaudí and Hadid’s Legacies

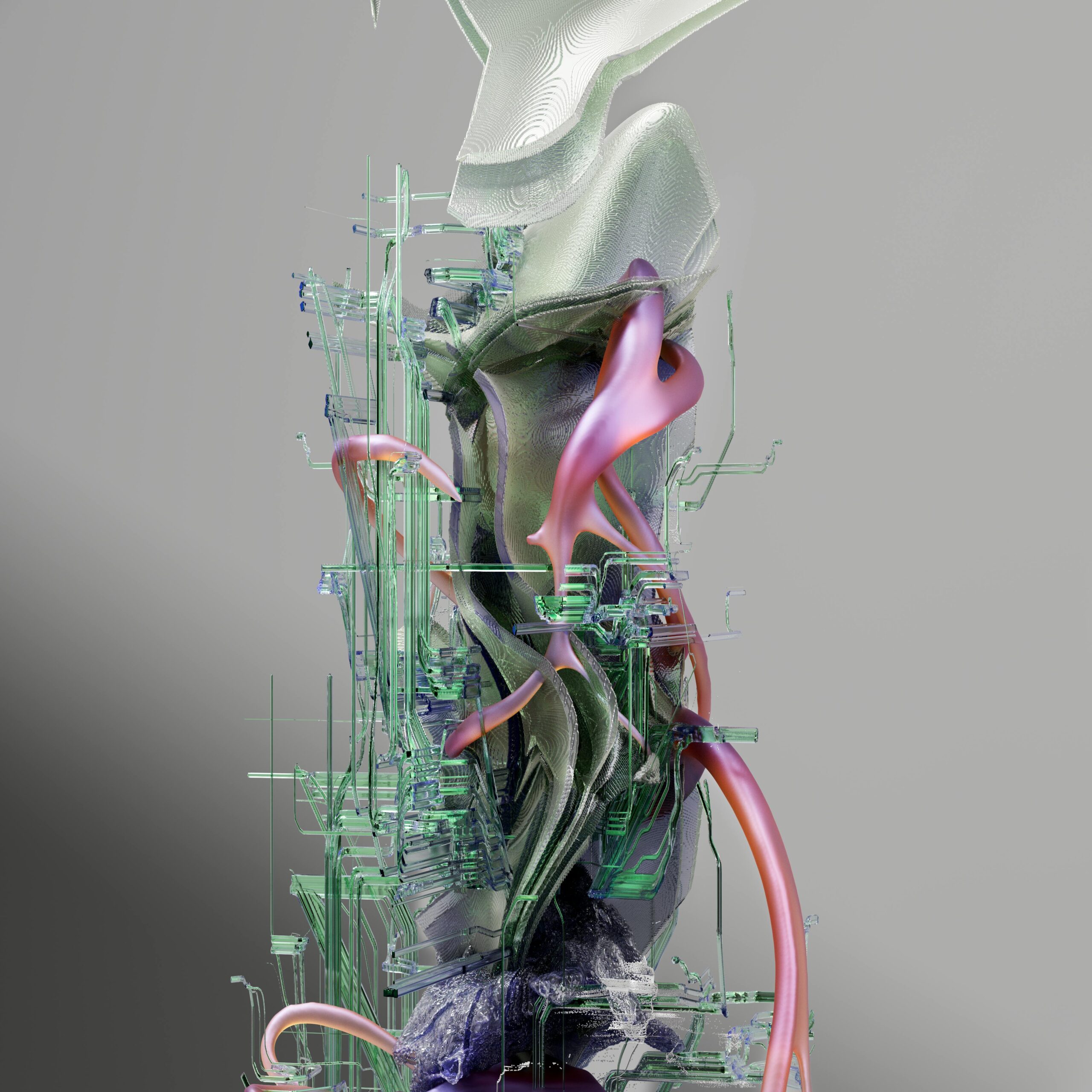

Artist’s illustration using AI. | Image by Google DeepMind via Pexels.

Gaudí, who worked in the pre-digital age, used innovative approaches to geometry and physics that resonate with modern parametric design principles. His complex constructions were groundbreaking for their time. Hadid, on the other hand, used AI-driven design tools to explore and enhance organic principles. Her buildings, characterized by flowing surfaces, would most likely be impossible to create without parametric technology.

As AI continues to evolve, it has the potential to extend Gaudí and Hadid’s legacies, expanding architecture’s creative horizons. However, this raises questions about its broader impact on architectural practice: Will AI democratize design, breaking down barriers or will it reinforce disparities in the field? These disparities could arise from factors such as automation and job displacement, or the need for specialized training and tools that some firms may be unable to afford.

AI’s integration into architecture presents a unique opportunity to reflect on these challenges as we explore how the principles championed by Gaudí and Hadid can inspire future generations of architects.

The Main Entry Deadline for Architizer's 13th A+Awards is Friday December 6th! This season we're spotlighting the talent of architects who expertly balance global challenges with local needs. Start your entry.

Top image: Rooftop architecture by Antoni Gaudi at the famous La Pedrera (Casa Mila) in Barcelona, Spain via PickPik

Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre

Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre