Architects, interior designers, rendering artists, landscape architects, engineers, photographers and real estate developers are invited to submit their firm for the inaugural A+Firm Awards, celebrating the talented teams behind the world’s best architecture. Register today.

Great design brings environment and culture together. For Bangkok-based design firm LANDPROCESS, their work is helping to shift cities to a carbon neutral future by confronting climate futures. Founded in 2011 by landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom, the firm was recently given a 2020 A+Awards Special Honoree Award for the Thammasat University Urban Rooftop Farm project. Prioritizing global food security, health and the environment, the team utilized neglected spaces to efficiently and sustainably produce food.

The team at LANDPROCESS created the Urban Rooftop farm to re-purpose 236,806 square feet of unused rooftop space at Thammasat University. The result is Asia’s largest organic rooftop farm. Architizer spoke with firm founder Kotchakorn Voraakhom about the project’s urban impact and how it feels to have been named a Special Honoree this year.

Eric Baldwin: LANDPROCESS was founded with the goal to shift cities to a carbon neutral future and confront future climate uncertainty. For Thammasat University’s Urban Rooftop Farm, how did you utilize neglected spaces to address these ideas?

Kotchakorn Voraakhom: LANDPROCESS was created upon the idea that landscape architecture can provide solutions to tackle climate uncertainty and find the right balance between urban ecological health and development. In overcrowded capitals like Bangkok, where open space is now almost impossible to find, urban developers across space-starved cities are seeking new room to build on. Neglected spaces, especially countless of unused concrete rooftops, pose new possibilities. Instead of adding new or leaving vacant environmentally-degrading concrete surfaces, we can transform those wasted spaces into environmentally-beneficial and much-needed public green space.

Fixing social and environmental issues through architecture is a must. Forgotten rooftop spaces can actually present numerous opportunities to promote a healthy, equitable, inclusive city for all. It may sound idealistic, but we the designers, Thammasat University and surrounding communities have actually achieved this by creating the largest urban farm rooftop in Asia.

What were a few of the major goals for the Urban Rooftop Farm, and how were these realized?

What were a few of the major goals for the Urban Rooftop Farm, and how were these realized?

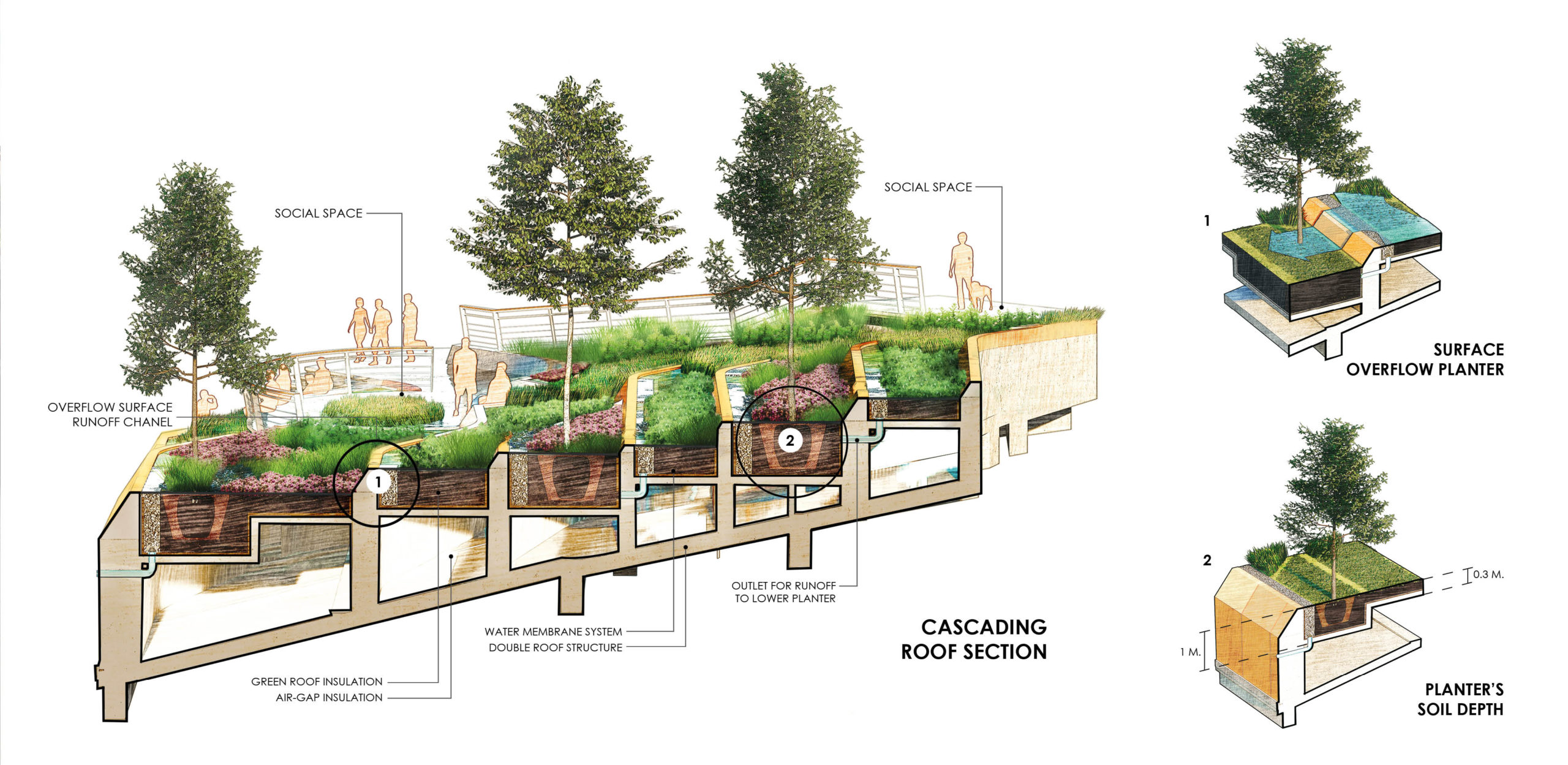

Slowing excessive runoff, relieving flash floods in flood-prone cities, turning the urban heat island effect into infinite clean energy, creating not just visual greening but also productive green space, as well as addressing toxic agrochemicals — Thailand is one of the top five importers of chemical pesticides — these were the questions I had in mind, for whether the urban development that caused these problems can fix them too.

Through a single architecture, the Thammasat Urban Rooftop Farm fixes one root problem which multiplies its effects. As landscape architects, I feel that we are all obligated to put a focus on the sustainable urbanization movement in our work in order to build livable cities of the future.

I’d like to give kudos to our wonderful client, Thammasat University, for holding a vision and mission in sustainable development. As an educational institution, it’s a perfect example to lead the initiative for our city while demonstrating to the younger generation how to engage in a healthy lifestyle as well as how to contribute to a circular campus economy.

I’d like to give kudos to our wonderful client, Thammasat University, for holding a vision and mission in sustainable development. As an educational institution, it’s a perfect example to lead the initiative for our city while demonstrating to the younger generation how to engage in a healthy lifestyle as well as how to contribute to a circular campus economy.

The art of this architecture not only lies in its complex construction, but also in the work of negotiation, given the various stakeholders involved. This architectural piece was made possible through the cooperation of all landscape architects, architects, engineers and decision-makers.

Your design took the form of a cascading rooftop inspired by traditional rice terraces. How can designers learn from existing techniques and local traditions to address issues of energy, waste and public space?

Your design took the form of a cascading rooftop inspired by traditional rice terraces. How can designers learn from existing techniques and local traditions to address issues of energy, waste and public space?

Traditional agriculture is the perfect integration of human design with nature, an art-form deeply rooted in our culture. With the technology we have today, we can interpret what we’ve learned from the past to come up with future resilient design. For many developing countries, imported design and technology means expensive and high maintenance solutions because we’ve adapted to mimicking it without understanding the cultural maintenance and setting, thus making seemingly good architecture irrelevant to its context.

By looking at what has proven throughout time to be practical in the vernacular and local context, with technology we have today, we can progress by making architecture unique and native to its motherland and speak its own mother tongue. Because the purpose of architecture is not only to serve the client’s needs and create impressive forms, but also fix its city’s issues, each has our own ability to confront the future climate uncertainties that we are all experiencing differently throughout the world.

Many of the A+Award winning projects from this year contain elements that address some of today’s most pressing issues, from climate change to rapid urbanization. What does winning this Special Honoree mean to the practice and your work?

Many of the A+Award winning projects from this year contain elements that address some of today’s most pressing issues, from climate change to rapid urbanization. What does winning this Special Honoree mean to the practice and your work?

Firstly, thanks to the creators of the A+Awards for addressing the future of architecture and linking it to the pressing issue of climate change. I feel a special obligation for our profession to address these challenges, since our works is an important part of urbanization, the root cause of many of our environmental issues today. Winning the Special Honoree is a big step towards demonstrating our need to drive future architecture works to not only define aesthetics and human design philosophy, but also environmental balance.

Architecture should not only be a consumer role, but also give back to its surroundings. In my practice as a landscape architect, being awarded in the architecture realm really aligns with our belief that landscape architecture can transform buildings into climate solutions.

Furthermore, the Thammasat Urban Rooftop Farm shows that inclusive design actually goes beyond just humans, but also includes insects, birds, water, air and various other natural elements we often forget to consider as part of us. After all, the architecture we build today isn’t just for our generation, but also for the next ones — and they don’t seem to be very happy about the city and environment that we’re leaving them.

Where I come from, ‘grand’ pieces of architecture will mean nothing if our entire city will flood and sink in the near future. Today, there are many urban development projects which are completely irrelevant once put under the lens of climate change. We are currently at the point of ‘adapt or die’, and adaptive solutions should not come from business-as-usual thinking.

Where I come from, ‘grand’ pieces of architecture will mean nothing if our entire city will flood and sink in the near future. Today, there are many urban development projects which are completely irrelevant once put under the lens of climate change. We are currently at the point of ‘adapt or die’, and adaptive solutions should not come from business-as-usual thinking.

Nature is changing, the climate is changing, and so we, too, need to change and understand that fixed definitions of nature from one stage will no longer apply in this climate of uncertainty we are currently confronting. I don’t mean to say my team’s work is already addressing all the issues mentioned, but I do believe in learning, and am very excited about the solutions we can provide for the challenges that we’ll face.

Looking to the future, how do you think landscape architects and designers can embrace climate challenges to address local urban issues?

In my country, landscape architecture practices are often perceived in the shadow of architecture. Truth is, we are not simply designers of visual greening aesthetics, but we are also the re-creators and fixers of urban ecology. With current environmental degradation, we can see ourselves immersed in that scope of work — it’s a must that both landscape architects and architects come together to combine our approaches to figure out climate solutions.

My profession, landscape architecture, should not be left as the last amenity to finishing up a project or using the last of the budget for some minor greening. I’d like to see landscape architecture be considered as the source of initial concept, as the voice and restorer of a healthy urban environment. If architects and engineers collaboratively work more with landscape architects, I’m certain we can strengthen our climate-focused architecture in very significant ways.

My profession, landscape architecture, should not be left as the last amenity to finishing up a project or using the last of the budget for some minor greening. I’d like to see landscape architecture be considered as the source of initial concept, as the voice and restorer of a healthy urban environment. If architects and engineers collaboratively work more with landscape architects, I’m certain we can strengthen our climate-focused architecture in very significant ways.

To start a project, we need to put everyone on board at par to openly discuss and brainstorm, especially across various disciplines, without fear of judgement or domination. With that, I’d like to express my gratitude and officially thank the Arsom Silp Institute, the architect and engineer organization whom we worked with on this project, for allowing us to be a major part of the overall concept.

It was an honor to be able to freely share and discuss, making for such beautiful collaboration to create this integration between landscape architecture and architecture in the Thammasat Urban Rooftop Farm.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter