Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

On December 7th, 2021, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) announced its transition to employee ownership through an Employee Benefit Trust (EBT). In a press release, which led with a quote from the late Dame, “I think there should be no end to experimentation,” the firm contextualized the decision as a bid to build a more democratic profession — one that will be more accessible and egalitarian, where each employee will have a voice.

For some, the move represented the culmination of a growing trend where, over the past decade, more and more firms have switched to employee ownership schemes. The reorganization also points to a more significant industry shift from hierarchical management towards more democratic models. Indeed, ZHA is undoubtedly not the first firm to do so, although it is the most high profile to date. Spanning offices in China and the UK, the 42-year-old practice now employs more than 500 staff.

So, could its decision represent a seismic shift that will create not just ripples but waves in the profession?

Heydar Aliyev Center by Zaha Hadid Architects, Baku, Azerbaijan | Popular Choice, 2014 A+Awards, Theatres & Performing Arts Centers

While most firms are owned by individuals, employee ownership schemes are based around a trust. In this model, stock is distributed amongst employees based on criteria such as tenure or pay, amongst other things. Whether it is an EBT (in the UK) or an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) in the USA, there are various options within stock-sharing models for building a bridge between a firm’s profits and its employees. For example, a company may choose between the direct, indirect, or hybrid models, each with different ways of structuring their boards’ relationships to the employees. The idea is that employees are incentivized by owning shares in the business and will be motivated by its financial success; there are also the personal benefits that come with insurance and income tax breaks.

Moreover, as boomers (the owners of most large firms) begin to reach retirement age or the end of their careers, the decision to switch to employee ownership models is often bound to succession planning and the need to prepare for leadership transitions. It creates space for younger staff to rise in the ranks, who, saddled with unprecedented levels of student debt, would otherwise be unable to afford to do so. However, the implications, are larger than this — and, as the industry adjusts to the cultural and economic realities of more recent graduates, ZHA may well be on the forefront of a generational shift.

Most millennials have come to accept that unlike their parents, who held one or just several jobs throughout their lifetimes, they would likely work in many different companies before retirement. Some have even called them the “job-hopping generation.” However, the model put forth by EBTs and ESOPs often leads to greater staff retention and job security, also creating new possibilities for intergenerational wealth transfer. For the standpoint of a firm, this makes it easier to built on experience. Could the rise of such models change the course of the labor market?

Again, while lots of firms have been experimenting with these types of models, given their reputation and standing, ZHA’s preeminence in the industry pushes the concept into the spotlight as it has never been before. What makes the decision even more remarkable is the fact that the firm’s identity has been so profoundly tied to its principals throughout the years — first with Dame Zaha and now, to a lesser extent, Patrik Schumacher.

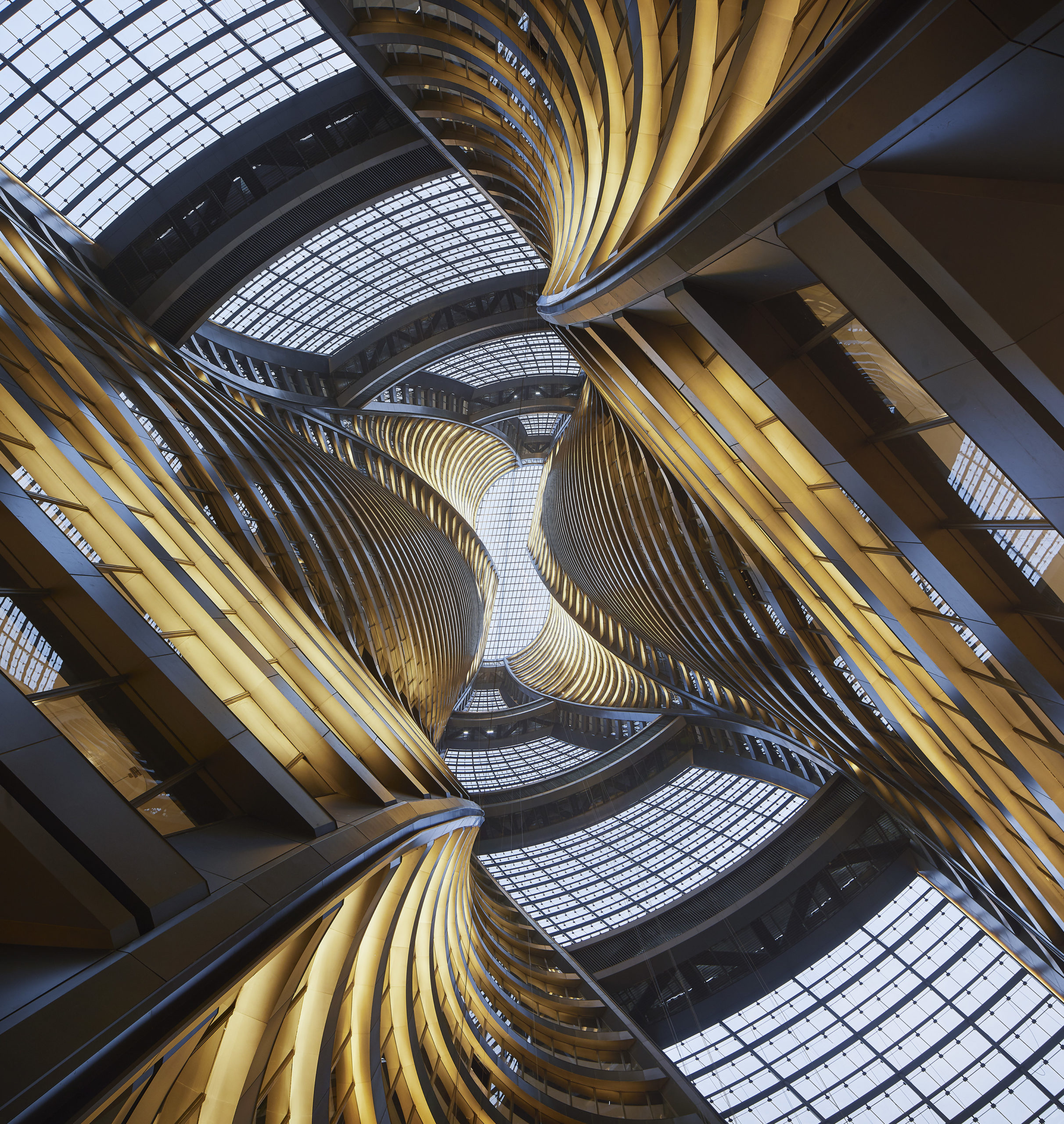

Leeza SOHO by Zaha Hadid Architects, Beijing, China | Jury Winner & Popular Choice, 2020 A+Awards, Office – High Rise (16+ Floors)

While EBTs and ESOPs may be a natural fit for the more horizontal diffusion of power in many architecture offices, the business model also runs contrary to the historical concept of the “genius architect”, as well as the more recent phenomena of the rise of the “starchitect”. Instead, it reinforces the collective and collaborative working methods that have long been the fuel that has sustained such offices but are only now being recognized as the true key to any firm’s success.

On the one hand, it seems that architectural practices are particularly well-suited for these types of flat, or lateral, hierarchies. Indeed, architecture and engineering firms already dominate lists of employee-owned companies in the US. On the other, recent and long overdue reckonings with racial and gender discrimination have often dovetailed with critiques of power structures in corporate hierarchies, including architectural practices. ZHA’s decision is momentous precisely because it comes on the heels of the “toxic dispute” that arose in the wake of Dame Hadid’s untimely death and revealed such problems within the firm.

Throughout the legal battle between long-term collaborator and practice principal Schumacher and the celebrated Iraqi-born architect’s estate, one prominent point of contention was the structure of the EBT to which all shares in the architecture practice were to be transferred. Schumacher, the trust’s chair, sought personal powers of veto over the company’s board of trustees. Meanwhile, the court case unveiled independent legal investigations from 2019 alleging “numerous failings of corporate governance” within the firm, and the judge ultimately ruled on the side of the estate.

Given this turbulent history, it is particularly pertinent that their December 7th, 2021 press release lists “independent organizational systems and structures” as a benefit of employee ownership that will “give every member of [their] team a voice in shaping the future.”

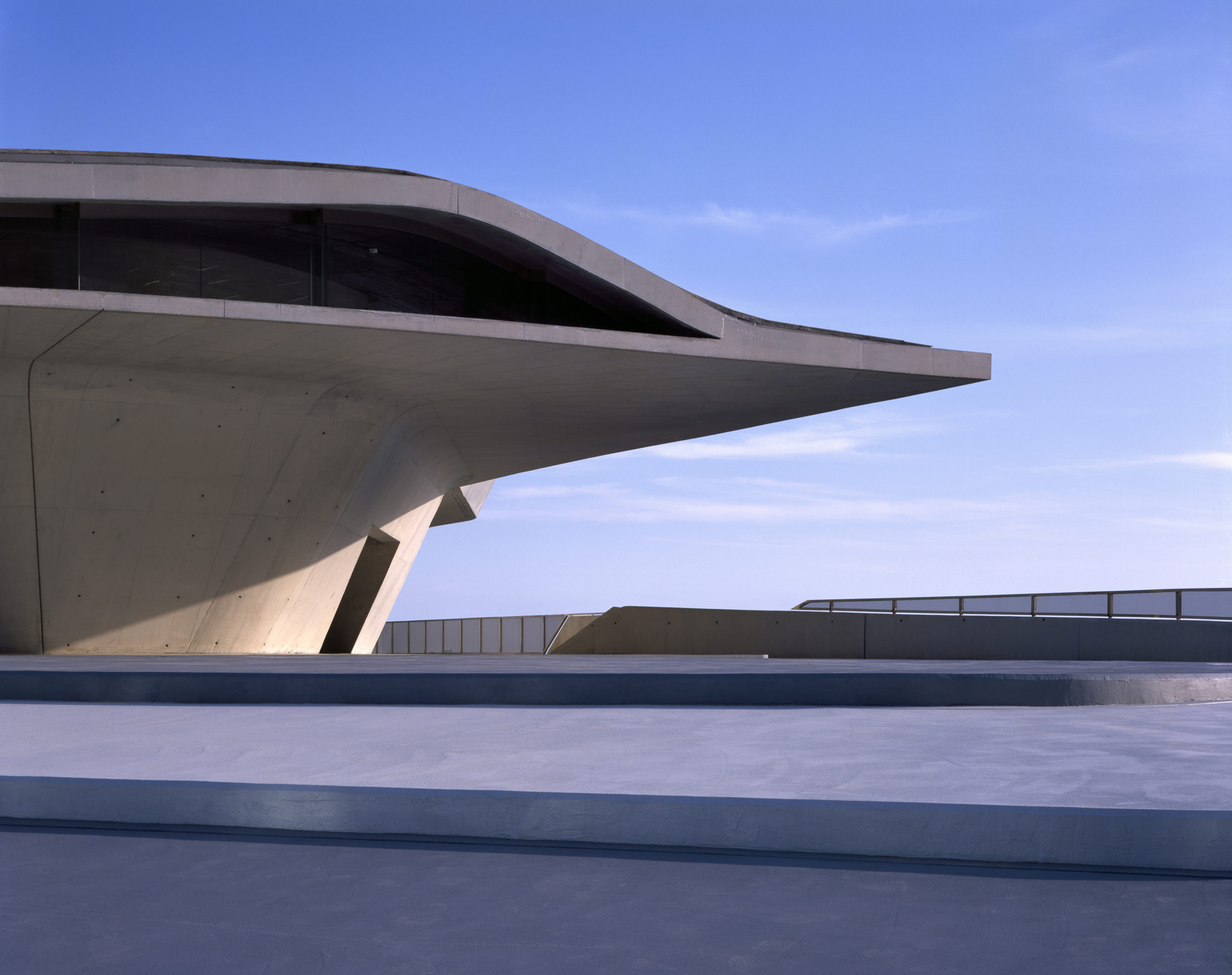

Salerno Maritime Terminal by Zaha Hadid Architects, Salerno, Italy | Jury Winner, 2017 A+Awards, Transportation Infrastructure

Indeed, beyond the financial advantages, there are a host of positive cultural outcomes that could uproot some of the longstanding issues in the industry, especially those that have become attenuated in recent years. Employee ownership models require more transparency in the organization: whether by sharing the books, being more open about the business’ performance or by sharing career progression decisions are made. This is what is meant by ‘horizontal’ or ‘lateral’ power structures.

These forms of openness can motivate employees and create a healthier environment where juniors in the office — particularly women — are less likely to be confronted with unhealthy power imbalances with their superiors. Moreover, recent studies of workplace culture in employee-owned companies have shown the benefits for racial and gender wealth equity.

A recent study by the Rutgers Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing, funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, demonstrates that such models employee share ownership shrinks (although, notably, does not entirely close) gender and racial pay gaps. The main emphasis of this study is on equitable asset building. Barriers to entry for minorities still exist in such models; more research is required to assess the impact of that higher rates of job retention and mentorship could have on professional advancement.

Within this context, ZHA’s decision to restructure for employee ownership should be seen as a crossroads for the architectural profession. Coming on the tail of power abuse allegations in their firm, ZHA’s announcement also sends a message about how architectural practices can take concrete actions towards becoming more equitable.

Meanwhile, as a prominent firm that is so tightly bound to its founder’s name and ethos, this transition sends a message that employee ownership is possible for any firm — even those who rely on their founder for branding. It champions a model of design practice that values (both financially and symbolically) collaboration, which anyone familiar with the industry should know is the backbone of any piece of truly great architecture. If there were any questions about when the curtain would finally close on the era of the starchitect, perhaps this may be its final death knell.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.