Feast your eyes on the world's most outstanding architectural photographs, videos, visualizations, drawing and models: Introducing the winners of Architizer's inaugural Vision Awards. Sign up to receive future program updates >

In the February of 1909, the front page of the Parisian newspaper, Le Figaro, was emblazoned with a bold headline: “The Manifesto of Futurism.” Penned by Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the text was a revolutionary rallying cry. Marinetti vehemently denounced the ways of the past, pledging to free the Italian people from its constrictive heritage. He was determined to embolden a new aesthetic language based on industry, war and the machine age.

Marinetti’s avant-garde and extreme vision for the future quickly took hold in his homeland. Painters, sculptors, poets, musicians and architects all adopted his ideologies and translated them into their work; a movement had begun. Marinetti lead The Futurists to outline a new world, depicting stylized urban landscapes and new technologies, including trains, cars and airplanes. All of these representations glorified speed and violence, while elevating the working classes. The Futurist Movement aimed to catalyze change by expressing and embracing modern life’s dynamic energy and movement, forcibly injecting it into every aspect of society.

The Futurists, Marinetti Sant’Elia Sironi and Boccioni, 1916

The Futurists, as a collective, celebrated the idea of a modern city. By rejecting historicism, they sought to revolutionize urban life. While many in the movement were painters, authors or poets, Mario Chiattone and Antonio Sant’Elia were the key architects positioned to realize their alternative vision of the future. The former had a thorough grounding in modern art from a young age. His father, Gabrielle Chiattone, was an accomplished artist himself. He was also a wealthy connoisseur of contemporary art and became one of the earliest patrons of The Futurist’s works.

The latter, on the other hand, was, and is still, regarded as a highly influential Italian architect, born in Como, Lombardy. Sant’Elia was a builder by training before becoming a draughtsman and his involvement with the Futurist movement. After studying together, Chiattone and Sant’Elia shared a studio where they worked together on their vision for the future.

Industrial Building with Corner Tower, 1913

While Chiattone never truly defined himself as a Futurist, Sant’Elia embraced the Futurist Manifesto whole-heartedly and subsequently outlined his own goals for the movement in text that was edited by Marinetti and issued as “Futurist Architecture: Manifesto.” This body of work glorified the beauty of technology, iron and transportation while altogether rejecting neo-classicism. It was bold and visionary, and subsequently cemented him as a significant contributor to the Futurist Movement despite his untimely death at 28 years old.

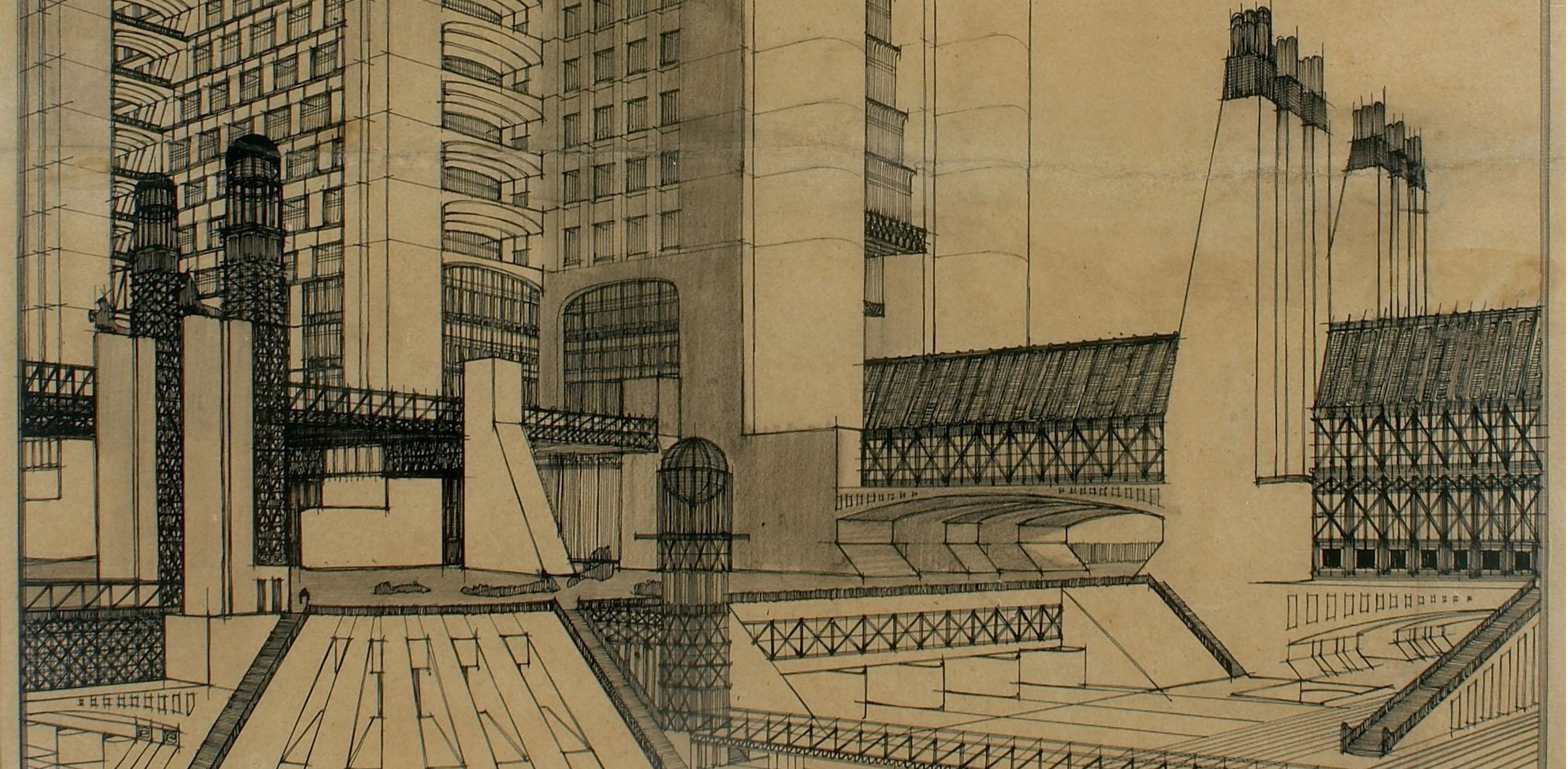

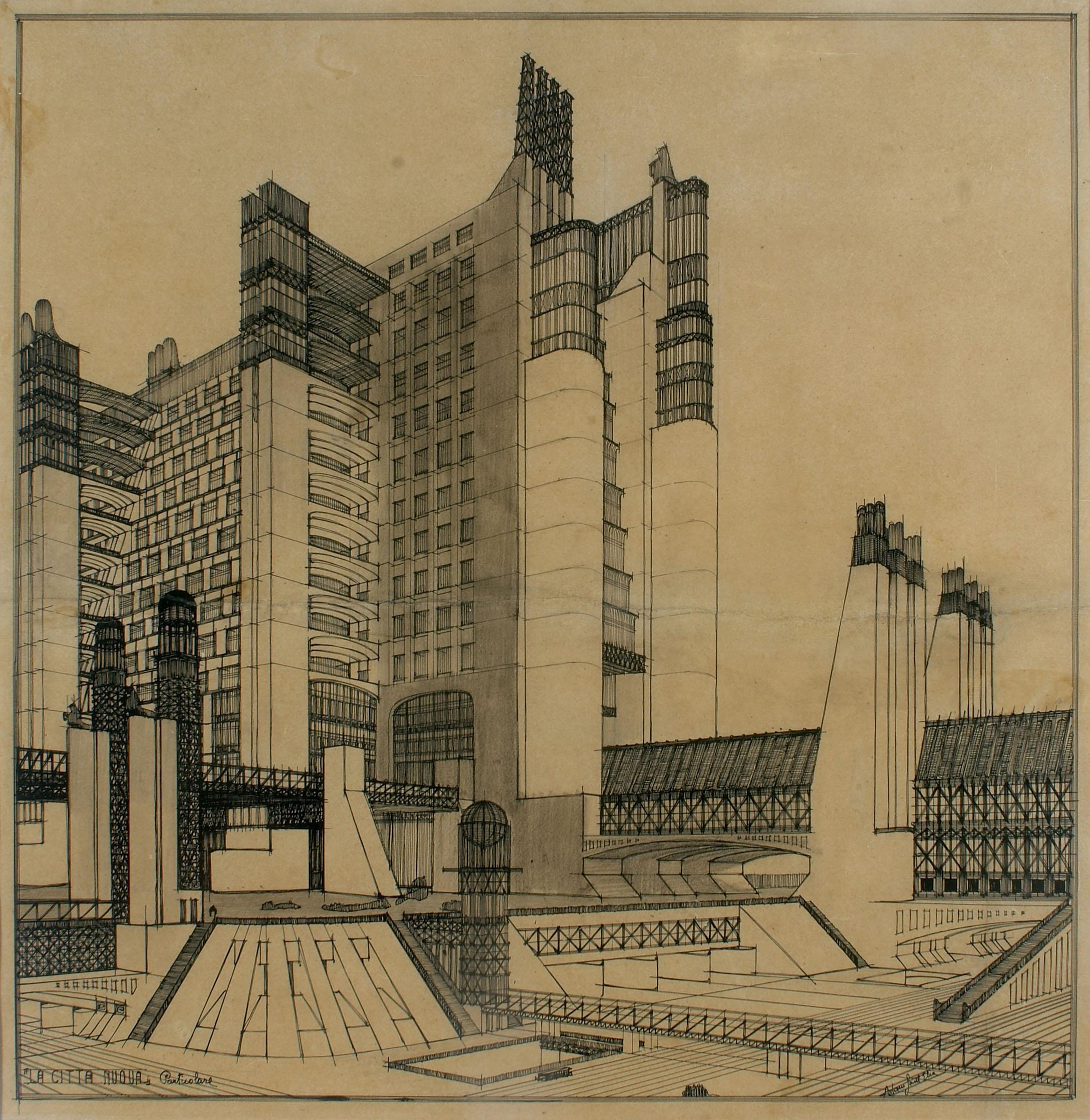

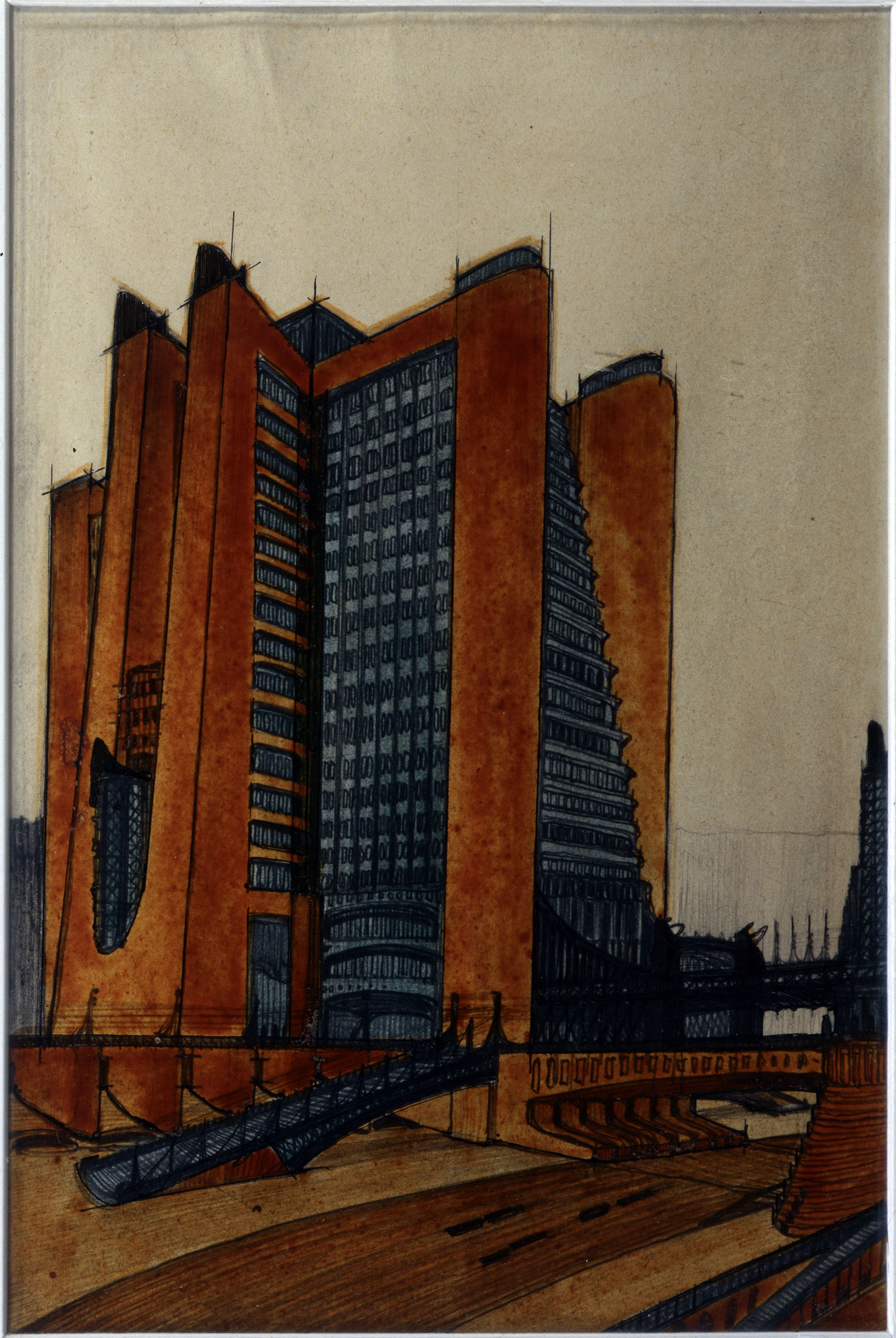

The New City, 1914

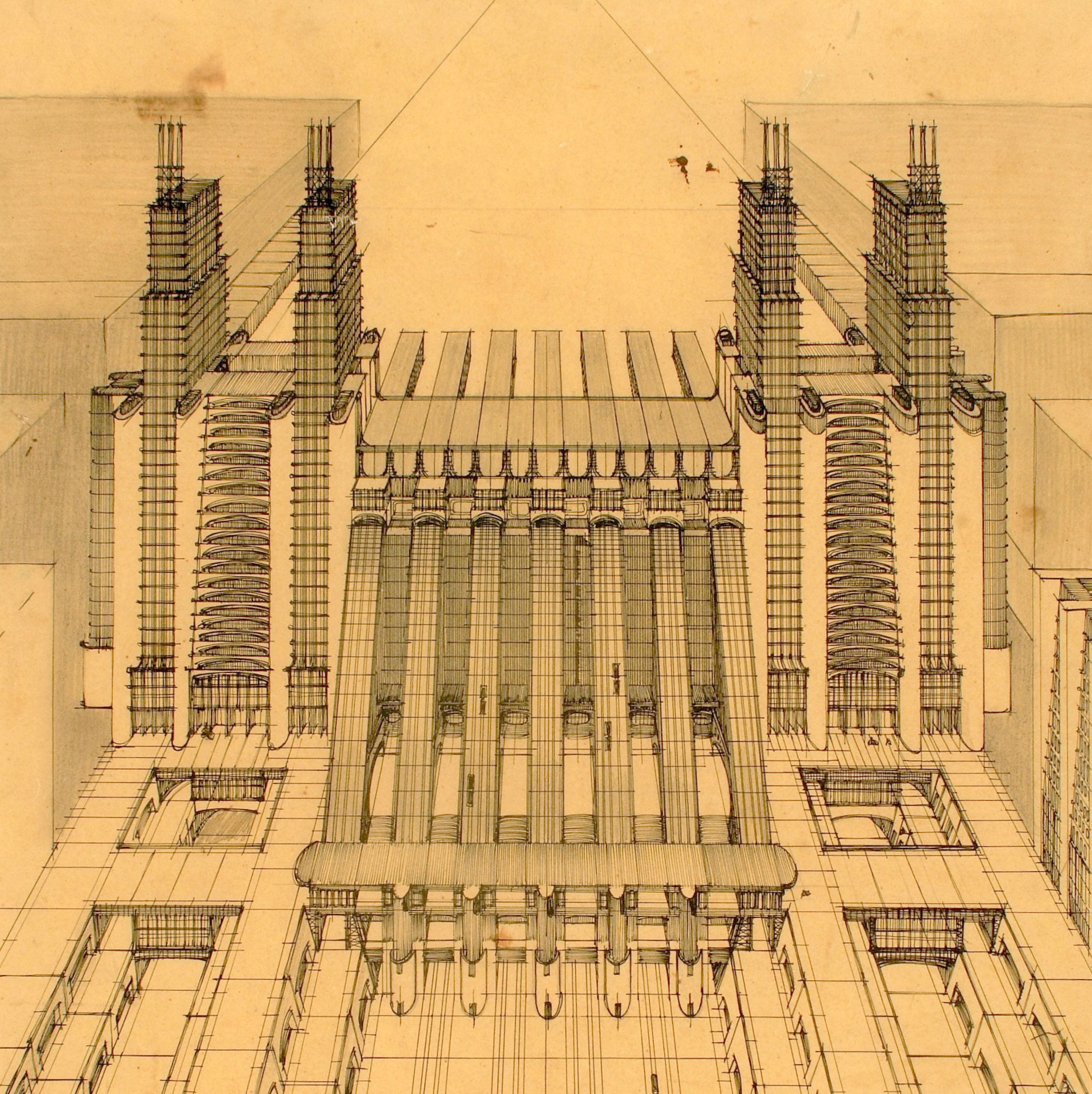

Air and Train Station with Funiculars, 1914

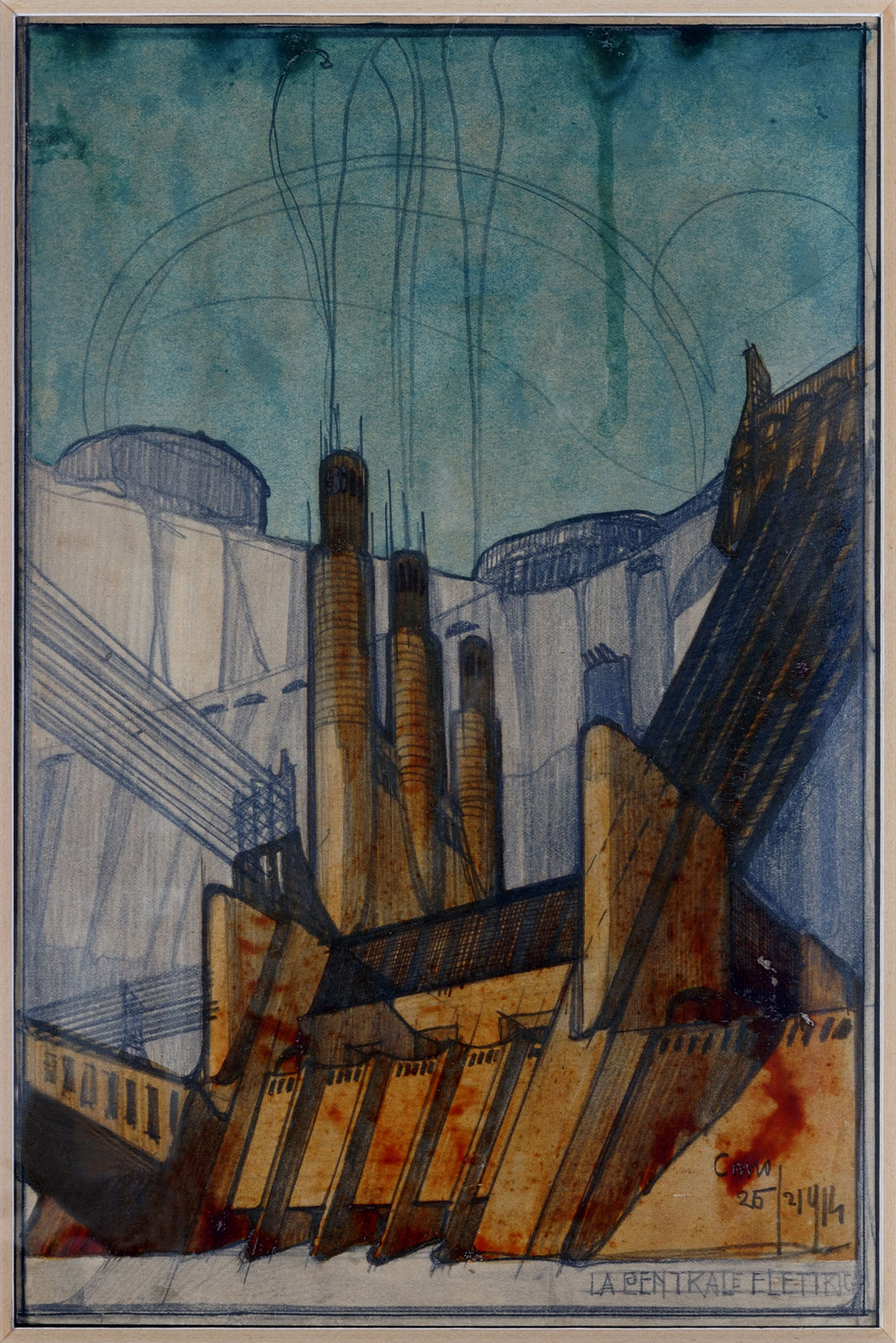

Sant’Elia envisioned a highly industrialized and mechanized utopian city of the future. He depicted a vast, multi-level, interconnected and integrated urban society. He worked on his designs for “Città Nuova, 1914” (New City, 1914) for many years, exploring new materials and industrial methods and imagining systems that would alleviate the need for internal load-bearing structure. His designs feature tall, narrow structures with thin, lightweight facades. External elevators and viaducts are prominent; he spoke of buildings that sat above and below ground by many stories.

The Futurist fixation with speed was satisfied by transportation systems for both air and rail travel, which were unimpeded and elevated. Sant’Elias’ influential designs featured vast monolithic skyscrapers with terraces, bridges and aerial walkways. They embodied the excitement of modern architecture and technology of the time and far beyond.

However, these early forays into new architecture stressed rhetoric rather than execution, and beautiful pictorial imaginings took precedence over specifics. Sant’Elia recorded no fundamental understanding or development as to how such modern structures could be implemented. When Sant’Elia died in the first world war and Chiattone moved in another direction, their Futurist designs were never further developed or ever built.

The New City — House Stairs with External Lifts, 1914

Despite his early demise Sant’Elias’ work is as much an influence on modern architecture as any. He is widely considered one of the finest draughtsmen in the history of architecture and the collection of his remaining drawings is extensive. They are highly regarded and incredibly detailed. In keeping with the notion of movement and speed, Antonio’s drawings were overflowing with dynamism and pace.

Straight lines and obscure angles emphasize the immense proposed height of his creations; each idea is centered around man and machine living symbiotically. People do not feature in his drawings, so there is little sense of scale or an imagined society. However, the pen and pencil strokes he used in many of the designs provide a feeling of activity and existence and feel somewhat familiar to the modern-day society we see today.

Futurist architecture was characterized by the notion of movement and flow, with sharp edges, strange angles, triangles and domes all illustrated in crisp linear detail. Sant’Elia and The Futurists’ designs hugely influenced technocrats and urban planners throughout the twentieth century. Prominent designers like Le Corbusier took inspiration from Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova with his unrealized Ville Radieuse (“Radiant City”). Like Città Nuova, Ville Radieuse was characterized by central planning, ease of transport and strict organization of its inhabitants. Looking to his drawings, many artists and designers were inspired to create the world we know today.

The Power Plant, 1914

While The Futurist movement fell by the wayside, in part due to its links to Fascism and Mussolini, to this day, the urban landscapes we are developing seem to align with the vision of Marinetti, Sant’Elia, Chiattone and the other Futurists. While our contemporary cities may not be as technologically advanced as the metropolis-machines of Sant’Elia’s concept, our self-driving cars, unlimited connectivity and boundless smartphones are more than even he could have imagined. Aesthetically, we may be slightly off track but it’s clear to see that the city of the future is here.

Feast your eyes on the world's most outstanding architectural photographs, videos, visualizations, drawing and models: Introducing the winners of Architizer's inaugural Vision Awards. Sign up to receive future program updates >