Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

The 2023 Pritzker Prize has been announced and the winner’s reveal was met with mixed reactions. While some lauded the timeless elegance and simplicity of Chipperfield’s designs, others questioned why the institution would choose to elevate the “safe choice” and what values that conveys. For those in the latter camp, who met the announcement with a sigh, part of the constructive commentary was brainstorming architects who they’d like to see win.

While the Pritzker’s culture of naming a single figure rather than the teams of professionals who work to produce contemporary architecture remains questionable (the rules explicitly state that the prize must go to “a living architect or architects, but not to an architectural firm”), there are arguments for celebrating industry visionaries whose creative leadership guide the profession. Indeed, the prize is meant to “encourage and stimulate not only a greater public awareness of buildings but also inspire greater creativity within the architectural profession.” That said, the definition of architecture does not simply encompass buildings (scroll to see some landscape architects who have certainly “produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.”).

Architizer’s A+Awards program was founded with the precise aim of countering the culture of starchitecture, which erases the very foundation of architectural practice: collaboration. However, we also believe in thought leaders, and the following selections exemplify the spirit of what we celebrate: architecture that builds a better future.

Marina Tabassum

Left: Marina Tabassum Kaethe17, Marina-tabassum-pimo-2023 (cropped), CC BY-SA 4.0; Right: Bait Ur Rouf Mosque অজ্ঞাত, বায়তুর রউফ মসজিদ, CC BY-SA 4.0

Climate, materials, site, culture, and local history are hallmarks of Marina Tabassum’s output. Her Dhaka-based studio was founded in 2005, and the Bangladeshi architect’s most famous work, the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque epitomizes the approach that she takes across her diverse oeuvre. There, a symphony of light sings in a rhythm of unexpected beams and bursts against the exposed terracotta walls. It’s pure poetry. But then, there are her more practical designs like Khudi Bari, a modular mobile housing unit that is light weight and easy to assemble and specifically designed for climate victims in her native Bangladesh. Hers is an architecture rooted in the past and built for the future. We need celebrate this type of innovative and humanitarian approach to design over and above the monumental and symbolic.

Tatiana Bilbao

Left: Tatian Bilbao, Casa de América, Tatiana Bilbao, arquitecta mexicana, CC BY-SA 4.0; Right: MNXANL. Building originally designed by Tatiana Bilbao, 201805 The Exhibition Room at Jinhua Architecture Park, CC BY-SA 4.0

We live in a time of crises. While the term “Housing Crisis” is used universally, the plagues most countries in distinct and different iterations. Mexico City-based architect Tatiana Bilbao has a long history of engaging with this crisis as it manifests in her hometown. Since having worked as an adviser for the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing in Mexico City for two years early in her career, Bilbao has acted as a leader of architectural discussions and research into affordable housing — and not the anonymous cookie-cutter type that might come to mind. Beyond affordability, her designs consider how to build sustainable communities that are rooted in their locale. Tell me this doesn’t “demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision, and commitment,” that the Pritzker awards.

Kongjian Yu

Left: Carré et Rond (Yu Kongjian) – Parc du G” (CC BY 2.0) by westher; Right: GSAPPstudent, Kongjian Yu Lectures at Columbia GSAPP 2, CC BY-SA 4.0

While architectural enthusiasts outside of China may be less familiar with landscape architect Kongjian Yu, it’s time they started reading up. The founder of Turenscape has been on the forefront of adapting cities for a changing climate, and a longtime advocate of reversing assumptions about urban and regional development planning. Having coined the term “Sponge City,” his body of work is driven by an ecological approach to recovering the natural landscape of cities, and working with water rather than against it. While these projects may be rooted in ecology, the designer’s touch for adding a flare of tasteful manmade drama in a natural environment underlines the root belief of his studio; indeed, it is embedded in its name. The “Tu” refers to dirt, earth and land. Meanwhile, “Ren” denotes people, man and human beings. Together, “Turen” means earth man. This is the type of thinking all builders today must take.

Jeanne Gang

Left: The Aqua Tower and The St. Regis Chicago (Vista Tower) by Studio Gang, Chicago, IL Right: Columbia GSAPP, Jeanne Gang (22177033709), CC BY 2.0

The world’s tallest woman-designed building, St. Regis Chicago, was constructed by Jeanne Gang and her studio. When it was completed in 2020, the tower that it overtook to gain its title was none other the Aqua Tower, designed by the same architect. This simple fact speaks volumes about Jeanne Gang’s ambition, which is paired with seemingly limitless creative energy. Her contribution to 21st century skyscraper is undeniable, so it is fitting that she is based in Chicago, where the typology was first invented. Studio Gang’s portfolio is not limited to highrises, however. (Although, her team has masterminded plenty more innovative towers!) For example, their latest adaptive reuse project makes a hopeful statement about the future while their addition to the American Museom of Natural History is an signifiant contribution to museum typology.

MVRDV (Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs, and Nathalie de Vries)

Market Hall by MVRDV, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Since it was founded in 1993, this Rotterdam-based studio have been challenging public perceptions about what architecture can be and how it can evolve our definition of what a city is. Mixing typologies, upending formal expectations and urban relationships, and pushing the envelop of construction possibility, MVRDV does work that is anything but safe. Each project in their portfolio is delightfully unique, also challenging the traditional notion of an architect or firm developing an identifiable style. Instead, their projects are deeply rooted in an analysis of how buildings can activate (or re-activate) the urban fabric and the public, resulting in architecture that is place-specific, even if not rooted in tradition (subverting a common preconceived notion about contextual design). They also model how urban density does not need to come at the cost of traditional community bonds.

James Corner

Left: Photo by Jake Chessum Right: High Line by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, New York, NY

As a path breaking landscape architect who has already been the first of his ilk to receive a handful of awards traditionally reserved for building designers, James Corner is well positioned to be the first landscape designer to win a Pritzker. His New York-based firm, which takes his name, crafts urban environments that are more than just green spaces; in addition to ecological benefits, his designs are undergirded by a deep concern with the social and the economic. Corner was at the forefront of thinking about post-industrial landscapes, and designs such as his famous High Line (in collaboration with Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Piet Oudolf) positioned him as a leader in the field, and redefined how the broader public view landscape architects and architecture. Since then, his firm has continued to push the bounds of public and industry understanding about urban public space and ecological remediation, reimagining aging infrastructure as “places to enchant.”

Frida Escobedo

Left: https://www.flickr.com/people/gsapponline/, Frida Escobedo, CC BY 2.0; Right: Images George Rex from London, England, Serpentine Pavilion 2018 VIII (42185361435), CC BY-SA 2.0

Having skyrocketed to global fame in 2018 when she was named the youngest architect ever invited to design the Serpentine Pavilion (and only the second woman to do so), it should come as no surprise that Frida Escobedo is on this list. However, this is not why she deserves to be given the Pritzker. When she was named to takeover the MET wing design from this year’s laureate, the museum director Max Hollein put it best, saying “In her practice, she wields architecture as a way to create powerful spatial and communal experiences, and she has shown dexterity and sensitivity in her elegant use of material while bringing sincere attention to today’s socioeconomic and ecological issues.” Beyond the museum addition, her portfolio ranges from hospitality and hotel restoration to interior commercial projects to residential design — all commissions that are the bread and butter of most architects, making up the fabric of the everyday, as opposed to the big-ticket cultural projects typical of starchitects.

Toshiko Mori

Left: Photo by Ralph Gibson Right: House in Connecticut II, Toshiko Mori Architect, New Canaan, CT Photo by Paul Warchol Photography

The Japanese-born and New York-based architect Toshiko Mori made a name for herself by her poetic takes on modern architectural style, deely rooted in research that produced material innovation and common-sense sustainability. Through her eponymous firm over the past four decades, she has constructed beloved buildings around the world and built a career as an industry leader through her dedication to pedagoy. While the Pritzker recognizes built output, and not thought leadership, from becoming the first female professor given tenure at Harvard to her investigations into sustainability in design on World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on the Future of Cities to her advocacy for community engagement through Architecture For Humanity, her positive impact on the profession shouldn’t be taken lightly. These research interests are also visible in her built output, including THREAD: Artists’ Residency and Cultural Center where Mori used parametric design to expand the structural possibilities of the vernacular African home.

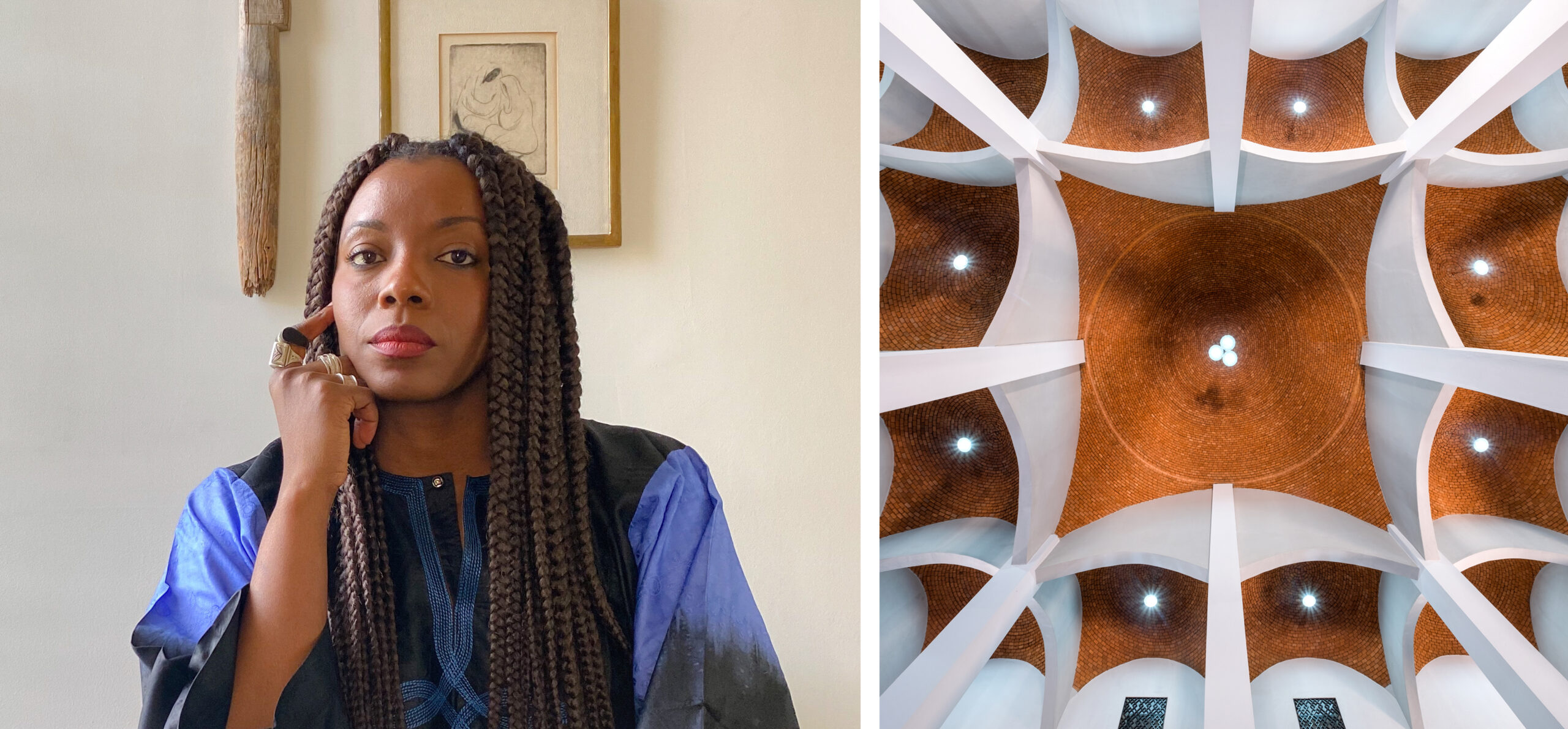

Mariam Issoufou Kamara

Left image: Mariam Kamara, Mariam Kamara OTRS, CC BY-SA 4.0; Right image: HIKMA – A Religious and Secular Complex by Mariam Issoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī) + Yasaman Esmaili, Dandaji, Niger Photo by James Wang

If Mariam Issoufou Kamara were to win the Pritzker next year, she wouldn’t be the youngest laureate in the prize’s history (that bar was set by Ryue Nishizawa was aged 44 in 2010), although she’d be damn close. The founder and principal of Mariam Issoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī) , in Niamey Niger and the Seattle-based collective united4design, is known for harnessing low-cost, local materials, including raw earth and recycled metal. One example of this is her Hikma Community Complex, a building that has been lauded for its sustainability specs and that draws on local construction techniques and evolves them. Bringing three programs—a mosque, a library and a community center—under one roof, the Kamara’s design bringing “secular knowledge and faith” together “without contradiction.” Perhaps she needs time to build out her portfolio before the Pritzker comes her way, it would be thrilling to cast the spotlight on someone “designing culturally, historically and climatically relevant solutions to spatial problems inherent to the developing world.”

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.