The jury and the public have had their say — feast your eyes on the winners of Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive future program updates.

Energy facilities have traditionally been situated on the outskirts of cities and towns, much like kitchens were conventionally tucked away in the corners of homes, separated from living spaces. This historical approach reflects a mindset that viewed these essential services as purely utilitarian spaces rather than integral parts of daily life and social interaction. Similarly, energy facilities were generally placed far from city centers to minimize their visual and environmental impact.

However, just as modern architectural trends have brought kitchens into the heart of homes — transforming them into vibrant, central hubs of activity and social interaction — contemporary urban design is rethinking the role of energy facilities. Today, there is a growing recognition that these vital infrastructures can be more than mere background utilities. Like kitchens becoming focal points that enhance functionality and aesthetic appeal of living areas, integrating energy facilities into city centers reflects a progressive approach that values sustainability and innovation.

Urban Energy Districts: A Sustainable Shift from Traditional Power Plants

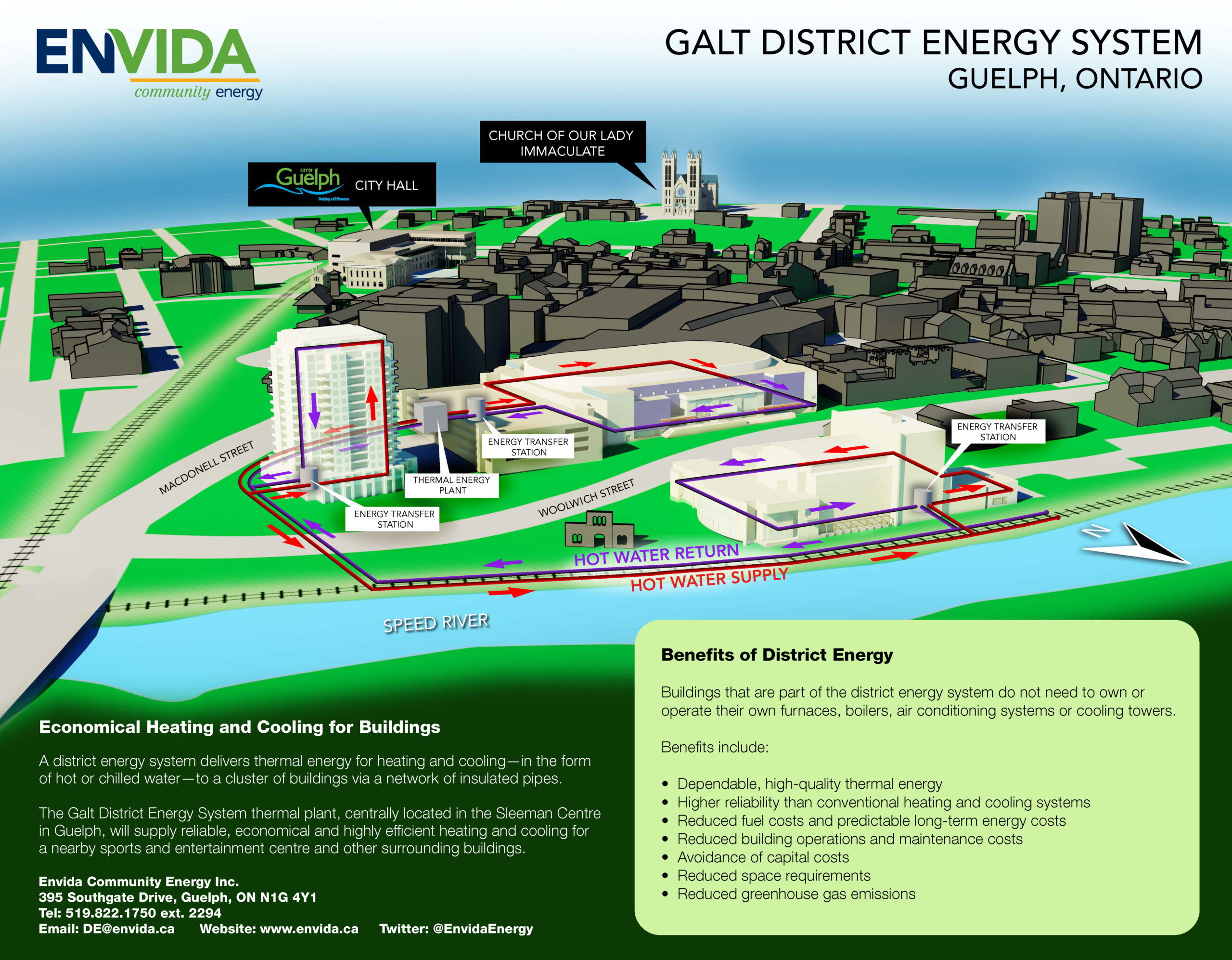

Illustration showing how the district energy system at Sleeman Centre in downtown Guelph can expand to provide heating, cooling, and hot water to other buildings in the area. | Illustration courtesy of the City of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, via Flickr.

Integrating energy districts into urban settings carries significant implications, especially regarding environmental and safety concerns. Traditionally, power plants were located outside city boundaries to mitigate risks such as emissions, noise and potentially catastrophic failures. This peripheral placement was necessary to protect urban populations and accommodate the extensive infrastructure — such as cooling ponds — required by these facilities.

Safety and environmental awareness, particularly the goal of decarbonization by 2050, are driving cities worldwide to shift from traditional power plants to energy districts. This transition supports a more sustainable and efficient energy supply, reducing carbon emissions and enhancing urban resilience.

Unlike power plants, which are large, centralized facilities designed to generate electricity on a large scale and serve extensive regions, energy districts are typically local and decentralized, serving specific areas such as neighborhoods, university campuses or commercial complexes. They integrate cohesively into the local urban fabric, providing multi-functional energy services including heating, cooling and electricity generation, which optimizes the use of local resources and infrastructure. These systems often incorporate renewable energy sources like solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal, as well as technologies such as combined heat and power (CHP) and heat recovery systems.

In contrast, power plants rely on fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas and oil, although there are also nuclear and some renewable power plants like hydro, solar, and wind. The focus is on maximizing efficiency through local generation and distribution, reducing transmission losses, and using waste heat for additional energy needs.

Harnessing the Power of Urban Energy: Exemplary Districts Leading the Way

The Energy Tower in Roskilde, Denmark. Designed by Dutch architect Erich van Egeraat. | Photo by kboul via Flickr.

Energy districts serve communities with essential heating, cooling and electricity services. They can be found in urban settings, including universities, hospitals, airports and densely populated areas.

Notable examples of energy districts worldwide include Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, renowned for its sustainable urban development and extensive use of renewable energy sources. Toronto’s Enwave Deep Lake Water Cooling system demonstrates innovative district cooling using lake water as a heat sink. Cornell University’s Combined Heat and Power Plant in Ithaca, New York, provides efficient energy solutions tailored to campus needs. Worth mentioning is the Energy Tower in Roskilde, Denmark, a combined heat and power (CHP) plant that serves as a critical energy infrastructure for the city of Roskilde and its surroundings. The plant’s architecture also reflects its function, with a distinctive tower structure that houses the biomass boilers and other essential equipment for energy generation and distribution.

These energy districts demonstrate how cities can implement sustainable energy solutions, reducing environmental impact and enhancing resilience. From an architectural and urban planning perspective, they show how infrastructure can be integrated into urban landscapes, combining functionality with aesthetic appeal. These systems provide a blueprint for the future of urban energy infrastructure, highlighting innovative design and sustainable practices.

Harvard’s DEF: Combining Functionality and Aesthetic Appeal

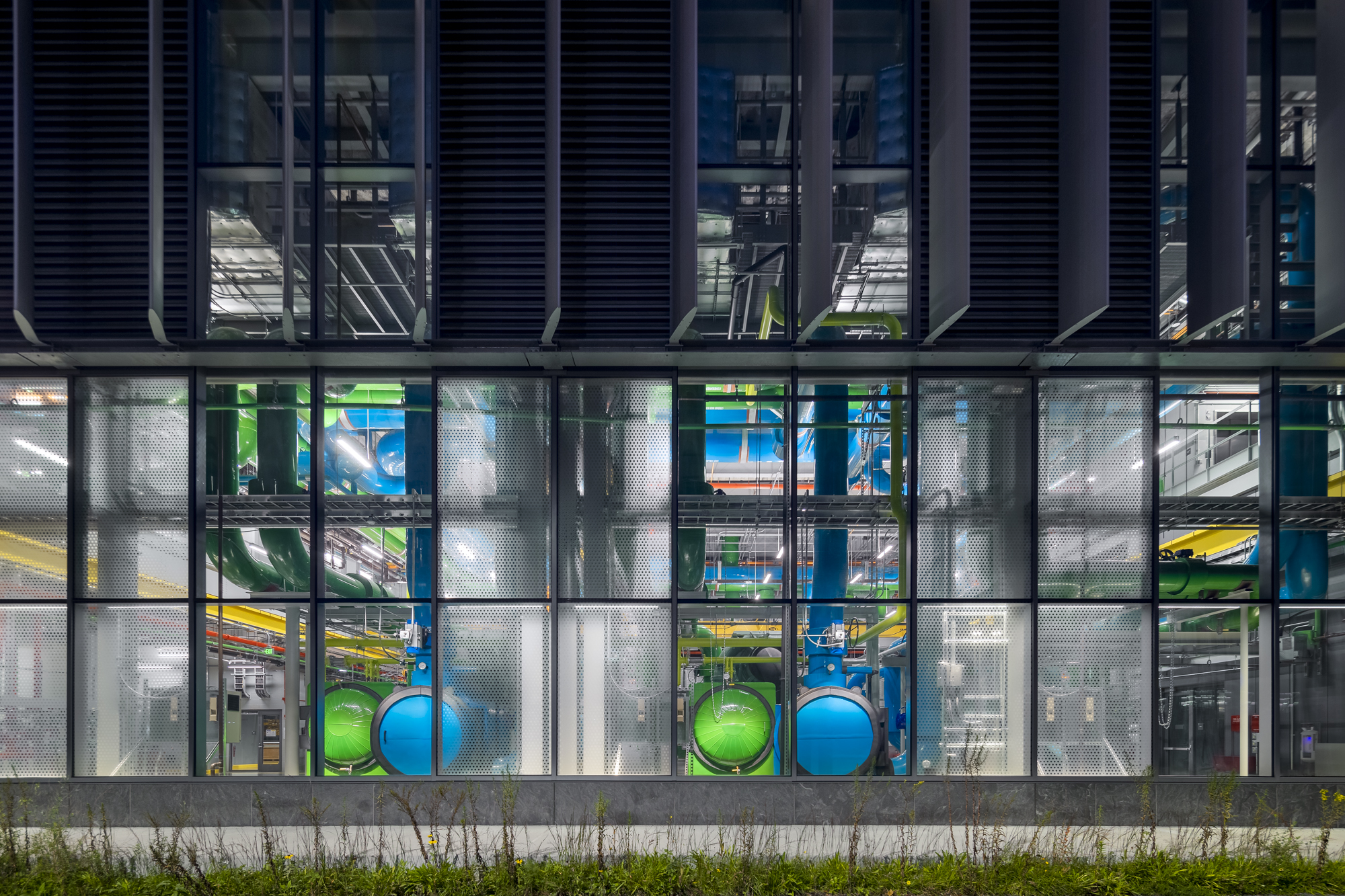

Harvard University District Energy Facility by Leers Weinzapfel Associates, Boston, Massachusetts, United States. | Photo by Brad Feinknopf | Jury Winner, 12th Annual A+Awards, Factories & Warehouses

Harvard University District Energy Facility by Leers Weinzapfel Associates. Boston, Massachusetts | Jury Winner, 12th Annual A+Awards, Factories & Warehouses

The 55,000 square foot District Energy Facility (DEF) at Harvard University’s Allston campus is a compelling example of integrating an energy district into an urban environment. Located within the Allston campus, it demonstrates how such facilities can blend with the scale of their surroundings while showcasing architectural excellence. Not only does the DEF meet functional needs, but it also enhances the campus landscape with its modern design and sustainable features.

Located in a formerly deserted rail yard, the DEF is to be surrounded by science and engineering buildings, a conference hotel and mid-rise residences. Its cubic form with rounded corners ensures flexibility for future development while maintaining a bold and refined presence. Petal-like anodized aluminum fins wrap around the building, revealing or concealing equipment areas. This design visually celebrates the numerous benefits of district energy plants: resiliency, energy efficiency, reduced energy costs, decreased carbon emissions, lowered air pollution and minimized noise.

The DEF, the first building on Harvard’s Allston campus, began supplying utilities to the Science and Engineering Center in 2019. Positioned at a pivotal site south of Western Avenue, the DEF is a prominent, permanent support facility that complements the evolving campus landscape, including future academic and research buildings.

The construction of the DEF offers an opportunity to enhance urban and campus infrastructure design. Once hidden in the “backyard” of campuses — like kitchens tucked away in the corners of homes — today’s infrastructure plants are centrally located to serve multiple buildings and relate to nearby structures in scale; an innovative approach that celebrates their energy and robust beauty, making them good neighbors.

The facility comprises mechanical and electrical spaces that contain energy production, conversion, and distribution equipment. Designed for resiliency, flexibility, and innovation, the DEF aims to transition to a fossil-fuel-free future, withstand climate impacts such as storm surge flooding, and provide reliable heating, cooling, and electricity on campus.

Urban Innovation: How Energy Districts are Transforming Cityscapes

Larkin Street Substation Expansion by TEF Design, San Francisco, California | Photo by Mikiko Kikuyama.

The European Climate Change agenda aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, presenting a significant challenge for the energy sector. Positive Energy Districts (PEDs) are becoming increasingly important as urban innovation labs and promising strategies for living in a climate-neutral way. They are designed to speed up decarbonization processes and advance the ecological transition.

In this context, energy districts are designed to blend with their surroundings, contributing to urban environments in both functional and aesthetic ways. Unlike traditional power plants on the outskirts, these facilities are integrated into cityscapes, symbolizing a commitment to transparency, efficiency, and environmental stewardship. Energy districts are designed not to replace conventional power plants but to complement and enhance the overall energy landscape by providing localized, efficient, and sustainable solutions.

This approach allows cities to showcase their dedication to sustainability and resilience, akin to a home with an open kitchen layout that fosters a welcoming and connected atmosphere. This evolution represents a significant step towards creating urban spaces that are not only functional but also beautiful, sustainable and integral to the daily lives of their inhabitants.

The jury and the public have had their say — feast your eyes on the winners of Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive future program updates.